"I only wear the Medal of Honor for the men who were with me really. They earned it as much as I did. I accept medals on behalf of Love Company, 38th Infantry Regiment. We all fought together. This wasn't a one-man thing. A lot of people were involved. Men died just keeping me alive."

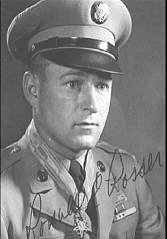

- Ron Rosser

[The following is the result of an in-person interview between Ronald Rosser and Lynnita Brown that took place in Mr. Rosser's home in Roseville, Ohio, on July 29, 2004. Initial contact with Mr. Rosser was made on behalf of the KWE by Delmar Wilken (Heavy Mortars, 2ID) of Champaign, Illinois. The trip to Ohio to conduct the interview was privately funded by KWE members Martin Markley of California and John Kronenberger of Illinois. Mr. Rosser's neighbor, Paul Mills of Roseville, Ohio, assisted Mr. Rosser in receiving drafts of the interview and memoir via the internet. Local author Joanne Boring offered her assistance, too.]

Cpl. Rosser, distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry above and beyond the call of duty. While assaulting heavily fortified enemy hill positions, Company L, 38th Infantry Regiment, was stopped by fierce automatic-weapons, small-arms, artillery, and mortar fire. Cpl. Rosser, a forward observer was with the lead platoon of Company L, when it came under fire from 2 directions. Cpl. Rosser turned his radio over to his assistant and, disregarding the enemy fire, charged the enemy positions armed with only carbine and a grenade. At the first bunker, he silenced its occupants with a burst from his weapon. Gaining the top of the hill, he killed 2 enemy soldiers, and then went down the trench, killing 5 more as he advanced. He then hurled his grenade into a bunker and shot 2 other soldiers as they emerged. Having exhausted his ammunition, he returned through the enemy fire to obtain more ammunition and grenades and charged the hill once more. Calling on others to follow him, he assaulted 2 more enemy bunkers. Although those who attempted to join him became casualties, Cpl. Rosser once again exhausted his ammunition obtained a new supply, and returning to the hilltop a third time hurled grenades into the enemy positions. During this heroic action Cpl. Rosser single-handedly killed at least 13 of the enemy. After exhausting his ammunition he accompanied the withdrawing platoon, and though himself wounded, made several trips across open terrain still under enemy fire to help remove other men injured more seriously than himself. This outstanding soldier's courageous and selfless devotion to duty is worthy of emulation by all men. He has contributed magnificently to the high traditions of the military service.

Cpl. Rosser, distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry above and beyond the call of duty. While assaulting heavily fortified enemy hill positions, Company L, 38th Infantry Regiment, was stopped by fierce automatic-weapons, small-arms, artillery, and mortar fire. Cpl. Rosser, a forward observer was with the lead platoon of Company L, when it came under fire from 2 directions. Cpl. Rosser turned his radio over to his assistant and, disregarding the enemy fire, charged the enemy positions armed with only carbine and a grenade. At the first bunker, he silenced its occupants with a burst from his weapon. Gaining the top of the hill, he killed 2 enemy soldiers, and then went down the trench, killing 5 more as he advanced. He then hurled his grenade into a bunker and shot 2 other soldiers as they emerged. Having exhausted his ammunition, he returned through the enemy fire to obtain more ammunition and grenades and charged the hill once more. Calling on others to follow him, he assaulted 2 more enemy bunkers. Although those who attempted to join him became casualties, Cpl. Rosser once again exhausted his ammunition obtained a new supply, and returning to the hilltop a third time hurled grenades into the enemy positions. During this heroic action Cpl. Rosser single-handedly killed at least 13 of the enemy. After exhausting his ammunition he accompanied the withdrawing platoon, and though himself wounded, made several trips across open terrain still under enemy fire to help remove other men injured more seriously than himself. This outstanding soldier's courageous and selfless devotion to duty is worthy of emulation by all men. He has contributed magnificently to the high traditions of the military service.

Photo Album

My name is Ronald Eugene Rosser of Roseville, Ohio. I was born in Columbus, Ohio, on October 24, 1929, a son of John Milton and Edith Marie Riffle Rosser. Although I was born in Columbus, but I grew up in the Roseville/Crooksville area of Muskingum and Perry counties. I lived many years in Perry County and entered the military from there.

During the Depression my father worked as a carpenter building the big mansions in Columbus. But primarily he worked in underground coalmines. The coalmines are all gone around here now, but back then he worked for several mines owned by Earl J. Jones. My father worked his way up through the company on various bossing jobs until he became superintendent in charge. He worked in the mines until the late 1950s. During that time, coalmining started getting modern equipment like cutting machines. Before those came along, miners had to use a pick. They had to undercut the coal and shoot it down, and they didn't get much coal. When they started using a cutting machine to cut way back into the coal, the mines produced more coal. As I was growing up, everybody figured that I was going to be a mine boss someday. All my family were mine bosses. That's just the way things were. But I decided early on that I didn't want to be a boss. I wanted to be a soldier.

My mother didn't work outside of the home. She had 17 children—nine boys and eight girls. My siblings were Evelyn, Eleanor, Richard (KIA, Korea), Jimmy (who died as a child), Reta Patricia (known to us as Patsy), Joanna (who has passed away), John, William or Bill, Shirley, Donald or Donnie, Sandra, Judy, Diane, Roger, and the twins Larry and Gary (KIA, Vietnam). My mother became pregnant in 1928 and she stayed pregnant until 1946. All of my mother's children were born at home. We moved back to this area when I was maybe six months old and we lived in a six bedroom house, which was as big as they get around here. My father always made reasonably good money, more so than other people around here, but he had a large family so it all balanced out. I'm sure we were poor during the Depression and didn't know it. My father worked 12 hours a day. He didn't have time to grow food for the family. He always put in a garden, but weeds always got it before we did.

None of us went to school in Columbus. We went to school in the Crooksville area. I went to the Crooksville and Roseville elementary schools. They're all gone now. In fact, my brother Richard went to a school which was right across the street from where I live now. The building is gone and it is now a park.

When I got to be about 13 years old I had a paper route. The paper doesn't exist anymore. It was the Zanesville News. The gentleman who owned the coalmines where my dad worked owned the Zanesville News. He wanted to publish some statements in another local newspaper and they wouldn't let him, so he started his own newspaper. Earl Jones had a thousand people working for him in this one mine. He made the statement that the payroll of this mine made a big impression on the economy of Zanesville and some said that was a bunch of crap. To prove his point, Mr. Jones paid everybody in silver dollars for a while. A lot of the mining families shopped in Zanesville. The stores had to put big buckets on the counter to hold all the silver dollars that started coming in. Mr. Jones made his point. When he started the Zanesville News, he built a building, brought in printing presses, hired the newspaper people and the paperboys, the whole thing. He had the first issues of his paper on the street in 30 days. Because my father worked for Mr. Jones in the mines, I got a job as paper boy for the Zanesville News.

I was in junior high and high school during World War II. It was over 60 years ago, but I remember they used to have scrap drives to bring in this and that. My Uncle Carl Riffle was in the military and so was my Uncle Albert. Only Carl went overseas. He served in the Third Army and always said he was in Patton's Army. Something happened to Albert in the military. He was a T-4, they called it back in those days. He was hurt and after that he was discharged. I followed what was happening in the war by listening to the radio and reading newspapers. Everybody followed it. What was happening was common knowledge. The news was always a month late getting here, but everybody followed it.

