"I wanted to go to Korea and serve in a line company. This desire was not based upon grand heroic visions. World War II ended two days after my sixteenth birthday and I felt deprived of being able to serve in that war. My real interest was to determine if I had whatever it took to be a combat Marine."

- Perry J. Dickey

[The following memoir of his Korean War experiences was sent to the KWE by Perry Dickey in October 2010. A member of Dog Seven Marines while serving in Korea, Perry was born on August 5, 1929, and grew up at Denver, Colorado, where he attended and graduated from East High School in 1947. He married his wife Ila in 1953 and graduated from Denver University in 1956 with a Bachelor of Science in Law degree and a Juris Doctor degree. He was employed by Phillips Petroleum Company and lived in Houston and Amarillo, Texas before being transferred to Bartlesville, Oklahoma in 1963.]

Following is my memory of events during the time that I served with Dog Company, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division in Korea December 1950 through November 1951.

Following is my memory of events during the time that I served with Dog Company, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division in Korea December 1950 through November 1951.

Late in November or early in December of 1950, the Third Replacement Draft for the First Marine Division in Korea departed San Diego, California, onboard the troop ship USS General E. T. Collins. I was one of the Marines in that draft.

First, I should state how I came to be in the Third Replacement Draft. It started in February 1948 when I enlisted for two years in a Marine Reserve aviation squadron. This was a great experience as we worked on the Corsairs and were able to fly as passengers in various military aircraft and receive flight pay for the privilege. I reenlisted for another two years and in the spring of 1950 a new Marine Reserve artillery unit was organized and I transferred into the new unit, primarily to learn and have new experiences. There were only a few weekend training sessions before the outbreak of the Korean War and the unit was activated in July 1950 and sent to Camp Pendleton, California. Earlier I had signed up for four years with the Regular Marines, passed the physical and had a few days before being sworn in when the Reserve unit was activated. I elected to go with the remaining two-year reserve commitment rather than four years in the Regular Marine Corps.

When we arrived at Camp Pendleton, others were promptly assigned to various units and duties, but I was not. I was a Corporal that had not been to Boot Camp. Privates and PFCs were sent to Boot Camp, but Corporals were not. My offer of a reduction in rank was declined. I reported to a Gunnery Sergeant that was in charge of the S-2 or Intelligence Section. It was obvious that I was not being assigned due to indecision of higher authority. I pressed the Gunny for an assignment and his reply was that he was saving me for the BIG WAR that he anticipated with Russia. One day two 1st Lieutenants requested that I take a walk with them along the road. As we walked, they asked about my view of going to a prep school and if I did well I would receive an appointment to the US Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland. The discussion ended when I replied that the opportunity should be given to another Marine that intended to be a career Marine and that I wanted to go to Korea and serve in a line company.

This desire was not based upon grand heroic visions. World War II ended two days after my sixteenth birthday and I felt deprived of being able to serve in that war. My real interest was to determine if I had whatever it took to be a combat Marine. Thus I was back in limbo when an order was posted that any Marine could volunteer for immediate transfer to combat training. I was the first one to step forward and I was promptly on the way to tent camp, combat training and Korea. Soon I would have some good reasons to question the wisdom of my decisions.

The voyage from San Diego to Kobe, Japan, took about three weeks. There was little to do aboard a crowded troop ship, except there was ample time to contemplate the future. During this time, I gave more thought to the fact that Marines in line companies are directly engaged with the enemy and that many are killed. The ship operated under wartime orders and was blacked out at night. Radio reports of battles and intelligence were posted each day and the reports were quite grim. The Chinese had massed on the border and had entered into Korea with overwhelming force. These reports contributed to my developing fatalistic view that I could not control events and that I would probably be killed in Korea.

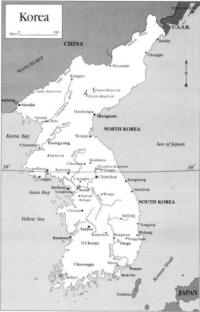

Initially the ship was bound for Japan where it would be unloaded and then the winter gear and other equipment would be issued to individual Marines. We went on board with combat packs and rifles, but we were not equipped for the extreme cold weather of Korea. The First Marine Division urgently needed replacements and there was a great effort to find a way for us to be landed in Korea and sent to aid the beleaguered Marines at the Chosin Reservoir. This could not be done as the ship was not combat loaded to issue needed equipment to individual Marines before leaving the ship. Thus, we went on to Kobe, Japan, where the ship was unloaded, equipment issued, and then we boarded another ship bound for Pusan, Korea. After arriving at Pusan, we traveled by train, with all of the windows shot out, to Masan, Korea, where we joined what was left of the First Marine Division at the Bean Patch.

It was dusk when we arrived at Masan. I was assigned to Dog Company, Second Battalion, Seventh Marine Regiment, First Marine Division where I served as a fire team leader, squad leader and Company or intelligence scout from December 17, 1950 through November 27, 1951. We were loaded onto six-by trucks to be transported to the Bean Patch.

Each Marine had his back pack and rifle and the trucks were fully loaded. I was on the outer edge of the truck bed with my pack hanging over the side. There was room in the truck bed for all of our feet, but our packs caused the top to balloon out over the side of the truck. My body with the pack extended beyond the truck bed and I was unable to retain any balance. The only thing that kept me from falling was some unknown Marine that grabbed my pack strap and held me in the truck. This was further complicated by the truck being driven over a rough and rutted roadway at high speed. I had some unkind words for the truck driver and the Marine Corps as I believed that my death in Korea should at least be due to enemy action.

| Roster Date | Total | Added | Dropped | WIA | KIA | Sick |

| December 16, 1950 | 47 | 8 | 196 | 19 | 12 | 7 |

Marines listed on the roster included wounded and sick Marines that were not present but were expected to return as fit for duty. The sick classification included Marines that had a serious illness or non-combat injury requiring hospitalization. Less serious illness and injuries were treated by U.S. Navy Corpsmen that were attached to the unit.

On December 17, 1950, I arrived with the 3rd replacement draft and joined the men remaining in Dog Company who were fit for duty. At that time, there were only a few Marines listed on the roster, as the Company was regrouping after the battle at Chosin reservoir and only seven men were fit for duty. It was reported that there were eight survivors, but one of them had severe frost bite on both feet and was evacuated for treatment. A Marine line company usually has 180 to 240 men and the few men remaining in Dog Company reinforced my view that I probably would not survive. Thus, I established a goal or objective that I hoped was within my control. That was to be a good Marine and to die with honor if that was to be my fate.

A tent camp was established at Masan and was known as the “Bean Patch.” In the beginning all of the enlisted Marines of Dog Company were assigned to one large rectangular tent. The ground was mud but there was straw on the ground inside of the tent where we had our sleeping bags. Our ranks increased as Marines returned from hospitals, along with more tents that were smaller pyramid type squad tents.

Christmas was celebrated at the “Bean Patch” with a turkey dinner that I did not enjoy and do not remember as I was ill with a bad case of flu. I continued with daily training exercises and did not seek medical attention as I had no intention of complaining of illness in the midst of returning Marines that had been wounded in action.

At the end of December 1950 the Dog Company roster increased due to Marines returning from hospitals as follows:

| Roster Date | Total | Added | Dropped | WIA | KIA | Sick |

| December 31, 1950 | 205 | 163 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

More Marines were added to the Dog Company ranks from the 4th Replacement draft that arrived on January 12, 1951, and the company was considered as combat ready.

Awarded Korean Campaign Battle Star-Communist China Aggression, November 3, 1950-January 24, 1951

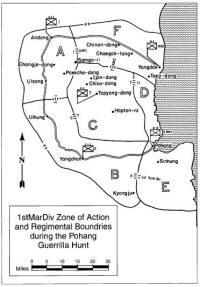

From January 17, 1951 through February 20, 1951, Dog Company participated in the Great Pohang Guerrilla Hunt. The 1st Marine Division routed guerrilla forces in the Masan-Pohang area. Operations continued around Masan into February. The last major engagement was fought at Uisong. The North Korean 10th Division was reduced in strength by 60%.

Following is a part of a letter written on January 24, 1951, by Sgt. Robert V. Damon (killed in action on April 10, 1951) from Pohang, Korea:

We made the trip up from Masan by truck. Very cold, but not intolerable. We pitched pyramid tents in mud fields on a hill above the harbor and airport. The next day we had working parties shoveling gravel and Friday we moved to another tent—wet and muddy on the floor. Saturday we dug foxholes to protect against air attack—holes 3 feet long, 2 feet wide, 2 feet deep and pile the dirt 1 foot high. Monday they said dig them 2 to 3 feet deeper. This week the battalion goes north west from here to look for gooks. There are a lot of them in the area 20-30 miles away. Our present camp site is no worse than Masan. Our floors are still damp mud about 1/3 of the men sleep on the ground—no cots. One of my men had yellow jaundice last week and was evacuated to Pusan or Japan to determine the cause. Two weeks ago I lost one to Pneumonia. Cramped guts has another—no duty today, I’m laid up. … It seems quite definite now that the men who came over last August (what’s left of them) will be going home very shortly—six months rotation.

