"I am left with an indelible memory of a Japanese girl…. Let the world know how a vicious war influenced and touched two young people caught up in events they could not understand."

- Chris Sarno

[Editor’s Note: The following memoir was compiled and written by Lynnita Jean Brown from an interview with Chris Sarno that was conducted at the 1st Marine Division Association Reunion in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1999. Additional comments by Chris Sarno were provided for his memoir from a tape recording which he sent to a former Army rifle platoon leader in Korea, Pete Wood. They also came from voluminous correspondences for clarification between Chris and Lynnita while the Question/Answer interview was being transformed into a readable manuscript. Some photographs of tanks are published in this memoir with the permission and through the courtesy of Donald R. Gagnon, editor of the Marine Corps Tankers Association newsletter. No portion of this interview may be downloaded or copied without the express permission of the Korean War Educator. Mr. Sarno died August 06, 2014 from complications associated with diabetes.]

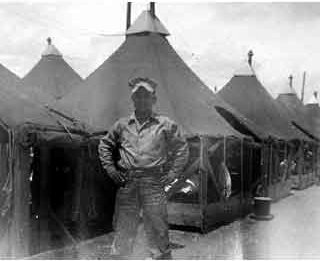

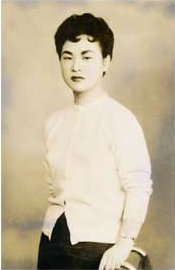

Chris Sarno is pictured above, thinking of "the girl I should have married." For Chris, this Japanese beauty possessed a "traditional inherent feminine quality known only to Japanese women since time immemorial." Yoshiko and Chris loved each other, but they never married due to racial ideologies that were not compatible in the 1950s.

Chris Sarno is filled with pride in the fact that he served as a combat Marine in a tank company in the Korean War. There is also an interesting twist to his war story. On R&R, he met a beautiful Japanese business girl. Eventually, he fell in love with her. In the wake of war and its aftermath, two post-war (World War II and Korea) young people from different cultures were thrown together. Each needed the other for different reasons. With only immaturity to guide them through social and racial barriers, they could not resolve their differences. The life of one ultimately ended in tragedy. Time marched on with bittersweet memories for the other.

To understand how different cultures can clash, one need only look as far back as the lives of Chris Sarno’s parents, Christopher John and Florence Shanahan Sarno. Florence Shanahan grew up in Medford, and during her senior year at Medford High, she was courted by Christopher John Sarno, who was a sophomore. He was a three-year All-State high school athlete in football, basketball, and baseball. Chris and Florence, who were very popular, did all the dances and enjoyed the "roaring twenties." After high school, Chris attended Fordham University in New York City. At that time, Fordham was a prestigious Jesuit college. Sarno, who excelled at all three sports in his freshman year, was looked upon to be Fordham’s up and coming star for the future. In turn, he loved the regimentation of a Jesuit education: morning Mass and a structured daily Catholic regimentation. His future seemed bright on a professional level as an athlete in New York City.

In the summer, he returned to Medford, where he continued to court his Irish sweetheart. This courtship was one of much chagrin to both of their families. Florence came from an Irish clan that abhorred Italians, and the Sarno family was just as parochial in their dislike of the Irish. However, Florence and Chris were passionately in love despite both families’ unrest, and they decided to marry. Once the wedding date was set, Chris’s parents threw all of his clothing out in the yard. Nevertheless, before his sophomore year, Christopher John Sarno married Florence. The couple went to housekeeping in New York City, residing in the Rose Hill area near campus. Looking back on his childhood, their son—the subject of this Korean War memoir--noted that the discord between his Irish/Italian heritage was beyond his and his siblings’ control. "My mother never visited my father’s house after they married—it was that bitter," he said. "The Irish were brazenly outspoken, while I saw how quiet and gentle the Italians were. With all due respect to the intermarriage between Irish and Italians, that holy union produced the most beautiful babies the Vatican smilingly looked upon as the vanguard of the propagation of the Roman Catholic Church. Indeed, the Vatican has always been the firm, and now respected conduit that holds the Irish and Italian Americans forevermore. I was virulently brought up as Irish-Catholic. The US Marine Corps is overloaded with good Marines from this fiery and passionate bloodline."

In the summer, he returned to Medford, where he continued to court his Irish sweetheart. This courtship was one of much chagrin to both of their families. Florence came from an Irish clan that abhorred Italians, and the Sarno family was just as parochial in their dislike of the Irish. However, Florence and Chris were passionately in love despite both families’ unrest, and they decided to marry. Once the wedding date was set, Chris’s parents threw all of his clothing out in the yard. Nevertheless, before his sophomore year, Christopher John Sarno married Florence. The couple went to housekeeping in New York City, residing in the Rose Hill area near campus. Looking back on his childhood, their son—the subject of this Korean War memoir--noted that the discord between his Irish/Italian heritage was beyond his and his siblings’ control. "My mother never visited my father’s house after they married—it was that bitter," he said. "The Irish were brazenly outspoken, while I saw how quiet and gentle the Italians were. With all due respect to the intermarriage between Irish and Italians, that holy union produced the most beautiful babies the Vatican smilingly looked upon as the vanguard of the propagation of the Roman Catholic Church. Indeed, the Vatican has always been the firm, and now respected conduit that holds the Irish and Italian Americans forevermore. I was virulently brought up as Irish-Catholic. The US Marine Corps is overloaded with good Marines from this fiery and passionate bloodline."

Christopher Edward Sarno was born in the Jewish Memorial Hospital in New York, New York, on January 25, 1932. One of seven children, he was known by his family and friends as "Junior" from day one throughout his childhood and youth. (As of the day he arrived home from Korea, however, family and friends referred to him as Chris.) Not long after he was born, his father was called into the chancellor’s office at Fordham during the Spring of 1932. He was told that he was being dismissed from Fordham for being married. "In those unyielding days," explained Chris and Florence’s son, "you had to be single to attend a Jesuit University. My father bent the rules, and someone ratted him out. I truly believe this entry in his life had later ramifications for his being a wage earner. He could have been someone in sports—people all over Medford marveled at my Dad’s prowess on the gridiron—but he was left to mediocrity for the remainder of his life." In 1942, Mr. Sarno became a regular police officer on the Medford City police force. He made a career as a police officer, serving honorably on the force for 40 years.

Although the elder Sarno worked and always had a job, there were times when the bill collectors knocked at the door. "My mother was a fighter to provide for her brood," recalled Chris "Junior" Sarno. "She was fearless. She did yeoman tasks to give us tight family ties. My mother was a Trojan in running the house, eventually going to work during the World War Two years, making radios for the US Navy. During the war, American women were recruited to work outside the home structure for the first time. Mom loved it, and she made decent wages, too," said Sarno.

Chris "Junior" Sarno attended Medford Public Schools. His boyhood years (1942-45) were also World War II years. "We were inoculated every Saturday and Sunday with patriotic movies even after the A-bomb drops," Sarno recalled. "No one, and I repeat, no one, ever would ‘play’ a Jap because of our hatred through constant radio war stories and those fascinating movies which gave Japan all the worst of it. I recall one humid afternoon when torrential rains came. I was with my father and brother Bud, and we were standing on the front porch. I clearly remember watching a total rain-out hitting the street, and I said, ‘I wish every raindrop was a bomb over Japan.’ It had to be in 1944. I never thought World War II would end. My mindset was forming about the Japs in particular." And there were movies that influenced the minds of young boys growing up in the war years. "There was another movie with Robert Ryan in a Jap jail and him looking forlornly up at bars that only showed the sky," recalled Sarno. "I felt for him—being in that godforsaken country, about to die, and no one able to save him. Little did I realize that someday I would be in the occupation of racist Japan, then under a totally awakening environment."