I lived on a farm with my Grandfather Alonzo Riffle and Grandma Riffle a lot in the summer times. When I was 13/14 years old when school was out, I used to go out and live in the woods by myself. I liked to be able to go out and just make my own way. I put a little pack on my back with a half box of .22 shells, a little salt to put on the wild game I killed to eat, and a skillet about the size of my hand. I rolled up a little blanket and a piece of canvas and carried them with me. I also had a little .22 rifle with me. I grew up knowing how to shoot. I guess it was just natural. I hunted squirrels and I hunted rabbits during season when I was just a kid. I was a very good shot. I could shoot squirrels through the head with no problem with my .22. Not a shotgun. A little .22.

I traveled all over the area. I don't think Mom missed me until I was gone about a week. Sometimes I'd be gone 30 miles from here to wherever it took me. I'd shoot my own game and cook it when I got hungry. Live off the land. Nobody went with me and I liked that. I was alone a lot. I was always gone from home. Even in my dreams I was gone from home. I wanted to go see the world. I think my greatest fear was growing up, working, getting married, having children, and dying in this area without a chance to see the world.

I left school when I was in the tenth grade. I got a job and went to work. I worked in a pottery factory in the china packing department. Ohio is famous for its pottery. Crooksville China was probably one of the best china companies in the United States. I packed the china by sets to get it ready for shipping. I worked in a couple of those places.

I joined the Army in 1946 as soon as I turned 17 years old. Nobody worried about me dropping out of school and joining the Army. I had reached that age where I wanted to do what I wanted to do, so I joined. At first I wanted to join the Army Air Corps (it was all the Army back in those days). I didn't want to go into the Navy and didn't particularly want to go into the Marine Corps, so the Army was it. I always have a joke I tell people about going into the military. My mother had 15 children and she was about to have another child, so my brother Richard and I were downtown just keeping out of the way. When we came back home, one of my sisters was out on the porch waving her arms saying when we got close, “Ron, Momma had twins.” I turned to my brother Richard, who later got killed in the Korean War, and said, “Well, there goes my place at the table. I'm joining the Army.” But I was already going in. The twins were Larry and Gary. Gary was later killed in Vietnam.

To join I went to Ft. Hayes, Columbus. They sent me from out of Zanesville to Ft. Hayes and then from there to Camp Atteberry, Indiana. From there I went to Ft. McClellan, Alabama, and then I went to Ft. Benning, Georgia, to parachute school. From there I went to the 82nd Airborne. I think I left Ohio by train. There were people out of the Zanesville area that went into the Army at that same time, but they were not friends of mine. I didn't make friends very easily. I still don't.

I had no problems at all in basic training. Some people did. Some didn't like being away from home. Some got sick. There were a lot of reasons why people fell to the wayside. Our days in basic training were regimented--we got up early and we went to bed late. Back at home I always slept in a bed with my brother, but in basic I had my own bed. They fed us well. It wasn't like Momma cooked, but it was okay. I was an expert rifleman from Day One.

After basic I volunteered for parachute school. It sounded good to me and I've always been a risk-taker. Training was tougher than hell. It was physically tough and mentally tough. They kept the pressure on us. We never walked anywhere--never. We double-timed everywhere, even to the bathroom. We were lucky if they let us sit down. Every time we blinked our eyes, we had to do 10, 20, 30 push-ups. We were constantly doing exercises.

There was no classroom training. We had a series of different types of training taught by other parachuters. They had been at Ft. Benning for a while and most of them had been in wars. Some of them were in the original test parachute platoon from 1939. (Later on when I became an instructor at parachute school, some of those same people were there.) We had to learn to pack our own parachute, which we jumped. We had to learn about gliders and how to tie knots--the different kinds of knots to tie jeeps and howitzers and stuff inside of gliders. We also had to learn how to maneuver parachutes and so forth. Then we went up and jumped.

They had a 34-foot tower that we jumped out of and slid down a cable. It was really just to give us confidence in getting out the door. Then we went to a 250-foot tower where they pulled us up and dropped us by parachute. That was to get us used to having nothing under our feet. It was a funny feeling when we were hanging up there (and then on the way down) with nothing under our feet for the first time in our life. From there we started jumping out of C-46s and C-47s. They were called "Gooneybirds." The first time I jumped, I was ready to roll. In fact, I led the stick. There were eight of us and I was the lead man.

After leaving Ft. Benning, I was sent to the 82nd Airborne Division at Ft. Bragg. They put me in a heavy weapons platoon of what they called a support company, and I became a mortar man in 4.2 mortars. The 4.2 mortar was the biggest mortar we had at that time. The base plate alone weighed 150 pounds. It took a minimum of two people to carry it, and they couldn't carry it very far. It had a tube and a fork in front. In airborne we put it on a two-wheeled cart to transport it and we dropped it by parachute while it was still on the cart.

All we did all day long was gun drill. They trained us to be forward observers, radio operators, and everything that had to do with 4.2 mortars. I was in airborne the first time for the better part of two and a half years. Off and on I was in the airborne for over 20 years. I liked it, although I found it restrictive. We had a tight schedule and were told when to eat, when to go to bed, when to do this, when to do that. At the end of my enlistment I got out. I wanted to find something else.

I got out of the Army in 1949 and did a lot of running around and having a good time. My father thought that I had had a good time long enough and it was time for me to go to work. He said to me, “Ron, when are you going to get a job?” I told him that I was looking--which I wasn't. He said, “Well, you can stop looking. You've got a job.” When I asked him where, he said, "In the mines with me." He said I was to start the next day. I went to work the next morning and remained in the mines for a year and a half, doing the most basic labor a person could do. I worked on the machines that were used to cut the coal. They made a big cut of coal and then they took a joy loader to get it all out. They dumped the coal on pans that carried it out to the belt. We had to put on extra pans. They were very, very heavy, weighing in the neighborhood of probably 300 pounds. Because they were so heavy, we had to drag them over, bolt them up, and put on the tail start. Those tail starts weighed 150 pounds.

I shoveled a lot of coal in the Misco Mine. It had low top, which meant that we were always bent over a little bit. Sometimes we were bent over very low, depending on the seam of coal. There is always water in a coalmine, but there was not really much in the Misco. Once in a while they ran into water, but if they did, they had sump pumps that pumped it out. I didn't hate the job and I made good money. But I didn't want coalmining to be my career. I was looking at other things. I had a friend who was in high steel (building skyscrapers) and he thought I would be real good in that job. I was thinking about, but my kid brother Richard went into the Army and got killed in Korea, so I decided to re-enlist.

Richard enlisted when he was 18 years old. I was out of the service by that time and working in the mine. Richard was next to me in age. When he entered the service, none of the family members were concerned about it because it was peacetime. There were things going on around the world, but nobody worried about that. He was in the regular army and was in the 3rd Division down at Ft. Benning, Georgia. He was home on leave when the Korean War broke out. He got a telegram telling him to report straight to Korea. He got there in early July of 1950. He was in the 24th Division originally.

He was wounded at a place called Taejon. Actually, he was pretty lucky that time because he got wounded early in the battle. They evacuated him out before the division got overrun. Even the commanding general was captured. I remember the family getting the telegram saying that he had been hurt. My mother and father were concerned, but I don't think I was because I had been around the army. I knew that if you got wounded and you got evacuated out, they took care of you. Richard called my mother from Japan when he was in the hospital and told her that he was okay. If he was in good enough shape to call home, we figured there was nothing to be concerned about. But then they sent him back into combat. He actually wasn't well enough to go back. His forearm was in a cast and he had fingers gone off of both hands, but they needed soldiers to fight.

He was in the 1st Cavalry Division when he went back on line and was killed in a tank/infantry assault trying to break through to the 2nd Division, which was trapped at Chipyong-ni. He got killed on the 10th of February 1951, but we didn't get notified until a few days later. They called my mother from the telegraph office and said, "You've got a telegram." She and my father went down there and got the telegram saying that he had been killed. The whole family was pretty shook up over it. We were a close knit family. I sat around trying to think about what to do. I was the oldest son. When somebody bothered my family, I punched their lights out, so to speak. If someone bothered one of my sisters, they'd better leave town. That's the way I grew up.