Conditions and activity during this period are illustrated by part of another letter written on February 1, 1951 by Sergeant Damon:

Feb. 1 - "This is the first chance I’ve had to write in almost a week. Friday (1/26/51) we took off for the hills to hunt Gooks and we’ve been running up and down hills with heavy packs ever since. For 3 or 4 nights I averaged 2 hours sleep per night. The only gook I’ve seen so far was dead and half buried. Right now our platoon is lying on the South slope of a saddle. Some company is on the other side in a fire fight with the gooks. It appears that we’ve caught up with some at last. Every few minutes a bullet sizzes overhead or beside my head. Airplanes strafe and rocket the area. Four jets just going overhead now with long vapor trails behind. Artillery shell just whispered over and landed. The sun is warm. Grass we’re lying in very long and ground wet with snow here and there. The elevation about 900-1000 feet. Machine guns and rifles keep up a lively pace. These people we’re chasing appear to be guerrillas or bandits not too well armed. It’s hard to nail them because this country has very poor road net. The last week or two chow was inferior according to Medics. Since on this patrol we’ve had an average of 2 meals per day or 2 ½. This morning we had to shove off without eating. I had coffee, a little piece of candy, about 2 tbsp of sugar and a little cherry jam. When we’ll eat I don’t know. Supplies we either brought into this valley (town of Tuma-ri Northwest of Pohang and Northeast of Taegu) or brought in by helicopter. Later—stand by to move out. Flank patrol that went out about 300 yards just came back. Just got to the ridgeline a few minutes ago. Air strike going on. A mortar shell landed 30 feet from me but no one hurt. Firing just up ahead and Corsairs are strafing, bombing and rocketing. …Moved up higher and people with field glasses and scopes spot gooks being driven across our front by the Corsairs. I saw one only, several shots fired at him, no damage?? And we sit and wait for whom we shall soon see. The view from here is beautiful. So many trails over saddles and along peaks. Terraced fields or rice paddies everywhere.

Feb 4 - Sunday went down the hill due west thru thick brush and snow as much as knee deep up a mountain side and by 20:00 at the place to dig in for the night. Chow issued to be eaten after digging. While getting squared away to dig in, gooks firing on us with Russian sub machine guns and .30 cal light machine guns (U.S.) We finally ate after digging thru frozen soil—first meal in 24 hours. A very hard pull. I lost 2 men from exhaustion and one from injured eye going thru brush. Night was quiet but close artillery and mortar support put a fragment thru one man’s sleeping bag. On the next day, Feb 2, took it easy making coffee with snow and then in late afternoon went back down part way and up another hill side and dug in about 6 inches of snow. Up before daylight of Feb 3 and marched back to Tuma-ri in 2 hours. Had 2 hours for chow and then down to Battalion. Was on road 4 more hours.

At this time, we were engaged against guerrilla forces with a few small fire fights and only one casualty. My fear was great when first ordered to man a listening post for a two-hour watch during the night, as moving in and out of Marine lines in the dark was hazardous with or without activity by the enemy. This first occasion was aborted as we moved out during the night before I was scheduled to man the post. Later on I would often man listening posts with my fire team, but we always went out before dark and returned after dawn, which eliminated the potential hazard of a fruitless death by friendly fire. Our routine was to establish our position, dig in, zero in the 60mm mortars, rig hand grenades with communication wire, and proceed to wait, watch and listen.

The main memorable event for me during the Guerrilla Hunt period was my fire team was ordered to locate the enemy during the night, snatch prisoners, and return with the prisoners alive for interrogation. My fire team members were PFC Anthony Fernandez, PFC Gus Felt and PFC Bill Fish. Also present were Sergeant Mullen and a Korean interpreter. We went out on a bright moonlit night, moving through rice paddies, and waited in a rice paddy along a road. Soon we sighted a man coming from the direction of the enemy and I went forward to a point of cover at the road and captured the man when he came within reach. He had a Thompson machine gun, but did not offer much resistance. I took the prisoner about thirty yards to the position of my fire team and then there was more activity on the road. After a short time we determined Marines from the First Marine Regiment were on a combat patrol and we identified ourselves. At this time a major fire fight erupted, as the prisoner was a scout leading a Korean force that deployed when we captured him. My fire team was in the middle of a fire fight with two major forces, but we managed to return to the Dog Company Command Post with the prisoner.

We were exhausted from climbing hills and 50% watches at the end of the Guerrilla Hunt, but there was slight enemy activity. PFC Robert Ehrenfried was the only casualty wounded in action on January 31, 1951 and not included in the following roster:

| Roster Date | Total | Added | Dropped | WIA | KIA | Sick |

| January 31, 1951 | 231 | 76 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

This activity was reported by a letter written at Pohang, Korea on February 15, 1951 by Sergeant Damon.

Our last patrol was 15-20 miles, all night, up two mountains, feet wet in crossing streams and no gooks. The weather was so cold the waterfalls were frozen, at times we slept on wet snow and rain but most weather clear and all I could think about was food. One long all day march without food 24 hours…We have to go north again soon …On this last 18 day patrol my company didn’t lose anyone to enemy action (chasing gorillas), but the company next to us had 26 casualties including 4 KIA. My company did have a number drop out for various reasons. I lost temporarily or otherwise, all three of my corporals and two of my PFCs and I still kept going. Some had previous records of frost bite or jungle rot on the feet.

Awarded Korean Campaign Battle Star for First UN Counteroffensive, January 25-April 21, 1951.

On February 17, 1951, the 5th Replacement Draft arrived. From February 15, 1951 to March 12, 1951, Dog Company was engaged in Operation Killer in the Wonju area of Central Korea. Operation Killer was intended to drive the CCF north of the Han River. Five U.S. Divisions participated (1st Cavalry, 1st Marine Division, 2nd, 7th, 24th). U.S. casualties were 144 KIA and 921 WIA.

We marched north to participate in Operation Killer in cold and heavy rain, arriving at a river that we needed to cross as darkness fell. The crossing was delayed until the following morning. There were several Korean houses that were not occupied and most of the Marines elected to take shelter in these houses for the night. I observed a grove of fir or pine trees nearby and I proceeded to prepare my own shelter for the night. I cut branches from the trees and piled them about three feet deep and three by six feet in area. This permitted me to be relatively dry and warm as I slept on top of the branches under the cover of my shelter half.

The following morning we approached the river crossing and found the river in flood stage with a roaring current. There were amphibious trucks (DUKS) available to ferry us across the river. However, the DUKS were of no use as they were unable to navigate against the force of the current. No problem. We abandoned the DUKS and waded across the river, dodging large rocks that were being swept downstream. I believe that the river was successfully crossed without casualties except for the DUKS.

The weather at this time was bad, with rain in low areas and snow at higher elevations, along with wind. It was difficult to climb the steep and rocky ridges that were covered with snow and ice. The valleys were muddy with melting snow that blocked transport of needed supplies. Most supplies of ammo and rations were dropped from aircraft.

| Roster Date | Total | Added | Dropped | WIA | KIA* | Sick |

| 2/28/51 | 230 | 45 | 46 | 1 | 0 | 16 |

On 3/1/51 Dog Company moved north and attacked Hill 536 as part of Phase II Operation Killer.