While some of the boys in Chris’ neighborhood were Boy Scouts, he was not. "They held meetings in a Protestant church basement," he said. "Because I was Catholic, it was a mortal sin to be in a Protestant church." Instead, he delivered newspapers in the afternoon when he was about 14 or 15 years old. He delivered the Boston Post for 16 cents a week. He got 22 cents a week for delivering the Boston Herald, Boston Record-American, and the Boston Traveler. "I had 60 homes to hit," Sarno recalled. "I got $1.00 from the news office and I made $4.00 in tips. I gave the $4.00 to my mother, and the rest was for pogie-bait [candy]. I was now helping out with the general welfare of our house/family. A year later, my brother Bud hawked papers. We eventually had a 5 a.m.-7 a.m. route of 120 houses. We split the nearby route. Tips went up to $8.00, and we had $2.00 each for mad money. The rest was given to our mother, and we never bitched one moment because we gave it to her. We were happy to be supports to our folks. Rationing was very Spartan all during the war." According to Sarno, the paper routes were very hard, and because of them, he and his brother lost 44 school days in 1948. Brother Bud was an A and B student. Chris’s grades were not that high. "I hated school," he said.

At age 16, Chris Sarno and his brother gave up their paper routes for more lucrative work. Their mother was acquainted with the general manager of Boston’s biggest theater, the RKO-Keith Memorial. There was no television yet, so movies were still the king of entertainment. "As part-time ushers six days or nights a week, we earned 47 cents per hour," said Sarno. "Movies educated me about the world outside of the USA. I loved the newsreels." One of the perks of his ushering job was the fact that the ushers in other movie houses around the city let him and his brother see for free all the movies shown in Boston.

By far, the RKO-Keith Memorial was the classiest movie theater in town. "I remember working with holes in my shoes for a long while," said Sarno. But the holes didn’t matter because the RKO-Keith was carpeted throughout. Ushers wore sharp-looking summer and winter uniforms that accented the good looks of the theater interior. Thousands of moviegoers mingled through the theater every week, especially on Saturday and Sunday.

Outside of the movie house, the Sarno brothers were active participants in local sports. "I was always looking to play the seasonal games of sport, and I threw all my passion into my performance, be it baseball, basketball, or outdoor ice hockey," Sarno said. "It was my goal to be like my famous Dad in athletics. The smell of the gridiron was like being in heaven for me." Unfortunately, Chris was small in stature and weight. This combination was to put an end to his dream to be on the Medford Varsity football team his sophomore year. His self-esteem took a spiral dive, and it was reflected in poor academic grades.

A year later, he rallied out of the academic nose dive, and achieved decent marks in high school college course work. He played varsity baseball and hockey his junior/senior years. "In 1949," he said, "we won the City League Baseball Championship with a 24-3 record and runoff 14 straight league victories as champs. Ten teammates were All-Star selections. I was best shortstop in City that year." Sundays during baseball playoffs, he was allowed to play ball for a few hours in the afternoon before rushing back to his job at Keith Memorial. In the heat of August, he kept a hectic schedule. "After the game, I rushed home, gulped down a huge bowl of cooked white rice mixed with crushed pineapple and real whipped cream, and then I took off like a raped ape to catch a trolley car to Keith Memorial," he recalled. "Then I worked from 5 p.m. until midnight—for 47 cents an hour. My calves hurt standing up there, but I loved my baseball."

After 1949, Chris Sarno’s attention turned from sports to romance. "In April of 1950," he said, "I got a whopping increase from 47.5 cents an hour to 50 cents, and I was made captain of the twenty-plus usher cadre." He worked the day shift, and also supervised three usherettes. He was infatuated that summer and autumn by a tall Irish usherette named Mary. "She wanted me to buy a car," Sarno said, "so I quit work at K-Memorial to the chagrin of my mother and the managers, and quickly got hired at New England Bedding company, which specialized in lounge furnishings. I was hired in September of 1950 at 75 cents an hour at general factory labor. It was only a quarter mile walk from my house. I liked the new work plus overtime. At times I made close to $80 a week with salary and piece work. I was on my way to a $300 used car." When the war broke out in Korea, Sarno traded in his assembly-line civilian job for a front-line military job in the Marine Corps. "In 1951, the Navy paid us nine cents an hour, 24 hours a day," Sarno said. "They fed us, clothed us, and took care of us in sick bay at the expense of the government. Talk about slave labor!."

For Chris Sarno and so many other young men his age, the police action that had broken out in Korea earlier that summer was the furthest thing from his mind when it first erupted. "Besides," he said, "we had General MacArthur and the A-bomb. Who was to worry? I was deeply in love with Mary, and she was my world now." But the world as the young Massachusetts boy knew it was about to change dramatically. He might have been in love, but he was also 18 years old—draft age. When President Truman declared a national emergency (war), he also accelerated the drafting of all men in the age bracket of 18 to 25. War reports coming from Korea were really bad, Sarno recalled. "I refused to be drafted. I decided to volunteer for the Marine Corps."

At that time, there were no draftees in the Marine Corps. "There was no way I was going into the Army," Chris said. "I always considered the Marines as elite. And…they go to war. You want combat? The Marines will make sure they’ll find you combat. With a war going on, that’s what I asked for—FMF—Fleet Marine Force—going to Korea."

His girlfriend Mary was not happy with the news, so Chris tried to soften the blow of his imminent departure by spending his last $12.00 on a night lounging coat for Mary’s Christmas gift that year. Although Mary shed a few tears over the news that the man who had lavished his affection and gifts on her was about to depart for military duty, she quickly found a new boyfriend to replace the one who had left the Boston area to serve his country. "I asked a friend of mine to keep an eye out for Mary, as he was an usher at the Keith Memorial where Mary worked," Sarno said. "I wrote to her first, but Mary never wrote one letter to me while I was in boot camp. I heard later that my pal and Mary were a hot item. Because of her sudden change of heart, it took me a long time to trust a girl. I loved a new mistress instead—the United States Marine Corps."

Sarno’s decision to join the Marine Corps came out of the blue, he said. Two of his uncles had served in World War II—one in the Pacific and one in Europe, but both were Army veterans. "Being of that age of not knowing what I wanted to do," Sarno said, "going into the Armed Forces at that time was very exciting. It wasn’t patriotism totally. It was just adventure. I always wanted to be a pilot, but didn’t have the education for it. But when the time came to go to war, I all of the sudden decided it was the Marines. My mother screamed when she found out that I had signed the papers to enlist. She didn’t want me to get killed. But I was of age to enlist without a parent’s permission." The date was December 10, 1950. Although it was not his intention to cause emotional distress to his mother, Chris Sarno held firm to his decision to join. "It was my time, my war, and I was going," he said. "I wanted to go."

In order to go, however, he had to overcome some technical difficulties with regards to his health. On his mother’s Irish side of the family, there was a long history of diabetes. When he was taking the physical for entry into the Marine Corps, the doctor asked him about diabetes in the family. When the doctor found out that there was diabetes on the Shanahan side of Sarno’s family, it caused a glitch in Sarno’s enlistment efforts. "He didn’t reject me," Sarno said, "but the physician told me I had to go see a civilian doctor and bring medical proof back that I didn’t have diabetes." Even his family doctor tried to talk Chris out of going through with his plans to join the Marine Corps. "This was when the doctors used to come to the house," explained Chris. "They knew all the families in my ethnic Irish/Italian neighborhood. It was a very close-knit group of people in the neighborhood, and he knew my family very well. He didn’t try to coerce me, he just said that I should think it over because I was just a kid. But I said I was old enough. Whether I was a kid or not, I was going. There was a war going on and I was going to go into the Marines." The civilian doctor gave his determined young patient medical clearance, and on December 20, Chris Sarno was accepted into the Marine Corps.

The next day, he was taken down to South Station in Boston with the other of only two enlistees from the Boston area—Billy Evans from Amesbury, Massachusetts. Chris Sarno eventually went to Korea, but Billy went to Cooks and Baker School in the Corps, and never made it to Korea. "It was Christmas time," recalled Sarno, "but that was not on my mind at all. This would be the very first time in my young life that I would be on my very own. I was anxious, but wide-eyed and wondering about the unknown. Billy Evans and I were the only two leaving Boston for Yemasse, South Carolina, wherever the hell that was." Sarno had never ridden in a Pullman car before, and as the train arrived at Penn Station in New York, the youths from Boston found themselves gaping at the awesome New York City skyline.