I finally decided in early May to re-enlist. Of course, my father didn't want me to go and talked to me about it, but I finally just said I was going and re-enlisted. I requested combat duty in Korea. I understood that my parents didn't want me to go. I also knew that I couldn't kill the person who had killed Richard. But I finally made up my mind that my brother didn't get a chance to finish his tour, so I was going to finish his tour for him as a combat soldier. So that's what I did. I wanted to get even for him and finish his tour.

I re-enlisted in the middle of May 1951. I had to process again and go through various things. They sent me to get an issue of clothes and I had to meet one requirement of going through an infiltration course. They sent me to Camp Breckenridge, Kentucky, to meet the requirement. I had to crawl under barbed wire for five minutes with a machine gun shooting over my head. That's the only thing I had to do to be qualified for combat.

They shipped me out to the west coast and put me on a boat. I was still airborne. An airborne outfit over in Korea got hit real hard in a battle just before I got to Japan, so they pulled them back to Japan to get replacements. They couldn't just put regular infantry in an airborne, so they started grabbing every airborne guy that even got near that area. When my ship docked in Japan, they took me off the boat and sent me down to the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team to support company. There, they put me into the 82nd's 4.2 mortars. We were in training, but got passes to go here and there. I went around to some of the cities that got hit by bombs in World War II. I didn't like the Japanese people. I remembered Wake Island, Bataan, and the things I grew up with--Guadalcanal and the Islands. I just didn't like the Japanese.

I asked the people in the 187th if they were going to Korea right away and they said it would be a while. I knew a lot of the people in support company because they came out of the 82nd support company. I was good friends with a soldier out of Alaska. (I called him Eskimo.) He retired as a command sergeant major and, in fact, he called me a couple of years ago just to get in touch with me in our later years.

Anyhow, when they told me they weren't going over to Korea any time soon, I told them I wanted out of the 187th. I told them, "I'm scheduled for combat duty in Korea." They said I couldn't get out, but I said, "Watch me." I had specifically enlisted for "combat duty Korea." When they stopped me at the 187th Airborne, they couldn't hold me because I had an option. I went up to them and told them, “You've got to turn me loose. I've got a combat assignment. You people aren't combat. You're violating my enlistment option.” They said okay and put me in with a bunch of other people that were trying to get back to Korea. Within two weeks I went over to Korea in a replacement packet of 101 replacements.

We were originally scheduled for the 7th Division, but the 2nd Division was around the Punchbowl and was hit real hard, so they changed us from the 7th Division to the 2nd Division. I was put in the 38th Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Infantry Division. First they wanted some volunteers for the I&R platoon. I didn't think I'd like that, so I didn't take that. Then they said, “Are there any people here with experience in 4.2 mortars?” I had spent quite a bit of time with the Four Deuces, so they sent me up to heavy mortar company. They took all the rest of the guys and broke them down into three battalions. Only a couple of those guys made it through the whole thing. They weren't all killed, but they were either all killed or wounded and evacuated. Only a handful stayed in the regiment.

My first impression of Korea was that it smelled bad. Everything smelled--the country and the people. Those people didn't take a bath. They had no food. Their homes were gone. There were refugees everywhere. Hundreds of thousands of refugees everywhere. Children without families starving to death. The closer I got to the front, the bodies weren't buried and I could smell them. Everything smelled bad. In fact, on the way up to the 38th Infantry, we were going real slow around the road and I looked down and saw a truck upset. I could see the bodies sticking out underneath of it. I don't know if they were American bodies. Nobody seemed to care. We were heading into the front and we could hear the firing and knew that it was going to get worse. By the time I left Korea a year later, I had seen flies above the heads of thousands of Korean War dead. There were so many of them they looked like a black cloud--flies and honey bees.

I'm not sure if I was apprehensive or if I looked forward to being in combat. I thought about Richard. The artillery was back quite a ways and although we could hear the firing up ahead of us, we weren't even to the artillery. There were long lines of ambulances and litter jeeps coming back with wounded in them. I think my first impression of this was, "Everybody thinks they're lucky and here is a whole bunch of folks who weren't." I knew it wasn't going to be like I thought. I thought it was going to be "bang, bang," you know. I wasn't worried about it one way or the other as long as I got my shot. They sent me up to Heavy Mortar Company. There are heavier mortars now, but it was the heavy mortar during the Korean War. It was like the 105 artillery piece. Very accurate.

The 38th Infantry was on the edge of the Punchbowl when I got there. The first place I went in on there was the final battle at 1179, the mountain overlooking the Punchbowl. It was strategic because it was high. It was commanding ground where whoever owned it could see the enemy below. When they sent me to the heavy mortar company, the company commander said, “Well, Ron, you're an experienced mortar man. I'll put you down in the third platoon as a first gunner.” We had a very strong disagreement about that. I told him that I wasn't going to the third platoon, I was going up on line. He said, “You're going to the third platoon, Rosser.” Then I said, “No I'm not Captain. I'm going on line.” I remember that he told me he was running the company and that I was going to the third platoon. I walked right up to his face, stuck my nose right in his eye, and said, “Captain, I'm not going to third platoon or any other platoon. I'm going on the line.” He was kind of taken aback by that because he wasn't used to that kind of back talk.

The Heavy Mortar Company with its heavy weapons was the main support for the 38th Infantry Regiment. Its various platoons--first, second, third, and so forth, each had their own sector of fire. They were all lined up behind the 38th Infantry. That way one forward observer could call fire from all of them. The Captain told me, “The only people we have on line are forward observers and radio men.” I told him, “I'm the best forward observer you've ever seen, Captain.” And he said, “We don't need any forward observers.” When one of the people spoke up and said, “Hey, Fridel just lost another radio man,” I said, “I'm also the best radio man you've ever seen.” The captain said, “Okay. You're on the line.”

I wanted to be on line because that's where the killing was. I was going to do my part. I wasn't going to sit there and pound them with mortar fire. I wanted to look at them. So I went up on line. I went onto 1179 into what they called the Bloody Ridge with Richard Fridel. He went down within a few days wounded and I became the forward observer. They sent a radio man up to me who I don't even remember. From July of 1951 until the first of May 1952, I had eight radio operators and lost seven of them killed or wounded I tried to get this one guy in the company to be one of my radio men, but he said he stuttered. (The one thing a forward observer couldn't have in a radio man was a guy who stuttered.) He had arrived at the company before me and was right there when I reported in and told his company commander that I was going on the line. He told some people, “This guy thinks he's an Audie Murphy." Later on he joined the 2nd Division Association, and when he was at the association meeting filling out his papers stating that he was from Heavy Mortars company, they told him there was a guy from heavy mortars who got the Medal of Honor. He said, “You're kidding me,” and asked if they knew who he was. When they said they weren't sure what his name was he said, “I'll bet I know who it was. I'll bet it was that crazy guy that wanted to go up on the line. He was crazy.”

A forward observer was up with the forward elements of the infantry. My job was to call in mortar fire on the enemy whenever they exposed themselves or wherever I thought they were--both offensive and defensive fires. A forward observer looked out over the terrain, and if, for instance, I saw 500 enemy out in the enemy, I said, "Fire mission. Enemy troops in the open." The FO had to decide what type of fire he wanted. For instance, if I caught them in the open, I hit them with heavy explosions--right on. And normally if there were a lot of them, I used all three platoons. If there was just a little bit, I only used one platoon, depending on what the target was. As soon as I hit them with heavy explosives, they would go to ground (get under cover). So then I changed to white phosphorus and it would explode and go down on them like rain. It would set them on fire and they would jump up to run again. Then I would hit them with the meat grinder. White phosphorus was a chemical that burned as long as it had air. It could not only set someone on fire, it could burn right through him.