Casualties from March 1 through March 6 were as follows:

| March 1, 1951 | WIA | PFC John W. Learned |

| March 1, 1951 | WIA | PFC Ralph H. Eby |

| March 1, 1951 | WIA | PFC Merle L. Davis |

| March 1, 1951 | WIA | PFC William T. Green |

| March 1, 1951 | WIA | PFC James E. Pierce |

| March 1, 1951 | WIA | PFC Allen W. Graves |

| March 1, 1951 | WIA | PVT Don A. McNeil |

| March 1, 1951 | WIA | PFC Thomas L. Kerns |

| March 1, 1951 | WIA | PFC William J. Barnett |

| March 2, 1951 | KIA | PFC Frank V. Riviello |

| March 2, 1951 | KIA | SGT John F. Dewitt |

| March 2, 1951 | KIA | PFC William D. Hoile |

| March 2, 1951 | KIA | PFC John G. Druzianich |

| March 2, 1951 | KIA | CPL Ralph R. Fisher |

| March 2, 1951 | KIA | HM3 Edward A. Lenoi |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Kenneth W. Gedris |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | CPL Ronald A. Meteviers |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Donald T. Sheldon |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Bob E. Duke |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | MSGT George H. Butler |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Edward A. Erickson |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Richard A. Evans |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Joseph C. Negri |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | CPL John J. Flynn |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC George A. Crawford |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC John T. Pickett |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC William K. Mortimer |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | SGT Joseph K. Hendricks |

| March 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Robert E. Bouchard |

| March 3, 1951 | WIA | CPL Alfred P. Schmitt |

| March 4, 1951 | WIA | CPL William Schaffhouser |

| March 5, 1951 | WIA | PFC Ronald F. Speechley |

| March 5, 1951 | WIA | PFC Joseph E. Henry |

| March 6, 1951 | 6th Replacement Draft Arrived | |

| March 6, 1951 | WIA | SGT Norman O. Williams |

| March 6, 1951 | WIA | PFC William J. Fish |

In the early part of March, we were the first U.S. forces to reenter an area known as Massacre Valley. U.S. Army infantry and artillery units had been overrun about three weeks earlier leaving artillery pieces, burned out trucks and about 700 bodies of U.S. Army soldiers lying as they had fallen. We passed through another area where U.S. Army troops had been massacred during May of 1951. These two events are merged in my memory; however, I remember passing through a valley with burnt U.S. Army vehicles, some of them still occupied with the bodies of U.S. Army soldiers. There was one six-by truck with about six bodies. One body was on the bench seat inside the truck in a natural seated position, but the body was reduced to charcoal. It was a warm day but there was no odor of decay or any other indication of the passage of time. There was nothing for us to do so we moved out and did not linger to inspect bodies or equipment.

There is a factual report titled "Massacre at Hoengsong" by Gary Turbak and published in the February 2001 issue of the VFW magazine. It reported that the Communist forces launched a major offensive on February 11, 1951, resulting in the slaughter of 726 U.S. Army KIA. The 7th Marines re-entered the area north of Hoengsong on March 7, 1951 for the first time since the rout, finding the battle scene eerily preserved.

As spring approached we moved north with aggressive offensive action. It was a continuous process of taking hills, establishing a perimeter, patrolling and then moving on to another hill. Activity now became more intense with more extensive fire fights and mortar and artillery fire during the day and night, along with more casualties. We were deprived of adequate sleep and dozed at opportune moments. Also, unnecessary talking after dark was unwise as it could disclose our position. When moving out we maintained a ten-yard interval, which was not conductive to conversations.

Marines in Korea were equipped with M-26 Pershing tanks. These tanks were armed with a 90mm gun, two .30 caliber machine guns, and one .50 caliber machine gun. At one time we did a lot of patrolling with tanks. The only good thing about this duty was the tank engines produced a lot of heat that was appreciated during cold weather. Part of the time we rode on the tanks and enjoyed the ride and warmth. When the tanks were engaged, we were deployed around them in defensive positions, as the infantry was responsible for protecting the tanks that were intended to inflict damage to the enemy. Tanks drew enemy fire and the tank afforded some protection to the tank crew, but there was nothing to provide cover for the infantry. The 90mm gun on the tanks was very effective, extremely loud, and produced a shock wave that could be felt for quite a distance. I have read that the muzzle blast from the 90mm guns can knock a man down at a distance of 30 feet.

On one occasion, I was at the side of a tank that was stationed about ten feet from the side of one of the few buildings that remained standing. This was a taller building and had windows on the upper level. I was between the tank and the building and was caught in between with the shock wave reflecting from the building. Almost instantaneously, there was a shower of broken glass around me from the upper level windows.

Air strikes were always welcome and spectacular. This may reflect my prejudice and be overstated; however, I believe Air Force pilots remained at high altitudes, Navy pilots were better and Marine pilots were the best and great as they trimmed the tree tops in providing close ground support. One outstanding air strike occurred on 6 March 1951. PFC Fish was wounded that morning when a spent bullet penetrated his foot, leaving the bullet between his toes. Later that day we were pursuing the enemy in a ravine or small valley. The enemy was in a fortified position at the foot of a bluff with an overhanging rock ledge. We had advanced and were close (30-40 yards) to the fortification prior to the air strike. The air strike started with a few low-level strafing passes which were not effective. The Corsairs were low and close enough for us to believe we had eye contact with the pilots and feel the rushing air and prop wash as they went by. We made hand signals to the pilots, pointing to the fortification under the bluff. The pilots responded either to our signals or more probable to directions of the ground control officer. The Corsairs then came in treetop low at an angle, causing napalm and white phosphorous to penetrate the fortification under the bluff. White phosphorous plummeted about us and we felt enormous heat from the burning napalm reflecting off of the rock overhang. We gave thumbs up to the pilots as they roared by, and they responded.

From March 4, 1951 to April 4, 1951, Dog Company participated in Operation Ripper. The objective was to drive the Communists back to the 38th Parallel and retake Seoul. Seven U.S. divisions participated (1st Cavalry, 1st Marine, 2nd, 3rd, 7th, 24th, 25th). U.S. casualties were 566 killed in action and 3220 wounded in action.

Below is a map showing the location of the 1st Marine Division during operation Ripper.

On March 7, 1951, Dog Company attacked "Oumsan", one of the highest mountains in South Korea. On that and the immediately following days, our casualties were:

| March 7, 1951 | WIA | PFC Kenneth I. Priecel |

| March 8, 1951 | WIA | CPL William G. McCall |

| March 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Willie F. Spence |

| March 11, 1951 | KIA | PFC Harold M. Crow |

| March 11, 1951 | WIA | PFC Donald L. Hannah |

| March 11, 1951 | WIA | CPL Theodore B. Dufrain` |

| March 11, 1951 | WIA | PFC John H. Alseth |

| March 11, 1951 | WIA | PFC Walter J. Abel |

| March 11, 1951 | WIA | CPL Gilbert L. Olson |

| March 11, 1951 | WIA | PFC John P. Guilfoyle |

| March 11, 1951 | WIA | MSGT George H. Butler |

| March 12, 1951 | WIA | PFC Frank J. Garber |

| March 12, 1951 | WIA | PFC Herbert A. Vermilye |

| March 12, 1951 | WIA | PFC Henry B. Haina |

| March 12, 1951 | WIA | CPL Kent Z. Pedersen |

| March 12, 1951 | WIA | CPL Jack F. Larson |

| March 12, 1951 | WIA | CPL Hans G. Schultz |

| March 15, 1951 | WIA | 1stLT Melvin M. Green |

| March 15, 1951 | WIA | SGT George G. Dresch |

| March 15, 1951 | WIA | SGT Edward Mullen |

Following is a copy of a letter written by Sgt. Robert V. Damon from Hoengchon, Korea:

It’s raining. My shoulder is a little sore from firing. I’m getting squared away for sniping. I was issued an 03 rifle and a telescope for it so that maybe I can at least have a few chinks at 600 yards. It’s a fine rifle and I am having a good time with it. …In fact it might be better than on the afternoon of 1 March, we slowly crossed a field and climbed a mountain side (couldn’t go faster - too hard) whilst shooting all around us, 3 wounded one killed in the platoon. I’ve never had bullets come closer than that-they can’t and still miss. Then that night the Chinese tried to blow us off the ridge with mortar and artillery which landed all thru the platoon area. I lay in my foxhole and shivered because I was cold … Lots of ridge running and hill climbing … and on the 12th more marching and on the 15th, 3 separate mortar and artillery barrages-one shell hit the road 15 feet behind me.

| Roster Date | Total | Added | Dropped | WIA | KIA | Sick |

| March 31, 1951 | 256 | 88 | 62 | 56 | 8 | 36 |

From April 1 through April 17, 1951, Dog Company was included in orders to attack, seize and reinforce the Kansas Line southwest of Hwachon Reservoir. On April 2, 1951, PFC Charles Strunk was wounded in action. Two days later, on April 4, 1951, Operation Dauntless began and Dog Company was ordered to cross the 38th parallel. Dog Company led the attack on April 5, the same day the 7th Replacement Draft arrived.

| April 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Charles Strunk |

| April 4, 1951 | KIA | PFC Charles L. Whatley |

| April 5, 1951 | KIA | HM3 Richard D. Dewert (Medal of Honor recipient) |

| April 5, 1951 | KIA | CPL Donald D. Sly |

| April 5, 1951 | KIA | PFC Anthony J. Falatcach |

| April 5, 1951 | KIA | PVT Richard W. Durham |

| April 5, 1951 | WIA | PFC John A. Hokanson |

| April 5, 1951 | WIA | PFC Manuel C. Mares |

| April 5, 1951 | WIA | PFC Warren J. Gerweck |

| April 5, 1951 | WIA | PFC Everett L. Fales |

| April 6, 1951 | WIA | TSGT Francis R. Perry |

| April 6, 1951 | WIA | PFC Keith F. Ester |

| April 7, 1951 | WIA | PFC Albert F. Stauder |

| April 10, 1951 | KIA | SGT Robert V. Damon |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Dean C. Phillips |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Lafayette Flanne |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Alex J. Garcia |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Clarence A. Dehne |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Ben A. Martinez |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Warren C. Funk |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Donald L. Berg |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC James P. Davis |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Kenneth Ellis |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Harold I. Curry |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | CPL Myles M. Anundson |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | CPL Donald W. Lang |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | 1stLT Richard Humphreys |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Ed M. Dozier |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Lawrence E. Davison |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Jose J. Flores |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Samuel Gejikian |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | CPL Holbrook M. Bunting |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Merle L. Davis |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | CPL John J. Flynn |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | MSGT George H. Butler |

| April 10, 1951 | WIA | SGT Edward Mullen |

Below is an Arial photograph & map of the area that I have marked to show where Sgt. Robert V. Damon was KIA on 4/10/51.