"There we picked up ten more enlistees and went on to Philly where another eleven enlistees boarded," Sarno recalled. "We had two regular Marine NCOs in charge, and they treated us like civilians—nice chatter, but they watched us like hawks to make sure that no one went AWOL. We all blended in, bullshitting and sizing each kid up. It was a good bunch, and there were no incidents. Sleeping was great, listening to that ubiquitous clickity-clack of the steel to the rail." When the NCOs awoke the youthful travelers under their charge the next day, Sarno said the scenery had changed to one with tall willowy pine trees with moss hanging from the branches. Using government-issued dining chits, he and the others ate lunch, supper, and now breakfast, served by burly black waiters, in the Pullman dining car. "I had a full order of ham and eggs in Carolina, just like that Al Jolson song," he said. Then, just after lunch, the train stopped. A tiny rusty sign marked their departure point from the Pullman—Yemasse, SC. "I didn’t realize this was our destination," recalled Sarno. "I was in the last car, which was the Club Car, standing there looking out at this poverty-looking whistle stop. I was alone, realizing that it was December, but the weather was real warm with a scrub palm here and there."

One of Chris Sarno’s long-term memories of the Yemasse train station was the sight of a little black child about ten years old, standing between two sets of tracks and looking up at Sarno on the train. "Hey, Yankee man," the child said. "Gimmie a dime, will ya?" Sarno only had a few coins remaining in his pocket. "I remember saying, ‘Get lost,’ he admitted. From now on, the recruit from Boston had bigger things to think about than loose change in his pocket. For now, another Marine sergeant took charge of the fresh batch of raw recruits. "This was a Southern Marine," recalled Sarno. "He looked ugly like a Ukrainian thug. He treated us like shit. Not that we were afraid of him, but he just treated us like we were clowns." Calling his charges "cheap-shit civilians", he herded the recruits into a World War II-style wooden barrack where the boys spent the night. "It was a one-story wooden shack with about 40 racks and a concrete shower room that smelled like creosote," Sarno said. "The supper meal we had was in a ‘Greasy Spoon’ with a white cook/owner and flies all over the interior of the restaurant." He said the menu choice for what was to be their last chit meal while traveling to Parris Island was limited to chunks of chuck beef with gravy over a bed of white Carolina rice.

The barrack was one of about seven little shacks with rusted corrugated aluminum roofs. Sarno recalled that there were some blacks shuffling along, and whites shouting orders on what they were to do. The railroad tracks ran right through the center of the rusted shacks. "Now I realized that this was the piss-poor rural south," he said. "I knew nothing about the South except that they lost the Civil War. I didn’t care about the South. My family never traveled that way. I showered, and we slept with a fire watch post in the barracks."

The next morning, with no breakfast under their belt, the 25 recruits boarded old-fashioned green buses with US Marine Corps markings. Nearing the last leg of their trip, the recruits saw lush palm trees. "I thought to myself how great it was to be seeing these tropical plants for the first time in my life," Sarno said. "I was like a lamb going to the slaughter." When the bus trip came to an end at Port Royal, South Carolina, the recruits had a shocking introduction to their first drill instructor—a Marine dressed in greens and looking sharp. Sarno said, "He walked to the back of the bus silently, turned around, and started yelling, ‘Get the fuck off my bus. All I want to see is assholes and elbows. Get the fuck off my bus on the double! When he started cursing us on the bus, that’s the first time I felt fear. We all bolted for the narrow doorway. It was panic as everyone tried to get out the door at the same time. The doorway was backing us up, and that Marine lunatic was screaming racial slurs like we were shit. We all stumbled out like drunks, and there more DI’s were waiting, screaming profanities I had never heard before. When that first SOB of a DI got onboard the bus, the world of my boyhood exploded out of my young life. Forever!! That’s what I recall vividly. I was in Hell, but within two months I was cloned into a devil-dog that will never give up its grip on me until I die." While the frightened boys made a run for the door, practically crawling over each other to get out, the DI stood at the back of the bus laughing at them. "But we weren’t paying attention to him," recalled Sarno, "we were trying to get the hell out of that bus as fast as we could."

Sarno explained that this initiation into the world of the United States Marine Corps was the beginning of a process in which recruits were shaped to withstand "being ranked upon and not reacting." He said that it had an overall bearing on the bigger picture of being a Marine. "But being civilians," he admitted, "we were just frozen with fear."

The final leg of the journey to that "asylum on the island" as Chris Sarno called it, was a short bus ride to the main gate. "There were palm trees, and it was beautiful," he said. "They stopped the bus and pointed out things. You could see the ocean with running current right behind the main gate. They said, ‘Don’t get any ideas. Once you get on the island, if you don’t like our little home, don’t think you can swim across, because the current will sweep you out. And if the current doesn’t get you, the sharks will.’ That was our entrance to Parris Island."

Back in the 1500s, Parris Island had served as a British penal colony. By 1950, it had become one of only two Marine Corps boot camp training grounds in the United States. Upon Chris’s arrival there, he took quick note of his new environment as the troops were directed to their quarters. He saw scrub palm trees that were smaller than the palm trees found in Florida, long grassy plains just back of a side road, and a huge black-topped area known as "the grinder." There were rows of wooden barracks, but the fourth training battalion that Sarno had been assigned to was quartered in the last of about a half dozen Quonset huts located by the road to the rifle range. There were 89 recruits in Platoon Number 288. "We were all like sardines because there were so many in this Quonset hut, and we didn’t know one from another yet," recalled Sarno. They were warned that there would be no pogie bait (candy), no cigarettes (at least not for a while), no radios, and no newspapers during boot camp training. The new arrivals were now cut off from the outside world. They were to concentrate on learning what it took to be a Marine. The Marine Corps wanted no diversions while the boots went through the transformation from civilian to Marine.

The new boots were put in platoons by size, with the taller guys in the first platoon and the light weights ("feather merchants") in the second platoon. "I happened to be on the end—the very last rank of the feather merchants," recalled Sarno. "The DI said, ‘About face.’ Now I was the lead platoon." The platoon followed the drill instructor’s "forward march" command. "We marched the best we could," said Sarno. "It was pitch black and the DI’s were swearing at us. And then the DI said, ‘left flank.’ I was on the left—I didn’t know what the hell he was saying. He had a rebel voice, and I was just wandering around. He screamed at me to do the left flank, and I didn’t know what left flank meant. So I went to the left casually. He was all over me. I thought, ‘Why the hell did I join this outfit? This guy’s crazy.’" With their first sloppy march behind them and still in civilian clothes, the new recruits ate an evening meal.

After their first meal on Parris Island, they returned to the Quonset hut, and to their beds. Those "beds" were actually steel racks. On each of them were two thin, steel-coiled spring mattresses. Neither bedding in the form of blankets or sheets nor military clothes had yet been issued. "Ten o’clock came, taps were blown, and our dim light went out. We were laying on the mattress still wearing our clothes," Sarno said. "A few minutes later, we heard this scream, ‘Boot 288 outside!’ The fear of God was deep in all of us. The first guy to the wooden door was crushed as we fought like sailors about to drown to get topside." Once outside, the bewildered recruits stood at attention as best as they could. "Now there were three DI’s that we’d never seen before," recalled Sarno. "They were our DI’s, but not our senior DI’s. They were all junior DI’s, and they were the worst of the worst. They wanted to be THE DI. So they got us and they were in our face. They swore at us, calling us everything under the sun. Not touching us—just in our face. I wasn’t scared, but I was bewildered."

The platoon was ordered into the Quonset hut to bring one mattress out. "We went storming back inside," recalled Sarno, "crashing through that wooden opening like rats. Then the DI told us to ‘bring out that mattress.’ So outside we went with the mattress. But then he said, ‘You brought out the wrong mattress. You’re supposed to bring out the bottom mattress.’ So we went back in with the mattress. It was chaos drill, and we were doing it with rapidity. We were not just slowly getting in, we were killing that other guy trying to get through." Sarno said that falling recruits were simply stepped on in the rush to get out the door, and there were mattresses strewn everywhere. "Once everyone came out with a single mattress, the drill instructors demanded that we then go back in and bring out both mattresses instead of just one. That went on for about 30 minutes, and by then we were sweating like greased pigs. The DI got us back into that Quonset hut, and eventually he and the others left us alone so we could get some sleep. We were laying there, and I guess everybody else and I were wondering the same thing—what the hell have I gotten myself into? This place is nuts. But I didn’t want to go home. I was just totally bewildered. This was a whole new world for me, and I didn’t know what the hell was going to happen the next day."