An FO was right on the front line. Actually when I was there, there was no front line. We were assaulting every day and defending every night. They hit us every night and we assaulted them every day. They hit us mostly under cover of darkness, although they hit us in the daytime too. When it was dark, our Air Force couldn't get to them. At night we lost our Air Force as a defensive weapon. Then we only had artillery and mortar fire to protect us, plus the infantry weapons. The enemy stormed in by the hundreds, sometimes thousands. They would hit one place and just overrun us. Sometimes we had warning they were coming. They communicated with each other by blowing bugles and they used flares, pyrotechnics, and so forth. They used different noises to mean different things.

I never went into reserve. My unit pulled into reserve coming off Heartbreak Ridge and the whole regiment pulled out. As soon as they pulled the regiment off, they shipped heavy mortar company over behind the Turks and I went on line with the Turks as a forward observer. They were pretty good fighters. I didn't trust them because I mostly didn't understand what they said. Of course, it wasn't just the Turks--I didn't trust anybody. I was always a loner. I never knew anybody. During the war I very seldom knew anybody's name. They'd say, “Ron, you're to report into I Company at the such and such grid coordinates. They're jumping off in the morning. Go across country and catch up with them and jump off with them."

I had radios, a compass, binoculars, and maps to help me plot concentrations and call fire in on the enemy. If my platoon was here and the enemy was up there, I could be off to the side. When I called fire in, I called it from a certain azimuth. My platoon or company never knew exactly where I was at, but they knew I was on that line from that azimuth to the enemy. When I directed my fire, I went left or right of that particular azimuth and changed not from the platoon, but from my azimuth. I could give a group of coordinates or march into a sector. There were lots of different ways I could get fire out there. A lot of times when I was using artillery or tank fire or something like that, I liked for them to mark the center of a sector and I went from there.

From July to about the first of August or to the middle of September, we were on Bloody Ridge. From Bloody Ridge we went over to Heartbreak Ridge. We had a one-day truck ride to move everything over there. During the battle for Bloody Ridge, there was fighting and being attacked night after night. At the same time, peace talks were going on. That's the nature of war, I guess. In my time, nobody believed that the peace talks were worth a damn. One of the humorous things I remember about Korea was when a lieutenant came up to the OP to check everything out before the Turks moved out and we moved in. Just before he got there we went out to the barbed wire in front of the outpost and brought back the body of a mangled, twisted Chinaman who had been killed a long time ago. His body and those of a lot of other Chinese had frozen right onto the wire and we had just left them there. We set him up around the table where we were playing cards and when this lieutenant came up and asked if we thought the peace talks were going to end, we turned to the dead Chinaman and said, "What do you think, Joe?" The lieutenant said, "Christ! How long has this guy been out here?" It was funny.

We had objectives while the peace talks were going on. We wanted to get the controlling ground in our sector, which was the central sector. We wanted it so we could control both sections of the line and straighten the line out. The line was kind of like a saw tooth. We straightened the line out the best we could and took out the big dips in it. That's what we were doing over in the Bloody and Heartbreak Ridge area--just moving up to the lines at the narrowest part across Korea where it was easiest to hold.

After Heartbreak Ridge fell, I then moved up with the Turkish Brigade. This was in November of 1951. The reason I moved up with them was because, when it got up to strength again, my regiment was going to relieve the Turkish Brigade up in the Kumwha Valley. My job was to set up concentrations across the entire regimental front so that my regiment could replace the Turkish Brigade with very few casualties about mid-December. My job was to protect the soldiers and to know ahead of time what was happening before my regiment came up. I knew who was coming up and where they were going. They were going to replace the whole Turkish Brigade, so I put out intensive fire wherever the enemy could possibly hit us. I had concentrations clear across the regimental front. If they came 50 yards away from the concentration, I could move it and fire would be on them. In reality the regiment relieved the Turkish Brigade without incident. They came in at night, the Turks pulled out, and we moved in right above them.

At this time I was doing what I wanted to do. I was looking the enemy in the eye. They were the regular army of the North Koreans. Many of those people were hardened combat soldiers. Some of them had years and years of combat experience. They had fought with the Communist Chinese against the Japs that had fought against the nationalist Chinese. They were as well-equipped as we were. We had World War II weapons and so did they. All day long we assaulted their positions in a particular sector in the mountains. Sometimes I was maybe on my third company before we took the objective. I started out with A Company. When A Company was down to 15 men, they held and B Company pushed through. I went with B Company until they were down to a handful of men, and then C Company pushed through and we continued to assault the top. We just kept going until we literally chewed the enemy up. They counterattacked us and actually we were fighting very close--sometimes hand-to-hand.

Nobody is actually trained for hand-to-hand combat. Oh, they gave us bayonet training and they gave us training in jujitsu and that kind of thing, but nobody ever dreams of doing that kind of stuff. It's one thing to shoot a guy and it's another thing to stick a bayonet through him or beat him to death with a rifle. I've done both of those. I never felt like I was killing a human being. It felt more like I was killing a rat. I didn't have any conscience about it. I think we were just better at it than they were. We could throw a hand grenade further than they could. We could do a lot of things better than they could.

At first, thoughts of my brother Richard who had been KIA was my guiding light, so to speak. That's what got me to Korea. But after I got there, I did it because it was my responsibility to do it. My job as a forward observer was to protect those people that were there and to cover them during their assaulting or defending. My job was to put out defensive fire when they were being attacked. I had a responsibility to those people to make sure I kept them alive and to help them hold whatever they had. My driving force was responsibility. Thoughts of my brother were always there and I remembered, but I had all those other kids too. I never knew any of their names, but I felt responsibility for them. For the most part I was older than them. Sometimes they were ten years older than me, but they were still "kids" because I had more combat time than they had. After they were there three or four days, they were as old as me.

I lived in a hole in the ground. During the assault during the summer, I lived in a shell hole or a trench or anywhere I could get below level ground to get some protection from incoming enemy fire. Very seldom did I ever get in any bunker, although I did up on Heartbreak Ridge. I got into the bunkers there because the fighting was pretty intense--more so there than on Bloody Ridge. On Heartbreak Ridge the enemy threw everything they had in there trying to hold it. They knew that if we took that area, they would lose a whole section of the ground behind them and they would have to pull back. If we had the high ground we could see them whether they were. The enemy always knew where we were at, too. They could see us. Sometimes we were only a few yards apart. They could hear us breathing. Hell, I knew where they were too. I could smell them.

I don't remember any lulls in the fighting in the summertime. It seemed like we were never out of a fire fight--we were always knee deep in it. I called in fire day and night. It's hard to remember one particular battle because it was all a battle. Day and night, week after week. I got hungry and thirsty and I was dead tired, but so was everybody else, so I didn't worry about it.

In the summertime and early fall when we were able and moving, if we passed a stream we washed our feet and whatever else we could. Baths were almost non-existence. If we had a chance and we were reasonably safe, we could take off our clothes (which were pretty battered), get some water in a helmet, and just rinse ourselves or wash ourselves off as best as we could. But in the wintertime there were no baths. We were covered with lice and fleas and there was nothing we could do about it.

I almost never got mail and things at that time. I wrote and asked my mother to send me some sardines. She thought I loved them. I did, but not for the reason she thought. I opened them and let them sit out until they rotted. Then I put my extra bullets down in them. If the bullet didn't kill the enemy, the infection would. I had a mean streak. One guy used to call me the "gunfighter" all the time because I shot from the hip in close combat and notched my carbine after I killed someone. I just did it to be "colorful."