On April 10, 1950 Dog Company was on what I believed to be a combat patrol to locate and engage the enemy and to establish a major point of resistance rather than a rear guard action to delay our advance. We had made contact and were receiving small arm and machine gun fire from our right. Rounds were cracking in all directions and one round ricocheted off a small tree branch in front of my head, showering my face and eyes with bark and debris. It then struck the man to my right, PFC Jose Flores, in the face. At that time Sgt. Robert Damon came to my left and tapped me on the shoulder, indicating for me to follow him.

Sergeant Damon and I started moving to our left and up the hill toward the enemy. We progressed forward about a hundred or more yards and I think out of sight of other company members. I was several yards behind Sergeant Damon when he shouted, "Shoot em!!" Sergeant Damon had an .03 Springfield sniper rifle with a scope mounted over the receiver. The rifle could hold six rounds, but each round had to be loaded separately into the magazine and he wanted to withhold firing his rifle. Sergeant Damon had spotted a rifle barrel in the bushes about two yards in front of him and yelled, “Shoot em!” I also saw the rifle, and fired into the bush. At this time another enemy with his rifle aimed at me appeared about ten feet in front of me, but slightly to the right side. I fired at him, but my M-1 rifle went "click" and did not fire. Instantly I started dropping to the ground and used my left hand to slide the bolt back to clear and load another round into my rifle. I fired again with the rifle at my hip and in a crouched position. I was fortunate to hit the enemy with a shot between his eyes that blew out the top of his head.

Now hand grenades started to fall and explode all around me. I made a dive for cover as there was a tree uphill and a small rock protruding from the ground. When I hit the ground, I saw three hand grenades tied together and just beyond my reach a few feet uphill and to the right side of my head. I turned my head away from the grenades as they exploded. I was surprised at being alive after the grenades exploded. I looked to my left and saw Sergeant Damon standing on top of a bunker, firing a .38 revolver into the entrance. He fired several rounds and then I think there was more than one shot, possibly a volley, from the bunker. Sergeant Damon was fatally shot in the chest at a range of a few feet. The revolver rotated on his trigger finger and dropped into the bunker. He staggered a step or two toward me and fell face down with his head downhill. There was a tree stump about a foot high and Sergeant Damon fell with his chest on the stump, an arm on each side and with his head drooping, but not touching, the ground. He uttered a small gasp, a large volume of blood gushed from his mouth, and he was dead.

Sergeant Damon's body was about six feet from me and between me and the bunker entrance, which was about ten feet away. I was in a blind spot for the bunker and not within the line of fire. The enemy apparently let Sergeant Damon and me progress without firing to avoid giving away their position. I had two hand grenades. I missed with the first grenade by throwing it over and past the bunker entrance. The second grenade went right into the entrance, but was promptly thrown back at me and exploded downhill. My position was known to the enemy within the bunker, but they were afraid to stand up and fire at me. They did hold a rifle up on the outside of the entrance and fire blindly in my direction. I returned fire, attempting to hit the exposed hands and arms. The malfunction of my rifle now became a benefit, as it did not eject the clip after firing the last round and I was able to quietly reload.

I did not intend to storm the bunker with my single fire rifle, but I held the enemy off and contemplated possible action. My concern was that the company was on a combat patrol and probably would withdraw after establishing the main line of resistance. I thought Sergeant Damon and I might not be missed until after the company had withdrawn. Sergeant Damon and I had gone forward in the heat of combat without notice to others. I was determined not to be taken prisoner, and I believed the best course of action was to hold out until dark and try to return to the company position.

After an unknown period of time, I looked downhill and saw a face staring up at me. It was Pvt. Raymond McCallum, who was a replacement that joined our unit a few days earlier. McCallum had been concerned about his conduct when first exposed to combat and I had advised him to follow me, do what he had been trained to do, and that he would be okay. McCallum complied with that advice and now was in the line of fire of the bunker about fifty yards downhill. I motioned for him to withdraw and return with help. He understood and disappeared. Some time later PFC Gus Felt came inching up from below and to my right. Gus had grenades and was better than I in using them. Gus pulled the pin, let the spoon fly, held the grenade with a grin as I squirmed, and then threw the grenade--which went into the bunker entrance and exploded immediately.

Gus and I continued up the hill where we encountered more enemy who were in disarray. Gus and I proceeded to fire at will upon the enemy who were about one hundred yards away and not returning fire. It was more like target practice than combat. Gradually other men arrived and after some time we withdrew and started down the hill. Sergeant Damon's body was removed before I returned to the location. I did help another wounded Marine from our platoon down the hill. He was a squad leader and I do not remember his name. His left leg was injured and he was unable to walk. After getting him down the hill, I kept his rifle and destroyed my defective one. At that time I became the squad leader to replace Sergeant Damon, who was posthumously awarded with a Silver Star and Purple Heart.

As noted above, Gus demonstrated the wisdom of holding a grenade and timing it to detonate upon arrival at the target. I never threw another grenade by simply pulling the pin and throwing the grenade. The procedure is to pull the pin, let the spoon fly, hold the grenade for the appropriate time and then throw the grenade, thus avoiding undesirable returns.

Below is a copy of a magazine article based upon the action on April 10, 1951, that was written by Jim McGivern, as told to Dewey Linze, and published in the December 1952 (Volume 1, No. 9) issue of Men magazine that is no longer in publication. The publisher of the magazine was Martin Goodman; editor, Noah Sarlat; associate editors K.T. Meyer, V.A. Jirsa, and N.R. Sachs; and art director Mel Blum. Men magazine was published monthly by Zenith Publishing Corporation, whose offices were at 270 Park Avenue in New York City. The "Ridge that Drank Blood" was a "fictionalized" article about a true event of the Korean War in which Dog Company Marines participated. It read as follows:

Black clouds, bloated with rain, hung menacingly above the “Kansas Line.” It was the morning of April 10, 1951, and up ahead Hill 491, a shell-gouged mound of dust, stood out ominously.

I was a Browning Automatic Rifleman with the 7th Marine Regiment, 2nd Battalion, Dog Company and Second Platoon. At 7 a.m., I jumped off Korea's central front with the First and Second Platoons, the Heavy Mortar Platoon and the Machine Gun Platoon of Dog Company. We were marching single column to contact the North Korean and Chinese Reds, who were dug in on Hill 491's crest.

"There it is," said John Fries, a tall gangling Marine, "that's the goddamned hill we're supposed to go up." I watched Fries' eyes narrow contemptuously at the hill ahead and its two parallel ridges which ran down to the hanks of the Pukan River. "Do you see it, Mac?" he asked, staring fixedly. "That's a hill that's soaked up more blood than a slaughterhouse sewer. You got to have guts to go up it, and then after you make it, you may get them shot out." "I guess that's the story about any of these damned hills," I said.

Fries was also a Browning Automatic Rifleman. Every BAR man at the front was proud at the individual eminence it gave him, even though his life expectancy during a fire fight was only 27 seconds. The BAR men stuck together and exchanged amities like a true brother-hood.

Besides Fries and I there was John Cebula. Cebula was from St. Joseph, Missouri. He came from an influential family and apparently had lived a cloistered life. But at the front he was a BAR man, and he shot and drank and cursed like one.

There was John "Fitty Smitty from New York City" Smith. A short kid, Smitty never went without his "Long John" underwear and two pairs of trousers. He was good-natured, and we always prodded him about New York and his relationships, or lack of, with the girls. But when it got hot up front, Smitty was right there, ready to split open the heart of an enemy with his hell-spitting BAR.

