"Being a Christian, I don't intend to be bitter about Korea, but I don't intend to be silent any longer, either. My question is why were we silent for all these 50 years?"

- James W. Scarlett

The following memoir is the result of sets of questions and answers about the Korean War that were exchanged between James Scarlett of Tennessee and Lynnita Brown of Illinois by U.S. mail. James Scarlett does not own a computer. Lynnita sent the questions to Jim, and he responded to each set by sending answers written out in long hand. His answers were then combined by Lynnita into the narrative you see below.

I was born at Gentry, Tennessee, in Putnam County on 28 November 1931. Gentry is near Baxter, and about ten miles from Cookeville. My parents, Harley T. and Winne C. Brown Scarlett, named me James Wilson Scarlett. I was born in a log cabin to a share-cropping family - very poor people. We lived on and worked somebody else's farm. I was raised up very hard. Dad was rough on all of us kids, but I will share how this paid off for me in Korea later.

My dad was a farmer, and worked for the Work Projects Administration (WPA) during the Depression. He learned how to cut hair and became a barber. He also did sheet metal cutting, learned how to be a carpenter, and also did road construction work, but he held most to farming. My dad was a hard man and a big man. He stood about 6'1" or so, and weighed about 210 pounds. He could take a 16 hand mule with the left hand and whip him in a circle with the right hand. He was very strong. He was a good man, but when he got to drinking, he could get mean and sometimes mistreat my mother. That didn't go over too good with me. Mother was strictly a homemaker. I think that before she married my dad, she worked as a telephone switchboard operator for a while.

Seven children were born to my mother and dad. I am the oldest. My siblings Earl T., Joe Mac, Emma Sue, and Anna Ruth are now deceased. My brother Harry D. Scarlett and sister Jane Evelyn are still living. We went to grade schools in Putnam County, Tennessee. I attended Cedar Hill Elementary School, Chestnut Mound Elementary School in Smith County, Tennessee, and Baxter, Tennessee Elementary School. I attended my first year of high school at Baxter Seminary High School, but entered the military before I finished high school.

As a youth, I spent about two years and maybe more in the Boy Scouts. I also played baseball. I was second pitcher on the baseball team, pitching over-handed, not side arm. I remember that there was a fellow on the team named Preston Presley. He was always blowing hot air, and one day I hit him upside the head. I thought I had killed him. They laid him in the shade and poured water on him. That kind of unnerved me.

I worked after school in the evenings. While in grade school, I cut grass and painted some. There was a lady named Mrs. Oliver in the little town of Baxter where we lived, and she and her husband owned a small hotel. I made beds, mopped floors, cleaned windows, raked the lawn, cut grass, weeded her garden, and cut wood--whatever she wanted done. My after school work in high school followed about the same pattern.

World War II was going on while I was in school. My dad's youngest brother, Charles Scarlett, was in the war, and he served in the Army Air Corps. I think he was a gunner on one of the planes. He served in the Pacific, but when he came home he didn't talk much about it. I cannot speak for the other students in the schools I attended during World War II, but I remember collecting scrap iron to sell it to support the war. I tried to keep up with what was going on in the war by asking my paternal grandfather questions about it.

Back in the 1940s and 1950s, when a young man reached his 18th birthday he had to register for the draft. Tennessee at that time had draft boards in many of its towns. I registered at Cookeville, Tennessee, at Local Board #75. There are no local boards today because there is no draft. After registering at the local draft board, I was not called to be examined until I was almost 21 years old. In the meantime, I joined a country music band out of Ohio named the Conger and Santo Players in the early spring of 1948. The band came to Baxter to play circuits in Tennessee. They set up headquarters at the old hotel, which was owned by my dear friend Mrs. Oliver and her husband.

I had purchased my first guitar from a young man in Baxter. It was well-worn, but it still had a good sound. This young man's dad played fiddle, and he and his son played rhythm. They played cake walks, pie suppers, and different kinds of local events, so I finished it wearing it out. I ordered a small guitar by mail order catalog. It was a "Bob West" guitar--a small Gene Autry type--with a western cowboy scene on the top. I also bought a course booklet to teach myself how to play it.

Since I worked for Mrs. Oliver after school in the evenings, she introduced me to the Conger & Santo Players. They asked me quite a few questions about my life and family and playing the guitar. I tried out with them and they wanted me to go with them to the Ozark Mountains of Missouri. I was not sure about it at first, so I talked to my mother about it. She was not sold on the idea. My dad and I did not get along as good as we should have, so I told Mother that I was going. I left with some strained feelings between me and my dad. When I left Baxter, I stayed gone for about four years, but I did write to my parents. Sometimes I became homesick while on the road those four years, but dating young women and playing music for the most part kept my mind at ease. Forgiving is a great cleaning to the soul. My mother accepted my leaving with the show troupe. We had that understanding. But my dad did not say either way. I cannot answer for him.

The Conger & Santo Players played waltzes, polkas, western swing, and country. (We had pop music even at that time.) I was the number one lead singer. I sang country songs such as, "Hey Good Looking" by Hank Williams, "Have I Told You Lately That I Love You," "Too Old to Cut the Mustard Anymore," "Tumbling Tumble Weeds" by the Sons of the Pioneers, "I'll Sail My Ship Alone" by Moon Mullican, and many more. They were all accepted at that time. One of the band members played accordion. His name was Karl Eggert and he was from Germany. He was some musician. There is no instrument in the world for rhythm like an accordion -- bar none. The fiddle or violin player was also an accomplished musician. He was Santo--a Jew from Hungary. Conger was the clown and played rhythm guitar.