I had been in Korea for a long time. I knew what I was doing. Nothing excited me very much. But the kids (when I say kids, some were older than me and some were younger) got scared and I had to talk to them kind of soft and easy. For example, there was a medic that I knew real well. These kids knew they were probably going to get killed or wounded in these assaults and this medic used to tell them, “If they don't kill you instantly through the head or the heart, there's nothing they can do to you that I can't fix.” He said this to give the kids confidence. Being quiet and calm and everything gave the kids confidence in us. These kids knew that wherever I was at I wasn't going to run, and they felt they would be safe.

Up on the Heartbreak Ridge we got some replacements in one time. They sent them up to the company commander but he didn't need them right then and didn't have time to fill them in and tell them what to do. He said, “You go back over to that guy over there, Rosser. He'll take care of you and keep you alive until I need you.” They came over and reported to me. One of them was a Staff Sergeant and he asked what he should do. I said, “Get your people into that big bunker over there and stay there. Don't come out unless I tell you to come out. If the enemy gets close, get out here and get in the trench where you can fight. Keep your weapons handy, but don't worry. You're perfectly safe there as long as you stay there. They're not going to get back here any more. We'll keep them off of you.” That staff sergeant survived Korea. I ran into him several years later down at Ft. Benning, Georgia. He was a master sergeant then. We were good friends. He thought that I was just about the meanest guy that ever lived--and at that time, I was. I wasn't afraid of anybody--or if I was, I never showed it.

Sometimes I got a little apprehensive. One time I dove for cover to get away from a mortar round. I dove over this ridge and as I was coming down I saw that I was going to land on a shoe mine. Rain had washed the dirt away from it and that's why I could see it. I knew that I was going to get blown all to hell and back. I hit screaming, but not a word ever came out of my mouth. I screamed in my mind. I landed right on it, but it was a dud. Apparently the water had done something to the fuse and it didn't go off.

I got nicked a few times in Korea. I got the Purple Heart for one of the wounds. I got hit on the Bloody Ridge in the foot and I got hit in the leg on the Heartbreak Ridge. When a person got a cut on his foot he didn't run down and say, "Hey, I got a Purple Heart." If someone got nicked, maybe later on some guy would say, “Hey, I got hit up there. Here's where I got hit.” They would say okay and mark them down for a Purple Heart. That took care of it. But I would have been ashamed to go down there where they had all the dead and wounded, trying to take care of them, and then say, “Hey, I've got a cut on my foot.”

I was involved in one incident that were a closer call than I wanted it to be. I was up on the Bloody Ridge with George Company of the 38th Infantry. Each regiment had letter companies such as A, B, C, D. That particular day I was out with George Company. We were in kind of a company outpost way out in front of the main line when we got hit by what I would estimate to be a brigade of North Koreans--maybe a couple of thousand. Somewhere close to that. They were on us and only about half of us made it back to the main line. I barely got out. They were hot on me when I hit the line. We fought them off as best as we could and we killed a lot of them. They caught some of the guys that were 75 yards from us and we couldn't get to them. They stood them up one at a time and made them holler. When they couldn't or wouldn't, they shot them and sent another guy up. They killed them all. We could see it, but we couldn't do anything about it. They had them. The North Koreans weren't out in the open, but the kids were.

Through the years a person's memory dims. Sometimes I have dreamed about something and haven't been sure whether it actually happened or not. I used to tell my wife about this particular incident. One day a kid came down from Columbus and wanted me to autograph a book for him. We were talking and got on the subject of prize fighters. It just so happened that in George Company there was a guy that had been the lightweight champion of the world. "Lew" Jenkins was one of the guys that made it back the day the North Koreans shot those kids in George Company. When he wrote his memoirs, Jenkins talked about that incident.

I never saw a live North Korean after that happened. I made sure they were dead. I killed them all. If their wounded were there, I shot their wounded. I shot everybody. I didn't even care. If we were in the assault and we had to go by an enemy wounded and there were grenades and weapons laying all over the place, I sure wasn't going to leave him laying there behind us where he could shoot us or throw a grenade at us or whatever. So when I went by him, I just shot him. He was the enemy and if he had the capability to continue to fight us, I killed him. And I killed him without mercy, too. I think one of the reasons why I didn't like the North Koreans was that they made me just like them--where I killed without mercy. We all did. Up on Heartbreak Ridge we actually got orders (I'm not sure who issued them) to take no prisoners. The regiment was shot all to pieces. We didn't have people to handle prisoners, so we just killed everybody. They were there and we killed them.

There were guys in my company or my squad that were killed just because a dumb mistake was made. I think everybody got killed because of dumb mistakes actually. People did stupid things. They raised their head up when they shouldn't. They just did certain things and they got killed. An example of this would be a patrol behind enemy lines moving from cover to cover. Suppose they got up to a stretch of 25 yards that they had to go down but there was no cover and the guys in front of them moved out. They ran through. Maybe four or five guys would make it and then one guy would get shot down. Then four or five other guys would make it and then another guy would get shot down. Then comes your turn to run. You know what I mean? Those who get shot are just unlucky. They're the ones late hitting the ground when they hear rounds coming in. The guy that gets to the ground the fastest lives the longest really. We learned to pick up that habit. Move until we heard something and then we ducked. We learned to tell the difference between a bird chirping and a flutter and a mortar round coming in. We only had a split second to live if we were wrong. A guy's senses are heightened when he is in combat. He sees better. He hears better. He thinks better. I fought the enemy in close combat and it was like they were in slow motion sometimes. I mean, I fought them in hand-to-hand combat fighting where I actually beat people to death with a rifle. I've had people turn on me shooting point back at me with sub machine guns just inches away and they never hit me. The point I want to make is that we learned to react a little faster than we normally would. We were constantly moving. We didn't stay in one place. Maybe we only moved inches, but those inches made a difference sometimes.

I never actually stayed with my company. The company commander that was CO when I came into the company went home right after I came there. I had a couple of other company commanders, but I almost never knew them because I seldom went back to my company. I was always up at the line company. I was with a lot of different line companies all the time I was in Korea. I served in combat with every line company in my regiment plus every company in the Dutch battalion and the Turkish Brigade. I was never an integral part of any of these companies. I was just attached to them for a while. I loved being a forward observer because I could do a lot of damage and make a lot of noise. I could kill more people in my sleep than an average guy could kill in a lifetime.

In December of 1951 and January of 1952, we were up in the Kumwha Valley running deep patrols into the enemy lines toward Pyongyang at the point of the Iron Triangle. We were also getting hit all up and down the line. The fighting involved not just one person or one company, but a lot of people and a lot of units. Around the 17th or 18th of December, the Chinese broke through the line. We got hit hard and a lot of people got killed. This went on for several days.

The day before Christmas I went out with a reinforced platoon of I Company on a combat patrol. Seventy-three of us went out and six of us made it back. I remember that day because we were wiped out. Every man was killed or wounded but me. I brought Fridel, my radioman, out because his leg was torn up. (Fridel was the guy who had been the forward observer before I took over.) He went back to the rear for a long time and when he came back he was crippled up. They didn't send him into combat anymore.

On the day of this patrol, we had penetrated probably close to three miles behind enemy lines before we were hit and came under a heavy mortar/artillery barrage out there. It was point blank fire really. As soon as the Chinese hit us, man, they swarmed in on us. I mean they hit us hard. Our platoon leader was killed. His assistant was a young lieutenant. He just panicked and said, “Let's get out of here.” The guys started trying to get out, leaving their dead and wounded behind. I brought out my radioman.

They flushed us down to a river bank where we tried to fight them off. They cut us off between our lines at the riverbank so we couldn't get down that way. I took a rifle and beat my way through the ice on the river's edge. About 18 of us tried to cross the river and go down the other side. We started and got almost across when they caught us in the river. We had to swim. Only six of us got out. There was ice on both sides of the river and it was cold, but I don't remember it being cold. I was just too busy. I was trying to carry Fridel and the radio when the radio took a burst. I just dumped it in the river. I was still carrying my radioman out. Actually, I wasn't carrying him--he was just hanging on to me in the river while I was trying to fight. We finally got close enough to our line to where the people manning the outpost could take the enemy under fire. We came back up on the river bank and out of the water. One of the other wounded men helped Fridel into our line.