We finally arrived at the Pukan River, stopped and filled up our canteens and bellies. We checked our Browning Automatic Rifles and set them to fire. Lt. "Get Lost" O'Donnell came forward, cupped his hands around his mouth and yelled the orders of Capt. M. A. Mackin, the company commander, to us. "After we cross the river, the Second Platoon will take the ridge to the left," he said, "and the First Platoon will move up the ridge to the right. I don't want anyone goofing off. Keep up and maintain order. That's all. Let's shove off"'

We forded the river, and the tension expanded among the four Dog Company platoons. After we reached the opposite bank, the Machine Gun Platoon and the Heavy Mortar Platoon were given orders to halt their march at the foot of the ridges and provide cover fire for the two rifle platoons from some rice paddies.

"This is going to be a bitch," said Fries. "They're waiting up there like a flock of vultures." "Let them wait," Cebula said. "Let the bastards wait!" We neared the hill and orders came back for the two platoons to break up and head for the ridges, which were separated by a shallow ravine. The Machine Gun and Heavy Mortar Platoons had already taken their positions. "Here we go," I said. "We'll step into trouble at any second, flow." "You said it," muttered Smith, squinting his eyes at the hill's crest. "It won't be long."

We commenced our march up the ridge, cautiously watching for signs of the enemy. Nothing stirred about the landscape except the shell-shredded trees. Now and then the heel of a combat boot sent a rock skipping down the hillside, and the muttered curse of the Marine fighter carried through the silence that shrouded the ridge.

We’d reached the midsection of the ridge when the Reds opened fire on us. We hit the dirt. I looked around for Fries, but he was gone. I flopped behind a rock-pile and waited for the firing to cool. Small arms fire from the rifles, burp and machine guns snapped chips off the rocks near my head. "Now, what the hell are we going to do?" asked an ammo carrier near me. "Damned if I know," I said. "We'll have to stay here until they let up."

To the right of the Second Platoon the First Platoon moved up toward the middle of the ridge they were ordered to cover. High on the crest of Hill 491 a mortar coughed, and a shell screamed to earth and burst. It chopped off the leg of a Corpsman who had run to aid a Marine shot through the jaw. "Jesus Christ!" he yelled. “Will someone do something? My leg is shot off!” "Who the hell got hit?" inquired the ammo carrier. "That was Murphy," I said. "He got it bad."

Murphy kept shouting for help. "Rebel" Phillips ran from his cover to kneel beside the wounded Corpsman. He tore open the trousers of the Corpsman and glanced at the shell-shattered leg. "Someone come and help Murph," he called. Charlie Strunk, a gaunt-featured rifle-man, ran through the streaking fire from the hilltop. He dropped beside Phillips. "He don't look so good," said Phillips, with his Southern drawl. "He don't look so good, Charlie." Strunk ripped open Murphy's first aid kit and yanked out a morphine dose. He gave it to the Corpsman, and it quieted him. As Struk got up to leave, a rifle shell sawed across the fingers of his hand. "We'll get you out Murph," Phillips said. "Don't fret, boy. we'll get you out." They pressed close to the earth until the fire concentration left them; then they moved Murphy back.

A second mortar shell burst near me as I crawled uphill from behind the rock-pile cover. The detonation lifted me off the ground. I thought I had had it. I lay there until the air returned to my lungs. I raised my head and watched a pattern of machine gum shells zigzag through the dust yards ahead of me. The Reds were giving us the works. The machine gun shells picked up the dust and threw it into my face as they whizzed away inches from the barrel of my BAR. Then, the Red gunner apparently picked another target and left me alone.

As we continued the crawl up the hill, the First Platoon was stopped. Near the top of the ridge a Chinese hurled grenades from a bunker at the First Platoon Marines, keeping them pinned to the ground.

"Get that son-of-a-bitch in that bunker!" the word came over the walkie-talkie. "He's holding up the parade!" Sgt. Bob Moll, squad leader, called for the BAR men. Smith, Cebula and I raced through the Red fire. "We'll cover you!" he said. "Get up these and knock off that bastard!" We began the slow, tedious belly-crawl progress up the ridge. When we were parallel with the Red's bunker we stopped, slapped the BARs on "fast fire" and waited. When the Red raised to throw an-other grenade, we blasted him. He slumped down into the bunker and stayed there.

The First Platoon moved on up the ridge toward the crest of Hill 491. The Second Platoon sergeant, aiming a .03 sniper's rifle, got the drop on a Chinese with a burp gun. He fired a shot, and the rifle jammed. As the Red opened up with his burp gun from the waist, the sergeant got to his feet and charged him with a .38-caliber pistol. The Chinese shot him through the heart. A Marine rifleman, who followed behind the sergeant, shouldered his weapon and cracked the Red with a shot between the eyes.

As we reached the top of the hill, we discovered that some of the enemy had abandoned their weapons--Bren guns, machine guns, and "Long Tom" 31-caliber rifles--and fled. The firing became sporadic, but still very intense. "We made it," said Cebula. "Yeah," I said, "but there's going to be hell to pay if we stay up here long."

On the opposite side of Hill 491 were countless bunkers. They were occupied by the feigning Chinese and North Korean Reds. I watched the "Boy from Alabama," a kid named Morgan, carrying an M-1 rifle, mosey down the hill and jerk a belt of carbine ammo from a tree near an enemy bunker. "Anybody need any carbine ammo?" he asked, waving it jubilantly overhead. "Sure," someone said, "bring it on up!"

As Morgan turned to go, a Red walked out of the bunker, laughing and saying, "Hello! hello! hello!" Morgan dropped the belt of ammo and leveled his rifle at him. "Any more of you bastards in there?" he questioned dangerously, motioning at the bunker. The Red muttered something completely unintelligible to Morgan, and three other Chinese crawled from the bunker. Morgan brought them up the hill for G-2, the intelligence detail, to talk to.

Morgan then went back to the bunker and pitched a fragmentation grenade inside. A Red, rattled and shaken by the concussion, peeked from the hole, but ducked back when he spotted Morgan. The "Boy from Alabama" let go another grenade. The Red raised from the bunker again, and this time he was shot through the head. Near me a Chinese took two bullets just above the eyes from a BAR. The top of his head was lifted off, and his face was like a limp rubber mask. His brains were jerked out of his skull and spilled behind him.

After reaching the crest of the hill, we fanned out and gave cover to a temporary Command Post established for purposes of communication. I was some 20 yards away from the C.P. when a Communist with the world's most terrifying gun--the burp gun--jumped up from a shallow trench and swung the weapon towards me. I dumped a half a magazine into him, and he fell back into the trench.

I saw a young Marine rifleman get shot through the wrist, as he exchanged fire with a Chinese soldier. I emptied the BAR at the Chinese and swatted him down. The Marine's wrist was thin, and the shot almost severed his hand from his arm. But he waited calmly, quietly for the Corpsman to come and give him the morphine dose.

For several minutes I became separated from the other BAR men, who wandered around picking out targets. But finally I spotted Cebula and strode over near him. "We just about got this place mopped up," he said. "I hope so," I retorted. “1 don't like sticking around here too long. It's too hot!"

As we moved toward a shell splintered tree, a Chinese suddenly leaped up from cover, swinging his burp gun from his shoulder. "Get him!" I shouted. Cebula dropped the barrel of his BAR and pressed the trigger. The gun spit one shot and jammed. I lowered my BAR and gave the Red an entire magazine, fast fire, in the chest. Blood and guts flew for six feet. I slipped a new magazine back into the BAR and helped Cebula to remove the jam from his gun. "Hey, you guys!" yelled Smith. "Lt O'Donnell said the Captain's going to call in an air strike against the hill! We're moving back. Let's go!"

Both the First and Second Platoons left Hill 491 for the Kansas Line We had one Marine killed and 32 wounded. The Chinese Reds had 30 killed and an undisclosed number wounded. We also took four prisoners. And that's the story of Hill 491, the mound of dust that 'soaked up more blood than a slaughterhouse sewer.'

Although the preceding article was a fictionalized report of Dog Company activity on April 10, 1951, the names of the real Marines referred to in the article were listed on the roster of Dog Company as shown below:

| Name | Joined | WIA 1st | WIA 2nd | Dropped | Sick |

| Cebula, PFC John J. Jr. | 15-Mar-51 | 15-Oct-51 | 18-Dec-51 | ||

| Fries, PFC John | 15-Mar-51 | 11-Apr-51 | 24-Nov-51 | 26-Sep-51 | |

| McGivern, PFC James M. | 05-Apr-51 | 04-Jun-51 | |||

| Moll, CPL William R. | 18-Jan-51 | 18-Oct-51 | 25-Aug-51 | ||

| Morgan, PFC Marvin T. | 18-Jan-51 | 13-Sep-51 | 30-Sep-51 | ||

| Phillips, PFC Dean C. | 18-Jan-51 | 10-Apr-51 | 27-Apr-51 | 21-Aug-51 | |

| Smith, PVT John D. Jr. | 06-Mar-51 | 13-Sep-51 | |||

| Strunk, PFC Charles | 21-Aug-50 | 28-Nov-50 | 02-Apr-51 | 07-Dec-50 | 03-Nov-50 |

Awarded Korean Campaign Battle Star for Communist China Spring Offensive, April 23-July 8, 1951.