Many of the new recruits had never been on the receiving end of such verbal tirades before, but Sarno said there weren’t any tears. "I can honestly say that I never heard a boot crying. Not one. I’m not saying that we were tough guys, but nobody cried. I will say this, however. A lot of the 89 started to have epileptic fits. We’d be doing something and the guy would just collapse in ranks. That was done by the DI’s purposely to weed out the medical weaklings. Even though you passed the first physical, the DI’s main objective was to pounce on the weaklings—find the weaklings and get on their case something fierce so they would quit and want to go home. They only wanted the mentally tough willing to go through the wall down the road—unhesitatingly." This weeding out process was ongoing throughout the entire two months of boot camp. One day a weakling was there. The next day the "weakest link" was gone. Chris Sarno’s platoon—No. 288--began with 89 boots and graduated with only 69 after the DI’s weeded out the medical weaklings and wannabes.

The boots fell into some semblance of formation for close order drill to get their gear and clothing, minus a weapon, the day after they arrived at Parris Island. The boots went to the island barber shop to be shaved of every strand of hair on their head. Sarno had arrived on the island with a neat, short haircut from his jock years on the playing fields in Boston. On Parris Island, even crew cuts were forbidden, however. He and his fellow recruits were issued World War II-style dungarees and boondockers (a boot that only went up to the ankle). "We were issued clothes and everything else that we needed for official issue," said Sarno, "including a thick paperback book about what a US Marine in or out of boot camp must remember. It helped me understand my new interest in life now—to be a US Marine. It was like a Bible for a Marine to always refer to, but it was the religion of the USMC. I loved it and it helped me tremendously. They call it something else now, but mine was called, ‘The Guide Book for Marines.’."

Each of the new recruits also received a small aluminum pail, toiletries, and a big, hard brush. The pail would become an important part of their life in boot camp, because with it they washed their clothes before hanging them on an open clothes line to dry, and they scrubbed a lot of other things too. Boots were required to keep the Quonset hut spit-shine clean, and there were field days three times a week. Those field days were equivalent to "spring cleaning" in civilian life, only the consequences of "missing a spot" were far more miserable on the boots if the drill instructor happened to find the spot. And if there was a missed spot, the DI would most surely find it. "We were not even thinking of a weapon at this time," Sarno remembered. "I had my hands full just to know close order drill with a formation. But, we did okay. Then they drilled us on the ten general orders."

The ten general orders learned in boot camp were used throughout the Marine Corps in all duty stations to insure attention to duty, respect, and uniformity. They were and are the rules that Marines of all ranks have lived by for decades. "We were ordered to memorize them that day, because the next day we would be questioned," recalled Sarno. "You had to have it exactly right. They questioned us by going through the ranks and randomly choosing one recruit after another to recite a particular order. They wanted the proper response. It was a cram session—cramming to learn them word for word, and it wasn’t fun. But if you missed so much as one word, they got all over you."

The next day, the new boots were taken to Main Side buildings for two days of written tests. "I scored 110 on the General Military Test," recalled Sarno. "Those who got a score of 120 were asked to go to Officer’s School." In the afternoon, the men took a basic radio school test, and many of those who scored high later went on to be in the Communications Section. The recruits were allowed to list their preferences for a military specialty. Chris Sarno’s preferences were tanks or artillery, although he knew very little about either. When making his choice, he said that he just used common sense. As an usher in the Boston movie theater, he used to see numerous documentaries after World War II. "Tanks always caught my fancy with their brutish appearance, speed and fire power," he said.

During one afternoon of testing, he not only happened to chose a preference that sealed his fate as a tanker in Korea, he also had to pass a very unusual psychological test. "I remember that we were asked to draw a side profile of a woman," recalled Sarno. None of the boots knew exactly why they had to do this. The one boot who dared to ask was verbally berated by the DI for so much as questioning "why". Everyone just assumed that the drawing ended up with a Marine Corps psychiatrist. "Self expression does reveal personality pluses and minuses," Sarno noted.

The recruits were expected to passed a rudimentary close order drill in formation before they were issued a weapon. Once that was behind them, they were marched down to the grinder to go to the armory for a weapon. There was no mistaking the group for anything other than the raw recruits they were at the time, Sarno recalled. "We had dungarees with the open blouse never tucked in. We weren’t allowed to wear leggings because we were not considered to be true Marines while we were still in boot camp. Our DI told us that we looked like a bunch of clowns, and that we were a bunch of clowns. They never gave you a compliment. Not once. Any time they opened their mouths to any of us, it was always to say something derogatory."

The armory was a huge aluminum building that housed nothing but M-1 rifles. When the recruits went inside of it for the first time, they were assigned a rifle. "We yelled out the serial number of the rifle," recalled Sarno, "and then we were responsible for that rifle until we left the island. That M-1 rifle weighed 9 ½ pounds. I never saw a weapon in my life, and that thing looked huge to me. I liked it!."

Just as they were getting close order drill down pat, the recruits suddenly had to learn the manual of arms—how to handle a rifle. Sarno admitted that this new training exercise caused him some anxiety in the beginning. "I thought, oh jeez, I’m never going to get this one—using a rifle and using my feet at the same time. Within a week, however, we were looking pretty good. I remember this little DI—the junior DI. He was a son-of-a-bitch. He was a little guy about 5’4". Mean? He sure was. He had a tongue on him that he could lash out at you and you’d swear you were bleeding. He loved being a DI. He would come to various ones of us and command us to do something with the rifle. It so happened that he stopped in front of me and said, ‘Do inspection arms.’ So I went through it and I did inspection arms. But when I came back to rip that bolt down and open the chamber, it opened but I looked at my rear sight and it was missing. For whatever reason, I didn’t have a rear sight. He grabbed the rifle because he was going to inspect it. Sure enough, he said, ‘You f---ing….where’s your rear sight? I told him that I didn’t know. He replied, ‘You don’t know? Are you kidding me? A Jap would kill you in a minute.’ When we got down to the grinder, he broke me out of the formation and told me to go at high port [holding a rifle at a certain position in front of the chest] to the armory and get a new sight."

Sarno said that he ran about a thousand yards at high port, double-timing to the armory to get the sight. "I flew across the hot top knowing that I was going to catch holy hell from the armorer," he recalled. All the personnel in the armory were permanent staff, and true to Sarno’s prediction, he was jumped on immediately when the staff learned why Sarno was there. "When I told the armorer that I needed a rear sight," said Sarno, "he asked, ‘What the hell did you do with the one we gave you?’ When I told him that I didn’t know, I got my ass reamed out from him as he was putting the rear sight in. He tossed the rifle back at me and I rushed out and joined my platoon. From that day on, every morning and every night I broke my sling apart, took the shiny brass claw, and used it as a screw driver to tighten that little bar that held my rear sight. I did that every day religiously, because there was no way I was going to lose my rear sight again."

Most recruits in Marine Corps boot camp had no love for their drill instructors, except perhaps that they would love to kill them. There were senior DI’s and junior DI’s, and they held the rank of private first class to staff sergeant. "Staff Sergeant Slater was our senior DI, but we hardly saw him," recalled Sarno. "I mostly saw him when the platoon was designated to perform for an officer, which wasn’t too frequent. He was pretty good. I can’t remember him ever abusing or cursing anybody out, but we towed the mark when he was drilling us. We wanted to look sharp for him. But Corporal Payson…. We could be the sharpest platoon, and he’d still treat us like scum. Our platoon’s 24/7 regime lay in the hands of the junior DI’s, and it was a shark tank for them to surface for notice of just how unmerciful they could be. Pfc. Gaunts was one of our junior DI’s. He looked like the movie actor Sidney Greenstreet, and when he chewed us out we didn’t take it to heart like we did with Payson."

Every drill instructor had certain criteria for training their recruits, but each DI had his own method of instruction, some more unconventional than others. There was corporal punishment, and Platoon 288 recruits received some punches to the face or an occasional backhander, especially from one in particular. "Payson was an SOB of a DI", Sarno recalled. "One day 288 went for dental exams," recalled Sarno. One boot had two teeth pulled and came out of the dentist’s office with gauze and puffy cheeks. When he entered the vestibule where the rest of the platoon was waiting, he dared to address Corporal Payson without permission. "Payson’s eyes narrowed," recalled Sarno, "and he let go with a backhander to that boot’s jaw that knocked him prone. ‘Who the fuck gave you permission to speak to the DI?’, Payson yelled."