I was pretty well messed up when I came out of the water, but I had to go back about 700-800 yards to the mortar platoon and get another radioman. I went back to the platoon that night, got a hot meal, and took a bath to get all the mud and stuff off of me. The next morning I had some breakfast at the mortar platoon and then headed back up to the line with my new radioman, a boy named Stanley Smith. It was Christmas Day, but all days were the same on the front line. A couple of weeks later, Smith was wounded.

From Christmas Day of 1951 until January 12 of 1952, I continued to call fire in on the enemy during the daytime. When there was activity in a certain concentration I called in fire missions on the enemy at night, too. The whole time I was in Korea I identified myself in fire missions as "Cablegram Roger 7." Those call numbers identified me in fire missions so the unit would know it was me. If the Chinese knew our call signs, they might call fire in on us. So we tried to come up with letter and number combinations that were hard for them to understand and pronounce.

During this time company commanders offered me the rank of Master Sergeant if I would take a platoon. I was a corporal at the time. My regimental commander was always trying to get me to take a battlefield commission because he knew that I fought without fear. I never got mentally messed up in Korea. I had too much responsibility. The commander thought that I was absolutely fearless because I was always grinning. But I turned their offers for higher rank down because I liked what I was doing as a forward observer. If I was in charge of a platoon, I would have had a whole bunch of people under my care. I would have been responsible for taking care of them (their food, their ammunition, getting them up, everything about them). And maybe every once in a while I might get to shoot at something. As a forward observer, I was always blowing something up, and I liked it.

I carried an M-2 carbine and I generally also carried at least a fragmentation and a white phosphorus grenade. I liked white phosphorus because putting white phosphorus on the enemy and setting them on fire took their mind off of us. I used a lot of white phosphorus. For the most part I got my ammunition when I got a chance to go back into my platoon for more maps or whatever I needed for my fire direction center. They had a mess tent down there and I would run down there to get some onions to chop up and put in C-rations to change the taste of them. I also always got two or three new batteries for my radios. I would get maybe one or two cases of hand grenades to take up to my bunker when the line was stable. I also always gathered up a box of 15 and 30-round magazines for my carbine. I liked a lot of ammunition on me. I liked to shoot a lot. If the enemy was around, I would shoot like hell--throw grenades like hell. The more I hit them, the less chance they had of hitting us.

Again, for me, being in combat was a responsibility. I was responsible for other men's lives--for protecting lives and for taking other lives. I didn't know the names of the young people I was trying to protect. They were just young soldiers. They knew me, though. This one guy come back one day after a real bad thing where the outpost got hit and he said, “Are you the forward observer, heavy mortar?” When I said yes, he grabbed me and kissed me. He said, “You saved me.” They had had a bad night that night. It was in the middle of December of '51. The enemy hit us all along the line there. They hit the outpost, but I had concentrations around the platoon outpost and I killed a lot of them.

I told those people, "All you've got to do is remember that this is concentration so and so, concentration so and so, concentration so and so. If you hear a noise in that particular area, all you've got to do is get in touch with me and say, 'I've got something going on in concentration so and so.'" Within a minute I had fire on them. This one particular night, we had an ambush patrol way out there. It was so foggy we couldn't see our hands in front of our faces and we had a squad out. All of a sudden I could hear firing. We couldn't tell where it was at. This kid called on the radio for somebody to help them. They were lost out there in the fog and the enemy was all around them. I could hear burp guns and grenades going off and burp guns ripping over the radio. This kid was crying. He was scared to death because they had gotten twisted around in the fog and they didn't even know which way to go. When I asked him where he was at, he said he didn't know. I said, “I'm going to put a white phosphorus round way out." Then I said, “Did you see the flash?” When he said no, I dropped the coordinates a hundred yards and said, “Did you see the flash that time?” Again he said no, so I dropped another 50 yards and he saw it that time. I told him that I was going to drop another 50 yards, after which he said he heard it and saw it. I asked him how far out it was from him and he said he thought it looked like it was about 50 yards away. I told him that was on the enemy side and that he should come the other direction. Once he got all lined up, I told him to wait until I told him to move. "When I tell you to move, I want all of you out of there. If you've got wounded, bring them out because right where you're at, folks, I'm going to put some rounds there. That way if the enemy tries to follow you, I'll get them.” When I told him to start moving, they did. When they had gone about 25 yards he called in and told me. I got on my radio and said, “Drop 50.” When they got out of range, we dropped our coordinates to where they had just been. I just kept dropping 25 yards behind those guys so the enemy couldn't close in behind them.

At the same time I was doing this, I got a call from the outpost. They said, “We've got noise around the outpost.” When they told me that it was at concentration so and so, I put a gun on it. The Chinese were firing up a storm, hitting the outpost hard. I had mortar rounds all over the place. The front line went straight across the valley and then there was a high ridge like a ringer sticking out toward the enemy. My observation post was way back and out on the end of the finger with a little outpost out in front of me. I was actually out in enemy territory. The high ground was my observation post. I thought to myself, “If they're hitting them, they're going to hit me,” so I slipped out. I could hear them coming through the barbed wire. I had my radio on and kept listening to what was going on around me. As I was listening, I could hear them coming through the barbed wire in front of me until all at once, I could hear them crawling around in front of me. They had gotten through the barbed wire. I started rolling hand grenades toward them, not much further than a couple of feet. Then I ducked down in the trench trying to get them away from me. I threw a couple of cases of grenades that night in between dropping fire on them, moving that lost squad back, and keeping the outpost covered. I was doing three different things at the same time. It was difficult keeping my head on that one. The guy who kissed me was one that came off the outpost. The Chinese had cut through the barbed wire right in front of him. That night I knew I made a difference. I made a difference most of the time. I was pretty well known. Everybody knew my name and that I was a forward observer.

They sent another patrol out shortly after New Years Day 1952. That time out they were sent around a mountain called Old Papasan. So as not to weaken the line, they never sent people off the line on this type of patrol. Instead, a reinforced rifle platoon of Company B came up from reserve and went out to the right and behind the mountain. They were going to be in my area of responsibility and I was supposed to cover for them when they came out. The Chinese was trying to keep warm that winter just like we were, and behind Papasan they had built a winter installation of bunkers. The reinforced rifle platoon was sent out to hit quick, blow up those enemy bunkers, capture and kill the enemy, and do as much damage as they could. They got hit behind Old Papasan. We could hear the shooting, but there wasn't anything we could do about it. Nobody ever came out.

Soon after that I was assigned to Love Company of the 38th Infantry Regiment. On January 12, 1952, Love Company got the nod to form a raiding party to take Hill 472 (its elevation was 472 meters high) and destroy the winter installations there. They had moved up into my area the night before and the next day we were escorted out through our barbed wire into no man's land. Since I was the forward observer assigned to L Company, I went with them behind enemy lines. Instead of sneaking up on them at night, we did it in daylight. We were supposed to go out at night, but we were slowed down for various reasons and delays. Moving out in the early daylight was a screw-up as far as I was concerned. It was kind of stupid considering they could see us coming for miles. We dropped off a platoon in front of them to raise a lot of ruckus there and make them think we were coming up that way. The rest of the company swung around and hit the back of the mountain. It took us quite a while to get back there.