On April 23, 1951, PFC Vernon E. Firnstahl and PFC Robert F. Vetter were wounded in action. On April 25, 1951, PFC Jesus J. Guerra was WIA. The following day, on April 26, the 1st Marine Division was ordered to withdraw and fall back to a section of No Name Line at a location near Hongchon.

I knew more about Sergeant Damon and others who joined the company during December 1950 as we had an inactive period in reserve while the company was rebuilding. Replacements were added after we were engaged and there was a lot of turnover. Men came and went and we never really knew much about anyone. During the best of times we were on fifty percent watch when we were dug in. Two Marines dug in together and "fifty percent watch" meant that one was always awake. There was no allotted time for a watch, as each Marine remained awake and on watch as long as possible and then nudged his partner to take over the watch. The elapsed time for each watch may have been a few minutes or several hours. When it was dark and quiet on watch, there was time to think and I had three reoccurring fantasies that were beyond my expectations. One was a china plate in bright sunlight with one egg sunny side up. The second was an ordinary one-inch pipe sticking up out of the ground with a tap that could be opened to provide water whenever desired. The third was a pretty young lady, standing in an open doorway, and waiting just for me.

On one occasion, I received an assignment to man an outpost that I believed to be more exposed and vulnerable. At that time I was the squad leader and I assembled the squad and requested three volunteers to man the post with me. This was a stupid act, as no one volunteered; thus, I turned and proceeded toward the position. It was a great relief when I looked back and saw that PFC Anthony Fernandez, PFC George Golubosky and PFC Gus Felt were quietly moving out with me. This is an example of inexperience and failed leadership as I attempted to avoid selecting and ordering the men needed to do the job.

We ate cold (no fires) C-rations except when we were in reserve. Rations were distributed along with ammunition each day. Each Marine opened the ration carton, took what he wanted, and discarded the rest. Rations were consumed on an individual basis whenever possible or desired, much the same as drinking water from his canteen. At appropriate times, it was possible to quickly heat a small amount of water for coffee or hot chocolate. I usually had a small amount (less than 1/8th pound) of plastic explosive. This material was used by rolling a ball about the size of a marble and placing it under a C-ration can filled with water. I used a match to light the plastic explosive and watched it quickly flash and burn with no smoke. Some hand grenades could also be used to heat water by unscrewing the detonator and removing the explosive. However, some of the grenades had a yellow cake explosive that burned slow with black malodorous smoke.

One time when we were in reserve for a few days, we were treated to a hot meal of steak, eggs, milk and two bottles of beer. I enjoyed beer, but not as much as others--especially when the beer was hot. So I drank one beer and gave the other one to PFC Anthony Fernandez. This was more than fair as Tony did not smoke and kept me supplied with his cigarettes. Tony was the BAR man in my fire team and usually was near my side or behind me. It was Tony that told me about Italian Pizza Pie that he described as a hot and tasty meat pie. Tony assured me that I would like a pizza, but I was not convinced and it would be a long time before I discovered that Tony was correct. Tony is no longer alive and the last time that I saw him, we were stationed at Camp LeJeune in NC. In Korea, Tony had previously mentioned his fianc¼e and I asked how she was doing. Tony lived in Minnesota and it was cold during the winter when he returned home and went to see his girl. Tony intended to surprise her and went to her home without calling. As he arrived, she was leaving with a girl friend. When Tony embraced his girl and held her gloved hand, he noticed that his fianc¼e was not wearing his ring. Tony said nothing, but his girl went back into her house for a moment and returned wearing the ring for the last time as Tony's fiancee.

| Roster Date | Total | Added | Dropped | WIA | KIA | Sick |

| April 30, 1951 | 264 | 46 | 38 | 50 | 6 | 23 |

Casualties resulted from weather as well as combat. Late in the spring we were ordered to drop our packs and form a skirmish line. We went up the sunny side of a hill that was dry and clear to the ridge. We continued down the shady side that was covered with wet snow about knee deep, causing us to be quite wet when we reached the bottom. The sun was setting as we started to assault the next hill. We continued the assault and secured the hill about midnight. Staying warm was not a problem while we were active, but we cooled rapidly after digging in and waiting for a counter assault. We were cut off without access to the rear for our packs and supplies. The night was cold--below freezing, but above zero. Supporting artillery fire maintained our perimeter during the remainder of the night as we huddled together to maintain body temperature. I was fortunate to spend the night sitting with two other men, PFC Fernandez and PFC Golubosky, rotating the warmest middle position. Others were not as fortunate. Many men were not fit for duty the following morning and never returned.

On April 7, 1951, the 8th Replacement Draft arrived.

As the weather grew warmer in the spring, Tony and I decided to dispose of our sleeping bags that were dirty and smelly. We buried the bags in a hole. Soon we discovered that we were unwise, as nights were still cold. Tony and I approached a new replacement that arrived with a full pack and two blankets. We were standing on each side of the replacement and asked for one of his blankets. The replacement was fresh out of boot camp where he learned that Marines are responsible for their equipment and are never to be caught short. With great reluctance, the replacement surrendered a blanket that we cut so that Tony and I each had one half of the blanket. The replacement soon learned that everything is expendable in combat.

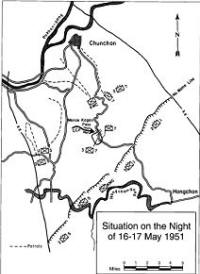

The CCF Second Spring Offensive took place from May 17 through 22, 1951. Four U.S. Divisions (1st Marine, 2nd, 3rd and 25th) participated. There were 333 killed in action and 888 wounded in action. Operation Mousetrap began on May 16, 1951.

This operation is covered in U.S. Marines in the Korean War at pages 393-394. The Morae Kagae Pass was located about midway on the road between Chunchon at the north and Hongchon at the south. No Name Line was the front line for UN forces and it was located midway between the pass and Hongchon. The 7th Marines were ordered to defend the pass, keep the road open, and be prepared to fight their way out and back to the main line if the Chinese attacked in force. The purpose was to guard the Morae Kagae Pass and to trap advancing Chinese forces. Korean Marines were located on the west side of the road about halfway between Chunchon and the Pass. 1st and 2nd Battalions of 7th Marines were located on the east side of the road. 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines were located on the west side of the road and on the south side of the Pass.

There was an intense battle for several hours as the Chinese forces were trapped. This was a successful operation with Chinese losses estimated to be 530 men, along with equipment. Marine losses were seven KIA and 19 WIA. The 7th Marines were withdrawn and returned to No Name Line. There are photographs of the aftermath that have been widely distributed showing the enemy lying as they fell in battle, as well as photographs of the mass burial.

My memory of Operation Mousetrap is limited to a few outstanding events. I do not recall where we were dug in during the night as related to the location of the main battle. Also, I do not recall any significant activity at our location; however, there may have been some activity that was more or less routine with mortar, artillery and sporadic small arms fire.

I do remember a bright and sunny morning when we left our position and advanced to the location of the main battle. It was obvious there had been a major fight, as there were many Chinese bodies along the way. The number of bodies increased as we advanced to the area that was the center of the activity. There were hundreds of bodies, some lying as they had fallen and others stacked awaiting burial. A Marine bulldozer was excavating a large trench for a mass burial. The dead Chinese were being carried and placed into the trench as the bulldozer continued to work increasing the size of the trench. I believe that Marines were handling the dead Chinese, with one Marine at the head and another Marine at the feet. Each dead Chinese was carried by two Marines and placed, not dragged, into the trench. I do not believe that Dog Company Marines were used for this burial detail.

I also remember that my squad was standing by waiting for orders to move out. The ground under my feet felt spongy and I used the toe of my foot to push and move some of the dirt. Much to my surprise, I found that I was standing on the forehead of a dead Chinese that had been buried in a very shallow grave. Apparently this dead Chinese had been buried during the battle.