Payson’s method of instruction included repeated attempts (most of which were successful) to publicly humiliate the young boots. Sarno remembered that there was a big tall recruit named Brown. "He was good," he said. "I can never remember him having a problem mastering whatever they were teaching us. He was quiet and confident. Payson goaded Brown every single morning like clockwork. This is how he started the morning: He got right in his face. And Payson was little. Brown was six foot, but Payson as a little shit. He’d go to Brown right off the bat. He got right up under his jaw and said, ‘Brown, is that your name?’ And he’d say, ‘yes sir.’ Payson would then say, ‘Brown, what’s the color of shit?’ ‘Brown, Sir.’ Payson would reply, ‘Then you’re a piece of shit, aren’t you Brown?’ He would reply, ‘Yes, Sir.’ Every morning Payson was at it. He would go to that one guy. And, of course, it got old to us. We knew what he was going to do and it didn’t have an affect on us—at least not in the beginning. We felt bad for Brown because he was doing everything that a boot should be doing. But Brown never reacted. He took the call-down. Payson was that mean."

But Payson’s occasional use of corporal punishment to help mold raw recruits into new Marines was nothing compared to the instruction methods of Parris Island’s infamous "Locker Box Jones." Sarno sympathized with the boots in that martinet of a DI’s platoon. "There was another platoon that camped with us," he recalled. "Their DI was famous. His name was Locker Box Jones. He was a mean son-of-a-bitch who punched out guys in his platoon. He even took rifles that weren’t properly set up. He’d take the rifle and throw it like a baseball bat right into the sand. He would just heave it like a javelin. He was known to demand that his recruits break out their heavy gauged wooden locker box and drill with them instead of a rifle. That’s how he got the name ‘Locker Box Jones’." A boot’s locker box was a small wooden trunk about 30"x18", and a little over a foot deep. It held personal items, toiletries, stationery booklet, Marines Guide Book, all items of clothing (including dungarees and dress shoes with shining gear), etc. It probably weighed about 35-40 pounds when full. "The day I saw Jones drill his boots with the locker boxes," Sarno said, "the recruits couldn’t hold them too long and they spilled their company street with the contents. Locker Box Jones was a tyrant—loud and abusive--and Hell on the island for years. Payson was only a pimple on Locker Box Jones’ ass. Our DI’s put the fear in us, there was no question about it, but Jones was a lot more miserable to his boots than my set of DI’s."

Sarno admitted that during his first few days and weeks in boot camp, he was frightened of the DI’s. However, his bewilderment at the verbal tirades eventually gave way to understanding why they were doing it. "I realized that they were trying to break us down mentally," he said. "I was going to resist them. I was going to yes them to death. Whatever you say. The more I yes’d them, sooner or later they had to move on to somebody else. I wasn’t going to say no."

After the initial shock of those first days in boot camp, recruits started to be conditioned to the verbal tirades from their drill instructors. "About three weeks into boot, the in-your-face ass-chewings rolled off of us like water on a duck in a rainstorm. Silently we were going to show Payson that he couldn’t break us down. Of course, that was Payson’s victory right then—boots who silently hated his guts, but wouldn’t give in to irrational conduct unless it was in order to kick his friggin’ head in, with pleasure." Payson even made mail call an ordeal for the boots. Sarno said that every two or three days the mail could come. Payson would stand between two platoons, call out the name of the man receiving the mail, and then throw the letter in the other direction. "Then if a guy got four letters," recalled Sarno, "instead of giving him the four, Payson would throw the letters one at a time on the floor and then make the guy run around the platoon and pick each one up off the floor. That’s just the way that Payson was."

Payson was hated by the recruits who were under his charge, but his demand for obedience got results. The majority of the boots in Platoon 288 survived his punches and his verbal tirades. Some recruits, however, did not fare so well at Parris Island, and Payson used this fact to his best advantage. He taunted those who thought they could survive boot camp by setting examples of those who had failed to survive it. One cold morning as Payson marched his troops to the grinder, he stopped the platoon. "There were two guys standing on the curb in light blue overcoats," recalled Sarno. Payson told his men to ‘right face.’ "We were facing these two guys, but we didn’t know who they were. Payson said, ‘See these two assholes? They couldn’t make it. They’re sending them home to their mommies and daddies in blue overcoats. Baby blue. They’re babies. They couldn’t make it. They want to go home.’ And Payson told the boots in Platoon 288, ‘Every one of you are going to get a blue coat.’ I can remember saying to myself, ‘F--- you, Payson. I’m making it, even if I have to go over you. You aren’t sending me home in a blue coat.’ And I’ll bet a lot of other guys were thinking the same thing. We were determined. But that’s the way it was in the Marine Corps. They wanted you to have that reaction—‘you aren’t driving me out. I’ll drive over you.’ They wanted that, because it was all leading up to combat training. You’re going to get that enemy. Even if you’re surrounded, you’re going to get that enemy again and again until you’re wiped out. You’re going to do your duty. All these little things were geared for combat. We didn’t know it at the time, but our DI’s did. I’ll always remember those two kids in the blue coats." As for the boys in blue, they just stood there like statues as Payson ridiculed them. Apparently they were afraid to move, for fear they would be thrown into the brig. "They didn’t move an inch," recalled Sarno. "We sort of looked down on them. We’re going to make it. You guys aren’t good enough. That was our reaction. Early Marine attitude. I’m better than you." The boys in the blue coats were left behind that day as Payson marched his determined boots onward to the grinder.

The grinder that the new recruits saw as they first entered Parris Island became a very familiar place to every Marine and Marine recruit on the island. "There would be massive platoons out there maneuvering and doing the same basic close order drill," recalled Sarno. "Close order drill was not just marching or learning to march. It was done with foresight. It taught you instant discipline to react to a command. Right flank, left flank." It was a monotonous routine, and many recruits, including Chris Sarno, wondered, "Why do this? It’s boring." In hindsight, Sarno finally came to understand the answer to his own question. "The way the Marine Corps looked at it," he explained, "it taught you inner discipline to obey a command instantly without question. And we didn’t question—we just did it."

Each day began for Platoon 288 at 5 o’clock in the morning. Sarno was awakened each morning by "heels, heels, heels"—the sound of another platoon marching by the hut at 4:30 a.m. to be first at chow. The stomping of their boots woke up the occupants of other huts on the street, too. A normal day didn’t start with push ups and jumping jacks and other physical exercise like one sees in the movies. "We didn’t do a lot of physical training," recalled Sarno. We never did those calisthenics that you see them do now. The Marines that you see today are hard body guys right out of boot camp. Maybe it was on account of the Korean War that they skipped that when I was in boot camp, but we had no hard physical training. We did calisthenics in the morning, but they were a snap. They were only five minutes, but we were hardened just the same. We had good muscle form."

Besides the short daily physical training sessions, there was classroom instruction on subjects such as the history and traditions of the Marine Corps and personal hygiene, field days of cleaning, and close order drills. During the days and weeks that followed their arrival at Parris Island, the new boots underwent the gamut in training from before sunup to after sundown. There were occasional "unusual" tests, too. One cold winter’s night before their boot camp days were over, the platoon put on Navy blue, all wool bathing suits that were (as Sarno called them) "itchy as a bastard." The boots then double-timed to the swimming pool. "The DI’s were laughing," recalled Sarno. "They said, ‘All you clowns that can’t swim will drown tonight.’ I laughed to myself because I already knew how to swim. It was a big, heated pool, and the swim instructors had each one of us swim the length of the pool and back—50 yards. I dove in and did my swim up and back with no problem. When I got out, I observed the poor boots who couldn’t swim. Some refused to get in, but the instructors pushed them in at the deepest end, which was 15 feet deep. They sank fast, screaming like dying men. The instructors had long bamboo poles that they put into the water for the sinking boots to grab on to in order to surface. They remained in the water as the instructors made them be buoyant at best. I remember that one boot fought off getting in the water. They dragged his ass up to the highest platform over the deep end and threw him down into the water. He hit bottom and remained there. The instructors finally all dove in to rescue him." Those who knew how to swim were marched back to the barracks. Sarno said that much later the non-swimmers were dragged into the squad bay where they were "berated like shit-coolies." They went back to the pool the next night for swim classes. "We felt for them, but we didn’t dare say shit," Sarno said. There was deep comradeship among the boots, but those who showed deficiencies often got the cold shoulder from their fellow recruits. There was no room for weakness in Marine Corps boot camp.