We had trouble right from the start. I had to go to the briefing and our S-2 said there was maybe a platoon of Chinese on the mountain--maybe less. I listened to him for a while and put up my hand. The regimental commander said, "What do you want, Rosser?" I told him, "What this colonel is saying isn't true, Sir. There's a lot of people up on Hill 472. That's a major fortification up there. It's at least in battalion strength up there. I was with I Company when it got tore up. They wiped us out and you know it. The Chinese came off of 472." I kept insisting that it was a large group until he finally told me to shut up. They didn't want to hear it. The regimental commander generally went with what his staff told him, but I knew better. His staff didn't go out there, I went out there. I knew what was out there, but he wouldn't listen to me.

So we went up there. Of the guys that hit the front of the mountain, nine men lived--and they were all wounded. The platoon sergeant was killed and they had to leave him laying right on the Chinese trench. I blew his body up later because we couldn't get to him. It was making everybody nervous seeing him lay out there frozen. The company commander asked me if I could do something about it and I told him I would take care of it. I blew up his body and scattered his remains all over about a hundred yards. Later I notified Graves Registration. They had him listed as missing, but I told them, "He isn't missing. He's just scattered everywhere."

By the time we started up the back of the mountain fighting our way through the trenches and bunkers, we had lost half the company. By the time we got within assaulting position of the top, there were only 35 of us left out of the 170 we had started with. All of the officers were down, including the artillery forward observer. He got hit in the shoulder. The company commander got hit in the face. All platoon leaders were gone. All the sergeants were gone. There was just a handful of this and that left. I had to fire all over the damned place. We were getting direct, point blank fire from 76 high velocities from all over. I hit them with mortar fire, but they just pulled back in a bunker. As soon as we stopped firing, they came out again and fired at us. We were getting heavy and light mortar fire all over us, as well as heavy machine gun fire at point blank range. I got on the damned radio and called back to the regimental commander on his frequency. I told him who I was--Cablegram Roger 7--and that Love Company was down to about 35 effectives, which meant that was how many were left that were still able to fight, counting the walking wounded. I also told him that we were running short on ammunition. “Request orders.”

He wanted to talk to an officer so I dragged my radio over to the company commander. It was 20 below zero and he had frozen blood all over him. I gave him my radio and told him that the colonel wanted to talk to him. The colonel told him to reorganize and make one final attempt to take our objective. The captain said, “Yes, Sir” and handed the mike back to me. He looked up the mountain and he got this real hopeless look on his face. I was laying right next to him in front of him watching him. I should have shut my mouth, but instead I said to him, “I'll take them up for you, Captain.” He asked me how I was going to do it and I told him, “I'm going straight in shooting, Captain. That's the only chance we've got.” He said to me, “You know you're not going to make it, don't you?” I told him, “Well, we'll try.”

I went over and got all of his men that were left and told them, “We're going to hit them. We're going to go straight in shooting, get in the trenches, and give them hell. If we can get into the trenches, we've got a good chance. Are you all with me?” They said, “Yeh, we're with you.” I told them what to do. “Remember, when I move, all you've got to do is follow me. When I move, you do what I do. You won't have any trouble knowing which direction you've got to go because I'll be leading you up.” I got up in front of them and said, “Okay, let's go.” I jumped up shooting and they did the same. We threw some marching power out for two or three steps just to pin them down in front of us, and then we started running up the mountain through the crusty snow. We only had about 40 yards to go before we got to the enemy. I started running toward them, firing as I went--the old carbine just nicking at the top of the trench ahead of me. I never even looked back until I got to the dirt from the trench. While I was changing magazines, I stopped and looked back. That's when I realized that I was by myself. The other guys were laying all over the mountain where they had gotten hit. That machine gun and mortar fire had just cut them to pieces.

So there I was up on top of this mountain all by myself with the others wounded and the others who weren't wounded trying to break through to get to me. The enemy was only about five or six feet away from us. In the split second that thoughts go through your mind in a life or death situation, I got to thinking, “Well, Ron Rosser. You've come a long way to get here. You might as well make it pay.” So I let out a war whoop like a wild Apache Indian and jumped in the trench with the Chinese. I took out the first bunker with a burst of gunfire. There was a man in front of me and one behind me. I stuck my carbine in the ear of one of them and blew his other ear off. Then I spun around and got the guy behind me in the neck. He dropped his burp gun, grabbed me by the leg and tried to tackle me, but I beat him off of me and shot him in the chest. I think I got him in the heart. Anyhow, he was gone and I started going for more. I finally had gotten what I had always wanted. It was just me and the Chinese. My dream had come true. The thought of my brother crossed my mind. This was for him this time, but I didn't spend a lot of time thinking about it. I remember thinking about it for a split second, then I was too busy. I was hitting them fast, going straight in to them.

They were spinning around trying to shoot me. The burp guns were going off right in my face, but I was killing them before they could do anything. I had a 30-round magazine, but when they were so close I couldn't shoot them, I just beat them. I beat two of them to death with my rifle. I sunk the butt of my carbine deep into one guy's head. I butt-stroked them. When I finally got to the end of the trench, there were two more Chinese--a wounded man and another one. They went into their machine gun bunker because I had flanked it. There were already a whole bunch of Chinese in there. (They had big machine gun bunkers.) I couldn't go in after them, so I knew I needed a grenade.

Before I had jumped off, I had found a white phosphorus grenade lying right in front of me. I looked at it two or three times and then I finally just reached down and stuck it inside of my jacket. So when I got up there and needed a grenade, I remembered it. I reached inside my jacket, got the grenade, and pulled the pin. I crawled up on top of the bunker, kicked the spoon, reached down and held it a couple of seconds, and then rolled it in the door of the bunker. There was a lot of screaming going on. A couple of them crawled out, but they were on fire. I mean, they were burnt badly. I was still on top of the bunker when they came out the door, so I shot them in the head point blank. I put them out of their misery. I should have let them burn. I let the rest of them burn. They were in there screaming, and then the screaming stopped.

I hollered for the guys to come up and help me. I saw some of the guys starting to move and I jumped back into the trench and went around the corner. There came about 35 Chinese at me and I knew I was in trouble again. At first I thought about running and getting the hell out of there. I knew that if I ran, they would chase me. If I tried to hold there, I knew they would just flank me and grenade me. So down the trench I ran toward them, firing as I went. One of them lowered his burp gun and started shooting point blank at me. I could feel the bullets tugging at my clothes, but I never got hit. He couldn't believe that I was still coming. He got scared and he turned around and tried to get away. He ran into the guy behind him and he was trying to claw his way around him. The other guy was trying to shoot me, and others were throwing hand grenades at me. They were going off all around me but I just ignored them.

When the one tried to claw his way around the other one, all at once the whole bunch of them turned and started running away from me. I just stopped and started shooting them in the back of the head. They made a turn in the trench. I saw their heads bobbing as they headed for two big bunkers, so I jumped out of the trench and cut them off. I got ahead of them in front of the bunkers. Some of them ran right up to me trying to get into the bunker. I shot three or four of them before they got inside. I didn't have any grenades so there wasn't anything I could do about it. I started running out of ammunition so I started working my way back to the first trench.

I jumped out of the trench and some kid ran right up beside of me. I don't know where he came from, but a Chinaman raised up and fired a burst right point blank at us. He just almost tore the kid's arm clear off, but he missed me. The kid fell over and I asked him if he thought he could get out of there. He said, “I think so.” He grabbed his arm and started down toward safety. Another kid ran up beside me and a grenade went off between us and got him. I just picked him up and started walking down the mountain because I didn't have any more ammunition. The Chinese were closing in behind me, jumping out of the trenches, shooting at me and trying to bayonet me. There wasn't anything I could do about it because I had this kid on my shoulder. I was pretty powerful back in those days. I could carry the other guy pretty easily.