We continued taking hill after hill, tank patrols, combat patrols and recognizance patrols. After taking a hill we dug in, secured the perimeter, carried dead and wounded down the hill, and returned with ammunition, C-rations and water. I acted more as a robot responding to commands, acting with instinct, without thought and void of emotion with the exception of dead Marines. I did not hate the enemy, abuse prisoners or enemy bodies. I was indifferent and unconcerned about the fate of anyone other than Marines. Our tongues were thick from dehydration as we had inadequate water for drinking and even less for hygiene. Often when we had water, it was frozen and unusable as we seldom had the luxury of a fire. During the entire time I was in Korea, I can remember only one shower. A tent was set up with hot water and we each had a few minutes for a shower. Occasionally when we were in a secure area with warm weather and we came upon a river, we would go into the river with our clothes on, wash or rinse the clothes, and then leave the clothes to dry on the river bank while we continued to wash and swim. Usually we moved out before the clothes were dry.

We carried only what we needed and discarded all surplus items. We started in the winter with cold weather gear and clothing. Items were left behind when damaged or as the weather became warmer. A lot of gear was left behind and later needed such as parkas, gloves, blankets and sleeping bags. But even when we had gloves, our hands were cold and rigid until warmed by warmer weather. I traveled light and my pack held a sleeping bag or part of a blanket, a shelter half, sometimes a poncho, an entrenching tool, some C-rations, and usually three bandoliers of ammo and three hand grenades. This was in addition to the ammo in my belt and grenades in my pockets. The shelter half was only used as a tent when we were in reserve. At other times, the shelter half was used for a ground cover or improvised shelter from rain or snow.

Operation Detonate was conducted from May 20, 1951 through June 8, 1951 with the objective to retake the Kansas Line. Seven U.S. Divisions participated (1st Cavalry, 1st Marines, 2nd, 3rd, 7th, 24th, 25th). There were 530 killed in action and 3195 wounded in action. Dog Company jumped off in the attack drive back north on May 23, 1951. Its first casualty was the next day. The casualties from May 24 through the end of the month were as follows:

| May 24, 1951 | WIA | PVT Donald R. Hanlon |

| May 27, 1951 | KIA | PFC Angelo M. Velasquez |

| May 27, 1951 | KIA | PFC Carlos Hermosillo |

| May 27, 1951 | WIA | PFC Bobbie G. McKee |

| May 27, 1951 | WIA | PFC Arthur L. Contreras |

| May 27, 1951 | WIA | CPL Donald R. Comisky |

| May 27, 1951 | WIA | PFC Jack J. Lawrance |

| May 28, 1951 | WIA | PFC Herbert L. Holiday |

| May 28, 1951 | WIA | PVT Robert D. Gappa |

| May 28, 1951 | WIA | SSGT Joseph F. Alston |

| May 29, 1951 | WIA | SGT Herman R. Lawrence |

| May 29, 1951 | WIA | CPL Thomas F. Johnson |

| May 29, 1951 | WIA | PVT Alfred M. Trefney |

| May 29, 1951 | WIA | MSGT William H. Trefney |

| May 29, 1951 | WIA | PFC Herbert H. Stelzer |

| May 29, 1951 | WIA | TSGT Francis R. Perry |

| May 29, 1951 | WIA | PFC Vernon E. Firnstahl |

| May 29, 1951 | WIA | 1LT Richard Humphreys |

| May 30, 1951 | WIA | PFC Richard A. Moore |

| May 30, 1951 | WIA | SGT James G. Cotton |

| May 31, 1951 | WIA | PFC General G. Holliday |

| May 31, 1951 | WIA | PFC Louis M. Pena |

| May 31, 1951 | WIA | PFC Carroll F. Fugate |

| Roster Date | Total | Added | Dropped | WIA | KIA | Sick |

| May 31, 1951 | 240 | 11 | 35 | 20 | 2 | 12 |

During June and July 1951 Dog Company continue to march north, advancing into the Punchbowl area of eastern North Korea. Casualties continued to mount, before and after the 9th Replacement Draft arrived on June 6, 1951.

| June 1, 1951 | WIA | PFC Johny A. Martinez |

| June 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Walter E. Towns |

| June 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Arthur A. Trevino |

| June 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Matthew Gilmartin |

| June 2, 1951 | WIA | PFC Franklin J. Marino |

| June 6, 1951 | WIA | PFC Byron D. McClure |

| June 7, 1951 | WIA | PFC Victor S. Geib |

| June 8, 1951 | WIA | PFC Carroll B. Bagley |

| June 8, 1951 | WIA | PFC Earl L. Touchstone |

The 1st Marine Division encountered heavy North Korean People's Army (NKPA) resistance during the Battle for the Punchbowl June 10-16, 1951. There were 67 Marines KIA and 1044 WIA. Dog Company had the following casualties from June 10 through June 30, 1951:

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Ward Schupbach |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Edward Garr |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | CPL Stuart W. Culp |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Herbert R. Kent |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | 2LT Lealon C. Wimpee |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Ernest R. McLain |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Max L. Dix |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Derek C. Jacobs |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC George M. Kapuniai |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | CPL John W. Angle |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Louis M. Hickman |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Kenneth Standridge |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | SGT Roy J. Jones |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | 1LT Thomas W. Burke |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Robert L. Vest |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Edwin V. Tremaine |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Maurice M. Sutton |

| June 10, 1951 | WIA | PFC Warren J. Gerweck |

| June 11, 1951 | KIA | SSGT Albert H. Dunlap |

| June 11, 1951 | WIA | CPL Charles E. Straub |

| June 11, 1951 | WIA | PFC Eugene A. Bruno |

| June 11, 1951 | WIA | CPL Donald W. Lang |

| June 11, 1951 | WIA | TSGT Francis R. Perry |

| June 13, 1951 | WIA | PFC Edward D. Lane |

| June 13, 1951 | WIA | PFC Richard O. Miller |

| June 13, 1951 | WIA | PVT Frederick Frankville |

| June 17, 1951 | KIA | PFC Bernard C. Jonas |

| June 17, 1951 | WIA | PFC John E. Duck |

| June 17, 1951 | WIA | PFC Dennis A. Hunt |

| June 17, 1951 | WIA | SSGT Donald H. Mahoney |

| June 17, 1951 | WIA | 1LT Earl B. Musser |

| June 17, 1951 | WIA | PFC Curtis L. Mason |

| June 17, 1951 | WIA | PFC Joseph J. Miller |

| June 17, 1951 | WIA | PFC Charles W. Curley |

| June 30, 1951 | WIA | PFC James C. Duggan |

| Roster Date | Total | Added | Dropped | WIA | KIA | Sick |

| June 30, 1951 | 229 | 31 | 42 | 47 | 2 | 44 |

Awarded Korean Campaign Battle Star for UN Summer Fall Offensive, July 9-November 27, 1951.

On July 9, 1951, the 10th Replacement Draft arrived. Six days later, on July 15, the entire 1st Marine Division was relieved and placed in reserve. We were relieved and went into reserve by descending from the hills, marching single file at a ten-yard interval. As we proceeded to the rear, we passed through an area occupied by an army artillery unit. There was no doubt that we were dirty, bedraggled, smelly and generally raggedy-assed Marines, having been on line for a period of five months. Our path took us about ten yards along the side of the clean, fresh faces of army troops lined up waiting in line for hot chow. Naturally, the army guys started to harass us with hoots and derogatory comments. I was at the front of our column and in no mood to accept abuse by rear echelon army troops. Swiftly, I swung the rifle from my shoulder, smacked the fore stock with my left palm and a resounding crack. I then opened the bolt ejecting the loaded round and let the bolt slide home with a new round. There is something about a bolt sliding home that even rear echelon army troops recognize. Suddenly all was quiet and we passed without further comment. I did not intend to shoot anyone, but I would have fired a warning shot over their heads if the abuse had continued.

| Roster Date | Total | Added | Dropped | WIA | KIA | Sick |

| July 31, 1951 | 232 | 57 | 54 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

We were continuously engaged as winter turned into spring, summer and fall, with some brief periods in reserve. Sometime during June 1951, I left the platoon and was assigned to duty as company intelligence scout.

When we were on line, my duties as Company Scout were to serve with Dog Company as directed by the Company Commander. Usually I was directed to serve with a squad, platoon or with the Company Executive Officer. Assaults or patrols were started each day with different platoons or, in some cases, a squad. However, I was always present as the company scout. Each day we patrolled and probed for the enemy, making contact and taking prisoners. Generally it was my job to take charge and assure appropriate handling of prisoners and to conduct a prompt preliminary interrogation to determine rank and unit and to identify and locate any other potential prisoners. My practice was to warn prisoners not to lead me into an ambush and then to follow them to search for additional enemy troops hiding nearby.