Once the boots mastered close order drill and the manual of arms, their attention was turned to the rifle range. A month had passed since they had arrived at the front gate to Parris Island. There were only four more weeks of boot camp training left. The normal peacetime training time was 12 weeks, but with a war raging in Korea and replacements desperately needed there, the recruits were put through an accelerated training course. This part of the training—teaching boots to shoot with precision—was all important to the Marine Corps, which mandates "every man a rifleman." After boot camp was over, Chris Sarno was assigned to tanks, but nevertheless, he was trained to be a rifleman as every Marine was and still is trained. "All Marines are capable of being put into a rifle platoon and functioning as a rifleman, regardless of what you learned as your specialty," he said. "All the Marines have that in them and take great pride in knowing that, yeah, I’m basically a Marine rifleman and I can function as a grunt even though I’m trained as an artilleryman or a tanker or an amphibious guy. We’re all proud to be infantrymen. There’s no problem mentally saying, ‘what am I doing here?’. I guarantee that if you interview any Army guy and ask him if he’s been trained away from the infantry in the Army and suddenly he’s going to have a rifle in his hands, he will piss and moan and complain, ‘Hey, I’m not trained for this. I shouldn’t be here.’ And he will belabor that point. ‘Get me out of here. I didn’t join the Army to fight.’ But that is so totally foreign to the Marine training—of the mindset. A Marine won’t say that. They’ll accept that rifle and say, ‘Okay. What’s my duty within the squad?’ That’s the difference in Army and Marine training."

When it was time to go to the rifle range, the lives of the men in Platoon 288 altered. They were moved out of their metal Quonset huts and into spacious wooden barracks closer to the rifle range. Rather than being fractured apart in four or five huts, the entire platoon was together under one roof. There was better lighting and uniform racks on which to sleep. In the center of the squad bay was a long rifle rack. Meals were served at the boot mess hall, and Sarno said the chow was good.

Each morning the boots underwent thirty minutes of physical training, doing exercise with the M-1 rifle to build up the upper body. There would be no live rounds used in their first days of rifle range training, but it was deadly serious business for the recruits just the same. What they absorbed from their instructors would likely help save their lives should they go to combat in Korea.

At the rifle range, the boots were ordered to go up to staked places in the sand. There, they lined up in a skirmish line and for one week learned how to "snap in". Their concentration was on one thing only: They practiced sight alignment in offhand (standing), sitting, kneeling, and prone positions. On a stake in front of the boots were two other pieces of wood with the silhouette of a target. Initially, the boots were taught how to get the proper sight picture only. "They taught us how to get a bull’s eye," recalled Sarno. "We had to line up at 6 o’clock on the silhouette, have the circle part of the end of the barrel with the perpendicular stud coming up, hold our breath, let a little out, and squeeze the trigger. We did that religiously for seven days."

After practicing over and over again on how to focus on their target, the boots moved to the firing line and butts area of the rifle range. (The butts were the target pulling area.) For many of the boots, this was the first time they would ever fire a rifle. "The targets were huge," recalled Sarno, "and I thought to myself, ‘How in the hell can you miss these?’ But this was the first time I ever fired a weapon in my life." What seemed simple in theory proved to be harder in practice.

Supervising the rifle range training were firing instructors whose only job in the Marine Corps was to teach boots how to qualify. "He didn’t want it on his record that he had a boot that didn’t qualify," said Sarno. Each instructor was assigned four or five recruits, and he worked with them day after day to make sure that those in his charge qualified and his record as an instructor was proficient. "I remember my instructor’s name," Sarno said. "His name was Holmes and he was okay. He was nothing like a DI. There was a big difference between rifle range personnel and DIs. Permanent personnel treated us relatively good. The DI’s had nothing to do with us during rifle range training. They brought us down in the morning that first week, and then they left us. We were then in the hands of the range firing people, which was nice. For once we weren’t under constant belittlement. But they did that so that we would be calm enough to qualify. The second week was the same thing. We fired live practice rounds. No DIs were bothering us during the day. But at night the DI’s said that everybody better qualify. That was the last thought on our mind as we went out the final day on the rifle range: to qualify." Rather than risk the wrath of their DI’s, the boots paid close attention to their firing instructors.

Supervising the rifle range training were firing instructors whose only job in the Marine Corps was to teach boots how to qualify. "He didn’t want it on his record that he had a boot that didn’t qualify," said Sarno. Each instructor was assigned four or five recruits, and he worked with them day after day to make sure that those in his charge qualified and his record as an instructor was proficient. "I remember my instructor’s name," Sarno said. "His name was Holmes and he was okay. He was nothing like a DI. There was a big difference between rifle range personnel and DIs. Permanent personnel treated us relatively good. The DI’s had nothing to do with us during rifle range training. They brought us down in the morning that first week, and then they left us. We were then in the hands of the range firing people, which was nice. For once we weren’t under constant belittlement. But they did that so that we would be calm enough to qualify. The second week was the same thing. We fired live practice rounds. No DIs were bothering us during the day. But at night the DI’s said that everybody better qualify. That was the last thought on our mind as we went out the final day on the rifle range: to qualify." Rather than risk the wrath of their DI’s, the boots paid close attention to their firing instructors.

Learning to fire was not a free for all for the boots. Each was given full clips of eight rounds, and they were closely supervised by range officers who were responsible for the safety of their inexperienced charges. "You could only function on the command of the range officer," said Sarno. "He had a bull horn and would shout, ‘All ready on the right. All ready on the left.’ We were allowed to take our time—we didn’t have to rush the eight rounds off." But they were expected to be precise in their shooting because each boot had to "qualify" (get a certain score) in order to graduate from Marine Corps boot camp. The man working the butts area would check the target to see where the eight rounds hit the target. "At certain areas you got two points, three points, four points, and five for the bull," recalled Sarno. "I don’t think I got a bull the first time, but I wasn’t all over the target like some of the other guys."

For an entire week, the recruits practiced firing over and over again every day. On Friday of the second week at the rifle range, the men would have to fire 50 rounds for record. "Your score went into your Service Record book," explained Sarno. "Any score under 190 and you did not qualify. I fired 196, which was Marksman."

Not every boot in Platoon 288 qualified, and woe to those who didn’t. "We had five boots who didn’t fire 190 or higher," recalled Sarno. "As the DI’s gathered us up after morning session firing for record…our two weeks were up on the rifle range…right away the DI’s wanted to know, ‘who the f—k didn’t qualify?’ He berated them something fierce, and made them march behind the rear platoon. The DI called them a ‘platoon of assholes’—‘shitbirds.’ When we went to noon chow that day, those who hadn’t qualified on the rifle range had their skivvies tied on as bibs, and one could see the white skivvies scattered here and there in the huge mess hall. We even ragged them in the barrack to a degree, but within a week it was a non-issue." Graduation was nearing. Boots who didn’t qualify on the rifle range were allowed to graduate with the rest of their boot camp buddies, but the fact that they didn’t qualify with the rifle was noted in their service record for viewing by the commanding officer at their assigned post-boot camp duty station.

Besides snapping in and firing on the rifle range, the recruits learned another important skill required of all Marine riflemen. They were taught how to break their M-1’s down to clean its intricate parts, and then how to re-assemble the weapon rapidly. "While learning and doing the manual of arms before," recalled Sarno, "We would field strip the M-1 just for practice. But out on the rifle range and at the cleaning racks, we loved the M-1 like a girl friend. It was our best pal in combat that M-1. We treasured it, and I never let mine hit the deck in all the four years that I handled it. I loved the M-1 and the unique noises that it gave out while we were in drill with it. The US Marine Silent Drill team uses M-1’s as they make a unique sound when snapped hard."