I started down the mountain about 40 yards under minimum cover and the Chinese were jumping out of the trench trying to get at me. They were still trying to stick me and everything else. An artillery forward observer (James Blackman) had lost his radioman, his radio, and his sergeant. He grabbed an M-1 rifle and ran out in the open, knocking Chinese down all around me. He was flattening them out. I started down the hill and I got to laughing because they were trying to get me and he was getting them. I came walking by him laughing. He stopped and said, “Soldier, what's your name?” He knew I was the FO of Heavy Mortar Company, but he didn't know my name, or at least he didn't remember it. I said, “Hell, my name is Rosser.” He asked me if I knew what the hell I was doing and I replied, “Yes Sir. I'm killing these varmints as fast as I can, but I'm out of ammo. I've got to get me some ammo.”

I put a compress on the kid that I had carried down the mountain because he had a chest wound. I put a tourniquet on the arm of the kid who got his arm hurt while he was trying to help me after I got out of the trench. It stopped him from bleeding to death. I tied his arm to his stomach with a canvas machine gun belt so it wouldn't be flopping around and I told him, “We'll get you out of here in a little bit, son.” I went around to the dead and wounded and started gathering ammunition--especially all the grenades I could carry, and some carbine ammunition. I got some magazines off of my radio man. He was already wounded but when I asked him to give me some ammo, he said he might need it. I told him that I needed it worse than he did and for him to give me the ammo.

I threw a round in the chamber, loaded up what magazines I could find, and slung a rifle on my shoulder. I took a hand grenade in each hand, pulled the pin, held the spoons down, and turned around and started back up the mountain. This lieutenant was still banging away. (James Blackman received a Distinguished Service Cross for what he did that day.) When I got up to him, I tapped him on the shoulder. Still holding a grenade in both hands I said, “I'll see you later, Lieutenant,” and started up the mountain.

The Chinese were laying over the trench waiting for me to come in closer. I don't know why they didn't just shoot me--I was by myself. Instead, they were just watching me. All at once I saw one of them raise up to shoot me, so I threw my first grenade. Instead of shooting me, he and all the rest of them looked up to see where the grenade was going. It went right into the trench with them and got some of them. There was a lot of confusion and wounded men laying around. As I got closer to the trench, I just kicked the spoon on the other one, held it a couple of seconds, and dropped it on the wounded as I went by. My plan was to get those two big bunkers filled with Chinese, so I was after the varmints. I was shooting my way through a bunch of Chinese when one of them threw a hand grenade at me and I got hit in the shoulder. It was just a little piece of shrapnel that hit the top of my shoulder, but it was just enough to make me mad. I chased him through about twenty screaming and hollering Chinese. They actually got out of the way while I chased him down and shot him. I shot my way to the two big bunkers where the Chinese were running into the door. Some of them were trying to get out while the others were trying to get in because they knew they should never get caught in a bunker.

I went up to the first bunker, stuck my carbine right in the door, fired a burst in there, and chased them away from the door. I was carrying a large number of hand grenades all over me. They were stuck in my jacket and in my pockets. I don't remember the exact number I had, but it was at least a dozen or more. I took a white phosphorus hand grenade, pulled the pin, kicked the spoon, held it a couple of seconds, and threw it in the door. A lot of noise started coming out of there. I mean they were screaming like hell. I threw in two frag grenades and they stopped screaming.

There was another bunker on the other side of the trench. They were trying to get out of that door so I fired a burst at them and chased them back in. I backed up to the door, pulled out another white phosphorus grenade, and just flipped it in the door. They started screaming so I threw another frag in and again they stopped. I looked around and there were Chinese coming at me from every damned direction—I mean every direction. I jumped out of the trench because I couldn't fight from there with them coming at me from everywhere. I grabbed another white phosphorus grenade, pulled the pin, kicked the spoon, held it a couple of seconds, and threw it up in the air above me kind of at an angle away from me. When it went off, it came down like rain. I got an air burst right on top of the Chinese and me. I was out on the peripheral, dodging the streams as they came down on me. They came down like smoking rain. As soon as most of it hit the ground, I took off running through it. When I came out the other side, there were three or four Chinese standing there trying to figure out what was going on. I got a couple of them before they could get out of my way.

I was running down the trench right beside the Chinese. They were trying to get away from me, their heads just bobbing in the trench. I was shooting as I was running by them. I would see a group up there and I would throw a hand grenade until I finally ran out of them. I was starting to run out of ammunition and had to fight my way back again to the first trench. The Chinese were still coming at me. My clip was empty, but I didn't know it until I reached for it and discovered that I didn't have another round of ammunition left. I also had no grenades. I was standing in the trench when a Chinaman ran right up in front of me--right on top of me at the edge of the trench. He had a submachine gun and started shooting at me. I didn't have any ammunition left, but he didn't know it. I threw my carbine up in his face and for just about a split second we looked at each other. Then I screamed right in his face just as loud as I could. He let out a "woooo" and turned and ran. I started laughing again because I had bluffed him.

I got out, picked up another wounded kid, and started walking down the hill with him. Blackman was still banging away with that M-1 rifle. I don't know where he was getting all of his ammunition—off the dead and wounded, I guess. I came walking and laughing by him with that kid on my shoulder and he was just shaking his head. The kids were looking at me like they couldn't believe it. I think they thought I was hell on wheels. The wounded and some of the guys that weren't wounded were looking at me real funny. Before it was all over, everybody was wounded or dead. I started patching up wounded men as best as I could because all the medics were dead. The best I could do was just put another compress on them to try to slow the bleeding down.

The fighting wasn't over yet--it was still going. I had gotten some more carbine ammunition, but I saw that the Chinese were starting to build up again on top of the mountain. I knew that they were going to hit us again. Everybody was wounded. I had already been hit twice--the second time was in my hand. I went around to the dead and wounded and found as many grenades as I could. I ran back up the hill again clear up to the trench. I started throwing hand grenades and scattered their butts. This was my second time up there, banging away at everybody. By that time most of the Chinese who were still alive knew me and they were scared of me because they couldn't stop me. Grenades were going off right beside me. I had just shot a Chinaman in the trench when a grenade went off against my foot. Instead of blowing my legs off, it blew part of the heel off my boot. The grenade came down, hit me right on the side, and dropped against my foot. It come in hot so I dove across this Chinese guy. The guy thought he got me. When I bounced back up, he couldn't get down fast enough so I gave him what was left of a clip--close in and right to the stomach.

Finally after I threw the grenades a third time, scattering the Chinese, I told the company commander, “Captain, you'd better get your people out of here or you're going to lose everybody. By then he was just helpless so he asked me if I could get them out. I told him I would. I went over to the walking wounded and told them that we were going to leave this place. I said, “All you guys who can still fight get all the ammunition you can find.” They started gathering up the ammunition and I said, “Okay, we're going to hold right here, boys, while we get the rest of the men out of here.” I started a daisy chain of wounded down the mountain. The regiment had sent out four tanks that managed to get below us, but they couldn't get any farther because they were taking heavy mortar and artillery fire.

The Air Force came in and started hitting all around us. They were dropping 500-pound bombs all over the dang place. I made everybody that could walk take a dead or wounded man with him and carry him down to the tanks. Some of the guys from I&R Platoon helped us carry the dead and wounded out. We held and there were still wounded men laying all over the place. The dead and wounded were between us and the Chinese. Two or three other guys and I started running out there getting them. The Chinese were shooting us at point blank. One kid was laying just a couple of feet from some Chinese who were laying right underneath the top of the trench. They were shooting over him. He had been hit in the chest a couple of places. He was watching me as I dragged the guys out. He probably figured he was never going to get out but I finally went over to him, got him by the back of the neck, and said, “Come on, boy. Let's get the hell out of here.” I started dragging him down the mountain. He later told me that the most scared he was that day was when I was dragging him. He was facing the enemy and they were raising up shooting point blank at both of us. Neither one of us got hit again. I don't know why.