During the time we were in reserve, I reported directly to the Battalion Intelligence Officer (S-2) and performed various duties. On one occasion, I was part of a demolition team to locate and detonate artillery and aerial bomb duds. On another occasion, there was to be a nighttime demonstration of defensive fields of fire. My job was to scout the hill selected to be defended and to establish the defensive positions. That night Marines were moved into the positions and all weapons were firing live tracer ammunition. It was a spectacular sight.

Following is an article that was published in the Idaho State Journal on Tuesday, July 24, 1951:

Just one of the many worries confronting U.S. fighting men in Korea was reported Tuesday when a Pocatello and a Colorado Marine had a close call in the front lines. Pfc. Cyrill Barrett Jr., 22 of 618 West Clark, and Cpl. Perry J. Dickey, 21 Denver, passed an unfamiliar road marking on their way to the rear lines to enjoy a breather after some time up front. All they recalled were the rice paddies their company had passed on the way up to the front, but no mine field markings.

According to the Marine Corps report, the two searched their brains for explanations of the new danger markings. They glanced at each other and blanched. They were probably surrounded, at least out flanked, the report noted. Then Pfc. Barrett and Cpl. Dickey picked their way carefully to the GI rest area.

I have no memory of this event. However, C.L. (Barry) Barrett did recall and reported that after being on line for some time, the 7th Marines were placed in reserve. We had moved through an area that was later marked off as a mine field. Because we had passed through the area on the way north, our platoon leader, Lt. Brendan O'Donnell, ordered Barry to take the second squad and another platoon out of the area. Barry reported, our luck held and we returned to the rear without mishap.

At this time I was the Company Scout and the routine was for me to be assigned to participate with any squad or platoon that was patrolling or had an assignment. Apparently I was ordered to join with PFC. Barrett in leading some unit through the mined area. The reporter must have been present when we returned.

When we were advancing or attacking, mined areas were not usually marked. The most common marker for us was a small piece of paper from a cigarette package or C-ration wrapper that was held in place by a rock or twig. These mines were located by a Marine carefully probing the earth with a knife or bayonet. This probing often took place when we were under fire. There were no engineers with mine detectors in front of us, as the activity of mapping and marking mine fields was done after we had passed through or secured the area. It was interesting to observe all of the mined areas that were marked off when we went into rear areas. I never was able to determine if these mines were placed by the enemy before we passed through or later by the rear echelon troops as a defensive measure. We never had access to or used mines other than the use of hand grenades placed around defensive positions and rigged to be detonated by a trip wire.

As noted above, PFC. C. L. (Barry) Barrett was a native of Pocatello, Idaho. I first met Barry in Korea, when he was assigned to another squad in my platoon. At one time we had an opportunity to relax and talk and he asked if I had any relatives in Pocatello, Idaho. I replied that I did have an Aunt Anna Dickey that was a school teacher. Barry remembered my Aunt Anna as his first grade teacher.

George Golubosky is no longer alive and is worthy of some comment. We always called him Golubosky, never George or Sky. The name Golubosky sort of rolled out of your mouth and was fun to say. I believe Golubosky grew up hunting in the woods and hills of western Pennsylvania. He was a fine Marine with a heavy dark beard, and dark, deep set eyes. He had a fierce look and never smiled. His picture could be used with good effect on a pamphlet to be dropped upon the enemy encouraging them to surrender before Golubosky arrived. It was comforting to dig in with Golubosky, as he was able, alert, edgy, and had great night vision. One dark night Golubosky nudged me and asked if I saw the enemy in front of our position. I replied no, but Golubosky said that he could see them. I responded, "If you can see them, shoot them," and he did. The next morning there was at least one body, from which Golubosky removed and retained a Mauser pistol complete with a wooden holster that could also be attached as a stock. It is my understanding that later when I was no longer with the platoon, Golubosky was dug in with a new replacement. The new man was on watch and Golubosky was asleep. The replacement moved forward of the position to answer nature's call. He made two mistakes--going forward and not waking Golubosky. Unfortunately, Golubosky was aroused, and shot and killed the shadowy figure in front of his position.

Gus Felt is also worthy of comment. PFC Gus Felt was a very senior PFC, for reasons unknown to me, and he was an active Marine during World War II. Gus is also no longer alive and I believe he was about thirty at the time. Gus was a fine Marine, as we could rely on Gus to be in the right place at the right time to take appropriate action. As noted earlier, it was Gus who came forward, under fire, with grenades to render assistance after Sergeant Damon was killed. Gus held the grenade until the last possible moment and then delivered it on target with the desired effect. At a later date I was on a patrol with Gus when we left the body of a Corpsman in a minefield because we could only carry other wounded Marines. We carried the wounded Marines some distance to a more secure area and the wounded were evacuated by helicopter. Gus wanted me to return with him and recover the Corpsman's body. We were well beyond our perimeter, the sun was falling fast, and the Corpsman's body was in a minefield n the midst of the enemy. Gus was willing to go under these conditions, but I was not. My Marine spirit may have been lacking, but I saw no merit in risking further injuries or death to recover the body at that time. A few days later I was wounded by another mine and Gus was there to dress my injuries.

At the same time that I was wounded, Ki Hong Kim was in front of me and was also wounded as a result of the same explosion. Ki was our interpreter. He was about 16 years old, barely out of high school, and barely able to speak English. I needed another interpreter to clarify his English. Ki and I were attached to any Dog Company unit that went on patrol each day. We were assigned as needed when the company was engaged. I do not know how many others were wounded or killed, but Ki received the major impact and I was shielded or protected by his body. That was the last time that I saw Ki in Korea, and I believed that he had been killed. Later I learned that Ki's body was removed from the hill and thrown upon the enemy dead pile of bodies. At that time we had Korean civilian porters that were used to transport supplies over the rough terrain. These porters were disturbed, as they knew Ki and did not want his body to be with the enemy dead. The porters were standing around discussing the matter when they observed that Ki's eyes moved. The result is that Ki was evacuated and received treatment with the Korean Marines. Following the war, the Korean Marines also sponsored Ki to enter the United States as a student. Ki married, earned his PhD, and continued to live in the United States. I learned that Ki had not been killed when we were reunited at a Dog Seven Reunion in 1996.

On August 6, 1951, the 11th Replacement Draft arrived. On August 26, 1951, Dog Company was ordered to relieve friendly units on the Kansas Line east and south of the Punchbowl, with orders to take Hills 1026 and 924 that were part of the "Yoke"--a long east/west ridge just north of the Kansas Line. The next day, the entire 1st Marine Division was ordered back into the line.

| Roster Date | Total | Added | Dropped | WIA | KIA | Sick |

| August 31, 1951 | 234 | 28 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

The 12th Replacement Draft arrived on September 1, 1951. Two days later, the following Marines and a Corpsman went on patrol:

On this patrol (September 3, 1951), I thought I had been killed. I felt as if I were suspended about twenty feet in the air and looking down upon my body which was face down with arms and weapon extended forward and covered with earth and debris. The feeling was good and relaxed and I decided being dead was okay. Suddenly I began to stir and become uncomfortable and agitated. Soon I realized there had been an explosion and I had been hit with something or perhaps only the concussion had caused me to be unconscious or semi-conscious. The fact was a Corpsman about ten yards in front of me had detonated a bouncing Betty. The Corpsman was dead, three Marines were seriously wounded, and I was okay. Years later, I learned there were two mine explosions. The first one injured the Marines and the second one exploded as the Corpsman was proceeding to aid the injured Marines when he triggered another mine that severed his leg and killed him. The patrol consisted of a platoon leader, a squad, a corpsman, a radio man, a Korean Marine interpreter, Ki Hong Kim, and me. We had one dead, three wounded, and three or four prisoners. We had more injured and dead than we could carry so we proceeded with the wounded and left the Corpsman. Previously I have stated that I cared only about Marines and I must now make it clear that Corpsmen are considered to be Marines and the Corpsman was left with great reluctance as Marines take care of each other and leave no one behind.

| Date | Killed in Action | Wounded in Action |

9/3/51 | Corpsman Paul McMakin | PFC Paul F. Hassick PFC Lloyd H. Peebles PFC Alvin E. Graski |

9/3/51 - The pictures below were taken of the squad and prisoners after a patrol in Central Korea Area. P

PFC Paul F. Hassick, PFC Lloyd H. Peebles, PFC Alvin E. Graski were WIA and we had carried them to a more secure location and we were waiting for them to be evacuated by helicopter. Navy Corpsman HN Joseph Paul McMakin was KIA and left behind. The Corpsman's body was recovered later by Marines equipped to locate and disarm mines. Previously I have stated that PFC Gus Felt was present and wanted me to return with him to recover the Corpsman's body. Gus was not part of the patrol listed above, but he was present when we were waiting for the helicopter and must have arrived as a guide and to protect the photographer.