Sarno and the other boots may have qualified as riflemen, but ranking Marines on the base made sure that it didn’t swell their heads. During rifle range training, recruits spent the third week doing menial tasks in mess duty for all the rifle range coaches and other permanent personnel there. Boots on mess duty that week were awakened by the fire watch at 3 a.m. Once in the mess kitchen, they were at the beck and call of their new bosses—the cooks. "The meanest guys in the Marine Corps were its cooks," Sarno noted. "They never smiled, and we were just faceless bodies as they ruled their roost. You were told what to do and were expected to do it without further question. Those cooks were martinets." Sarno said that he didn’t mind the cooks because being assigned mess duty at the rifle range was far better than pulling mess duty at Main Side. "It was much easier and closer-knit doing mess on rifle range week than serving 1,000 boots at Main Side. After the morning chow was over and all nine tables were spit shine clean, we would line up the salt, pepper, tomato bottle, salad oil jars, silverware placings, two plates, one cup and one glass, and then three boots would stretch a long string across four tables. Each of the above items had to be in precise alignment. It was a perfect spectacle to walk in and savor a dining hall in order. Mess duty taught me for the rest of my life how important cleanliness is in food preparation." The rifle range mess hall had an ocean view, and Sarno said that, with the sun streaming through its large windows and hitting a gleaming deck, the pristine setting seemed somehow romantic.

The area called Elliott’s Beach was not nearly as "romantic", however. Due east and near the rifle range, but not in sight of it, Elliott’s Beach was a lush area with lots of 10-15 foot high scrub palms and sea grass. Not long after they had completed their instruction and proficiency test on the rifle range, the boots were sent on a forced march to Elliott’s Beach. They wore a 60-pound combat pack complete with M-1 rifle and all web gear and attachments. "We had two weeks left on the island," said Sarno, "and we were salty bastards. We moved out in two columns and the DI’s blew whistles to hit the deck (in a salt marsh) to simulate being under air attack. We were eating this up as it was gung-ho. The scenery was all salt marsh tributaries like an estuary to the sea. When we finally arrived at the staging area to the beach, we were all muddy and wet. We had a good noon chow and then half the platoon went to assault the fox hole position while my half went to the familiarization range and fired .22 caliber rifles. We also watched a 2.5 World War II bazooka team fire a couple of rounds, and we fired the .45 caliber pistol at wooden targets about 25 yards way. We thought, ‘this is so easy at that close range.’ I fired about 25 rounds, but I never hit the target once. Most of us did the same. The pistol coach said he was not surprised. We learned how inaccurate the pistol could be without constant practice with it. If you do hit your enemy with it, you’ll blow his head off."

Later, Sarno’s section assaulted foxholes by fire team coordination. There was no real guidance, Sarno recalled, and the men didn’t know if they had done the assault correctly or incorrectly. "There was a lot of yelling in the assault, that’s all," he said. When the assault training exercise was over, the men marched two miles back in a tactical march that still included hitting the deck when the DI’s blew their whistles.

"The tide was coming in on the salt flats," recalled Sarno. "Guys fell in deeper water this time. We got back drenched, muddy, and tired, but we ate it up just the same." In the months to come, many of these new Marines would experience much rougher training at Camp Pendleton. But for now, they concentrated on their last days on Parris Island. They spent one morning in a gas chamber, learning the basics of dealing with chemical weapons. They were required to stay in the chamber for several minutes until they were ordered out and into fresh air. They dashed out stumbling and coughing, eyes runny from the sting of the gas—but one step closer to graduation for having gone through the experience.

With the promise of that graduation just a couple of weeks away, the boots who had made it through boot camp training thus far were fitted for dress greens. Civilian tailors fitted them for their greens, as well as for khaki shirts and field scarves (ties). "I loved looking at the Marine emblem on my dungaree blouse and gung-ho cap," Sarno admitted. "As mentally grueling as it was, I loved being a Marine. It was the final ending of my boyhood, and adventure here I come!"

After rifle range training, the last two weeks of boot camp were relatively easy. "There were classes on military subjects pertinent to the USMC mindset," recalled Sarno, "and the DI’s didn’t really scare us anymore, no matter how they yelled in our faces. We also took one more written test about boot camp subjects. The DI railed at our results. He screamed at us that as a platoon we had failed miserably on the test. He yelled, ‘One of you shitheads couldn’t even spell your name correctly. You are undoubtedly the dumbest bastards I’ve ever trained.’ But, we were the saltiest SOBs he had ever seen, too."

Every new Marine wanted to be "salty." This term often crops up in the Marine vocabulary, and it has different meaning depending on how it is being used in conversation. A salty Marine has the persona of what it takes to be a sharp-looking Marine. He is a seasoned Marine—somebody you can go to and depend on if you have a problem. Salty uniforms have a "not new" look to them. As each day of his boot training came to an end, Chris Sarno washed his cover (cap) every night until it was almost white rather than the herring bone green it was when he arrived at boot camp. Just days before graduation, his platoon was marching to noon chow. Drill instructor Gaunts noticed Sarno’s cover and said, "You salty little bastard." Just to remind him that he was still a boot, albeit a "salty" one, Gaunts pulled Sarno’s visor down over his eyes. "He said, ‘right face, forward march,’ recalled Sarno. "Now turn and march. Keep your goddamned head down, Sarno. Stop looking. Keep that head up erect. You’re at attention.’ And I was staggering all over the place. The guys were pushing me because I was screwing them up. Finally we got to the chow hall and Gaunts told me to restore my cover."

Boots worked up an appetite during their arduous training, so chow time was always welcome. They were marched to chow hall, then had to wait a half hour before they went in. "It was hurry up and wait," said Sarno. But the food was good and worth the wait. "We had potatoes morning, noon and night," he recalled. Occasionally there was steak and maybe pork chops. Meat loaf, baked liver and chicken legs were common fare. These were served along with peas, carrots, spinach and other vegetables. "We also got one slice of ice cream all wrapped up in white paper," Sarno recalled. "They made their own ice cream. It was sort of a cheap, milky-tasting ice cream, but we dove into it. We had milk and cereal in the morning." Hovering nearby were the drill instructors, making sure that their charges ate. There were no seconds in boot camp, so the boots ate the food that was piled onto their plates like they were starving. The Marine Corps had complete control over who ate what, too. "The fat guys—the overweight guys—had a special table where all they ate was lettuce and tomatoes and carrots," recalled Sarno. "It was called the rabbit table." Everyone at that table was on a strict diet of low calorie foods to help them lose weight. Sarno, a mere 129 pounds, was told by one of his junior DI’s that the Marine Corps intended to put twenty pounds on him. "Sure enough," Sarno said, "when I got out of boot camp, I weighed 150 pounds. And like I said, you only got one serving at breakfast, dinner, and supper."

Boots worked up an appetite during their arduous training, so chow time was always welcome. They were marched to chow hall, then had to wait a half hour before they went in. "It was hurry up and wait," said Sarno. But the food was good and worth the wait. "We had potatoes morning, noon and night," he recalled. Occasionally there was steak and maybe pork chops. Meat loaf, baked liver and chicken legs were common fare. These were served along with peas, carrots, spinach and other vegetables. "We also got one slice of ice cream all wrapped up in white paper," Sarno recalled. "They made their own ice cream. It was sort of a cheap, milky-tasting ice cream, but we dove into it. We had milk and cereal in the morning." Hovering nearby were the drill instructors, making sure that their charges ate. There were no seconds in boot camp, so the boots ate the food that was piled onto their plates like they were starving. The Marine Corps had complete control over who ate what, too. "The fat guys—the overweight guys—had a special table where all they ate was lettuce and tomatoes and carrots," recalled Sarno. "It was called the rabbit table." Everyone at that table was on a strict diet of low calorie foods to help them lose weight. Sarno, a mere 129 pounds, was told by one of his junior DI’s that the Marine Corps intended to put twenty pounds on him. "Sure enough," Sarno said, "when I got out of boot camp, I weighed 150 pounds. And like I said, you only got one serving at breakfast, dinner, and supper."

As a result of his boot camp training, Chris Sarno had changed in ways other than physical appearance, too. "I always had a deep resentment for someone telling me what to do," he admitted. In boot camp, he had to sleep, eat, and speak only on command. The drill instructors had constantly told him what to do. "But I didn’t fight it," Sarno said. "I learned how to be disciplined, and I was better off for it."

There was only one black recruit in Platoon 288. Like the other boots on Parris Island, he did everything he was told to do, and he did it well. He was a quiet man who caused no problems. As a result, there was no racial tension because of his presence in the platoon. Cooper was his name. In spite of the fact that he had proven himself worthy to be called a United States Marine, when everyone else got orders that they were going to Pendleton, Cooper got orders to Baltimore. Sarno recalled, "I said to the DI, Baltimore? There are no Marines in Baltimore.’ The DI replied, ‘You’re right. He’s going to be a steward in an officer’s mess. That’s the way we do it." In 1951, there were no blacks in combat outfits. For Sarno, this didn’t seem like anything unreasonable. He had grown up in an all-white neighborhood where different races did not mingle. "They were black and we were white, so we didn’t socialize with them," he explained. When Sarno entered the Marine Corps, the segregation that still existed didn’t seem out of the ordinary to him. "Even going through training and replacement command in California," he recalled, "there were all whites. I didn’t think anything of it—why Pendleton was nearly all white. That was just the Navy. They weren’t listening to President Truman in 1948 when he desegregated the Armed Forces. Sure he did it publicly and he signed a law, but it wasn’t implemented. The Navy was very hesitant to put any black in a combat billet, whether in the Navy or Marine Corps." Growing up in a white community, Sarno said blacks weren’t in his life. "They were the comical guys," he explained. "They were seen, but not taken seriously."

Whether black or white, the boots on Parris Island knew that their brutal days on that "asylum on the island" were almost over as graduation day arrived. The men in the three graduating platoons put on their greens and passed in review before every senior and junior officer in battalion formation. The drill instructors were tense, demanding that their graduating recruits not "screw up on battalion parade." Even the DI’s were answerable to higher authority in the Marine Corps. If their platoons fouled up on this very important day, the drill instructor’s proficiency would be lowered because their performance as DI’s was measurable by the performance of the boots under their supervision. "They were really sweating that we were going to foul up," said Sarno. "But we didn’t."

After the battalion parade, the graduating boots felt that they were real Marines. "All of us thought we were," said Sarno. "We had done everything they wanted of us and we passed. In the Marine Corps, you either pass or fail. We had passed and we were all proud of ourselves." That night, the men in Platoon 288 overheard another platoon’s drill instructor still belittling his boots. "We could hear him," recalled Sarno. "He was ranting and raving, ‘You’re going to Korea. You’re all going to be killed. You’re cannon fodder. You think you’re Marines? You’re not Marines."

The next day the new Marines went their separate ways. "We got our sea bags and we were going home for ten days," recalled Sarno. "We were happy. Two DI’s came down and they were still cursing us. We got on the bus and they were still cursing us. As the bus slowly pulled away, somebody said, ‘Let’s tell those assholes.’ We rolled the window down and yelled, ‘F—k you.’ Out of sight, out of mind," Sarno said, "after we went over that damn bridge, I forgot about my DI. I didn’t like him, but he was no longer in my life."

A Greyhound bus took Chris Sarno further and further away from Parris Island and the hated DI’s, and closer and closer to his home and his beloved family near Boston. While waiting to change buses in the New York City terminal, Sarno was able to put some of his newfound confidence and skills-under-pressure to work. An elderly man was having an epileptic seizure, trashing around on the floor of the terminal and frothing at the mouth. Sarno had seen this same type of medical condition with one of the boots on Parris Island. "Not one of the bystanders were doing anything to assist this poor fellow," recalled Sarno. "I took immediate action by loosening his tie. Next, I asked for a wooden pencil and managed to insert it under his tongue to prevent him from swallowing his tongue. The New York police arrived and took him away. When one of the officers asked who had helped the man with the seizure, I told him that I had. He publicly gave his praise and said, ‘Thank God a Marine was on the scene to help save this man’s life.’ It was a nice feeling being of assistance as I moved on to board the bus to Boston." Just like the day he had arrived on Parris Island, the music on the bus included the Perry Como hit, "If." Sarno said, "To this day I associate my entrance into the USMC and those two bus trips in early 1951 with Perry’s hit tune." The trip from Parris Island to Boston took almost 20 hours. He arrived at Park Square on a cold March morning, and took the subway/bus system to his boyhood home.

At 5:30 in the morning, Chris Sarno tapped on the door of his parents’ home. His father opened the door to a young Marine wearing a sharp green uniform. "I remember him opening the door," reminisced Sarno. "I put my arms around him and he embraced me. I kissed him on the cheek, and I broke up crying." For Chris, he was on a new plateau in life. He had accomplished something that he never dreamed he could. "Nobody in my family had ever experienced what I had just been through," he said. "But when I cried, my father didn’t say anything. He just patted me as if he understood. Yet he had never been in the Armed Forces." This tearful moment was short-lived, and just between the senior and junior Chris Sarnos. When his mother realized who was at the door, she came rushing into her son’s arms. "She had tears of joy and was so happy I arrived," he recalled. "There was no big party or hullabaloo—just an intimate demonstration of family love and affection." The fact that his mother was happy because her son was finally home made the Marine happy, too. "My mother was very uptight about me being in the Marine Corps," Chris explained. His mother’s hope was that her young son/Marine would get stationed at the Boston Navy Yard. "But I knew better," Sarno said. "Korea was for me. But even when I was in combat, I never wrote home about it. My mother would have worried too much. She was the only family member to write me and send items to me on a dependable timetable."

His tour of duty with the Fleet Marine Force would still be months down the road, however. For now, he enjoyed his time on leave by taking in all the movies in the big Boston theaters, and by eating at the best restaurants in Boston. "My favorite restaurant was Peroni’s, where the fried clams were an Epicurean delight," he said. "That place in downtown Boston was always packed. I would sit up in the raised part of the flooring up back, always ordering the clams and a small bottle of champagne cocktail which would fill the glass twice." It was wartime, and, just like he had admired uniformed World War II veterans during the previous war, Chris Sarno now received his fair share of looks of admiration as a uniformed Marine. "I was one sharp-looking Marine decked out in dress greens," he said, "and the times I was in public, you bet I was in uniform."

One weekend, Chris was joined at a restaurant by his uniformed brother, Bud. "My mother knew in advance the day I was coming home on leave, so she moved fast," explained Sarno. "She was politically connected and had someone clear it for my brother Bud to get a weekend liberty while still undergoing his boot training in the US Navy at New Port, Rhode Island. Sure enough, the two of us shared a weekend in the Boston hot spots." When Chris joined the Marine Corps, Bud was attending the University of Massachusetts. Having discovered that his older brother Chris had decided to give service to his country during wartime, Bud wanted to join the Marines, too. But he was only 17 years old, and as such he needed a parent’s consent—which his mother flatly refused to give. "My mother had a brother on Guadalcanal in World War II," said Chris. "He told her just how tough the Marines had it on that friggin’ island, with tremendous KIAs and WIAs. My mother saw nothing but death as a Marine. But she slowly relented in her refusal to allow Bud to enlist, telling him that she would sign for him if he would join the Navy rather than the Marines—which he did." For Sarno, about to depart for further Marine Corps training in California, it was great to spend a couple of days with his brother. "During our high school years," he said, "We were almost like twins—always together playing baseball, basketball, outdoor ice hockey, and sandlot football."

Now, however, thousands of miles would soon separate the Sarno brothers. Chris climbed aboard a four-engine TWA for his first plane ride, which took him to California, and Bud went back to Newport, Rhode Island, to finish Navy boot camp. Before completing boot camp training, Bud scored very high on his military test and was asked if he wanted to go to Officers Candidate School. He declined, and instead went on to attend "A" school at Jacksonville, Florida. He had his pick of man o’ war ships on which to serve, and chose the USS Antietam, which was berthed at Norfolk, Virginia following its return from duty in Korean waters. Bud Sarno spent three years in the Navy in the Atlantic Naval Command, with his home port being the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The Antietam also went to England for a few months during Bud’s tour of duty on it. While Bud finished boot camp and got further schooling in the Navy, his brother Chris would be getting acquainted with the west coast and undergoing combat training in anticipation of a tour of duty in Korea.