We also put on "bit skits." They were short and I played the female parts. I became proficient at playing them. Some folks would want to meet the lady that was in the act, so Mr. Santo would say she had to leave shortly after the act. That is how we got around them not knowing it was me.

My pay scale was from $15.00 to $25.00 a week, along with my board. We were not union players; in fact, I did not know what a union was. I didn't suspect anything. We operated under a big top tent. We put up in each town and spent from six to ten days in the town, depending on the attendance. It was hard work putting up and taking down the tent. Conger and Santo promised me a career in Hollywood, but it didn't turn out that way. I had to go to Korea. When I came back to the States, they wanted me to join up with them again. But by that time, college was more important to me than getting back to the band. I did not play professionally with another band after I came back to Korea, although I could have if I had chosen to do so.

When the war broke out in Korea, I did not know anything about Korea. In fact, I did not know where the place was at, or that it was 11,000 miles away from home. What little I did get to know was from newspaper headlines and news on an old Montgomery Ward battery-powered radio. Television was coming in at that time, and if I could be somewhere that somebody owned one, I heard a few headlines. I was just a dumb old country boy. (I still wonder if I know much today.) From the time the war broke out until I was drafted, I paid very little attention to what was going on over there. My music kept me busy. Some people talked about the war, but I really did not know what they were talking about. I did not know what Communism was about. But I dedicated myself to know and find out when I came back from the muddle mess. I think I know a few things today that I didn't know then.

At the time war broke out, I didn't have an opinion about the war in Korea because I didn't know anything about it. I had no idea if troops would be sent to Korea or not. I had no idea if it would be settled soon or if it would go into a prolonged period as we know today that it did. In fact, I really didn't know much about World War II, other than a few things my grandfather (my dad's dad) had told me about being across a big wide ocean and thousands of miles away. What would a dumb country boy like me know about World War I and World War II, and Korea. That is where I stood.

My mail did not catch up with me so easily at that time because we played many towns in Missouri. Then, we left Missouri and went to Mississippi where we played circuits there. My examination notice caught up with me at Walker, Louisiana. I did not have time to go back to Tennessee and be examined, so that put me on the spot. Walker did not have a local draft board, but Denham Springs, Louisiana, did. My boss, Mr. Santo, said, "Let's try and get a transfer from Cookeville to Denham." On a Saturday morning, we left Walker for Denham Springs, hoping we would find someone in the office that morning. We did. She was a lady with a small child, and she was in a bad mood. I don't know if it was because of the child or because she had family problems. She did not want to take my case, but my boss spoke up and explained that I couldn't make it back to Tennessee on the date set for my examination. She finally agreed to have it transferred to Louisiana. She was mad. I won't ever forget what she said to me as I got ready to leave. She said, "If you are not here on Monday morning to take the bus to New Orleans for your examination, it will be your little red wagon." That shook me. On that Monday morning, I was the first name called to board the bus.

When I got my draft notice, I did not want to go. I had gone home for a few vacation days and wanted to go back on the road in show business--to the music I loved. The draft notice shifted every cog in all of my plans, but the Army or Armed Services have a way of doing that. Nevertheless, I grew to love the military down through the years that followed. I am proud for what I did for my country now that I understand some of the formats of the reason. When that general from South Korea hung that 50-year medallion around my neck at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, I knew then that I had served my country well.

The trip to New Orleans was an all-day affair. I passed the examination and they informed me that they would let me know when to report for basic training. We left Louisiana for the Ozark Mountains again to play another circuit. The next Christmas, the band members wanted to go home for the holiday. Some went to Ohio, and some went to New York. They wanted me to go to Ohio with them, but I said no. I wanted to see my folks in Tennessee. When we left Missouri, I left the other members of the band in Memphis, taking a Trailways bus via Nashville to get home to Baxter. I had been away from home almost four years. I had a two weeks visit at home, and then a notice came for me to report to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, for basic training. My folks had little to say about my leaving for basic training. After all, I had been away from home for almost four years. That may have helped some, but I am sure they had deep thoughts about it.

The year was 1952. I traveled to basic training by another Trailways bus, going from Baxter via Nashville to Fort Jackson. No one that I knew traveled with me to basic training. It was an uneventful trip, stopping at towns along the way for rest and refreshment.

When I arrived at Columbia, a few miles from Ft. Jackson, South Carolina, I boarded a military bus from the base that took us to the reception center at Fort Jackson. It was mid-fall of 1952. From the reception center, we were assigned to a training company. Sometimes new recruits stayed several weeks in a reception center. There could be many work details at the center: police call, picking up paper and cigarette butts; KP, kitchen police; barracks guard; CQ runner, in charge of quarters. NCOs were in charge, with a trainee runner. There was the filling out of many forms, medical records, Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) tests to see what field of training we would fit into best such as medics, cooks, MPs, infantry, administration, or special services. Later in my military career, I grew to dislike a military reception center deeply.

That first evening, I was in line to draw linen for my bunk. It was raining and I was mad because I had been drafted. While standing in line, Faron Young, the Grand Ole Opry star who had finished basic training and was assigned to special services, came down the line in the rain asking for musicians to join his band. His famous hit song at that time was, "Going Steady." In my anger, I kept my mouth shut and did not step out and let him know that I had just come off the road playing with the Conger and Santo Players as lead vocalist and guitar player for about four years. I have often wondered what my military career would have been like if I had taken him up on the challenge. He has been dead now for quite some time.

I was assigned to Love (L) Company on Tank Hill at Fort Jackson. Tank Hill was, and is, on a hill. I do not know what the degree of incline is. A big water tank was at the top of the hill with big letters, "Tank Hill" at the top of the tank. I think that "A" Company started at the top of the hill and "B", "C", "D", "E" and so on ended at the bottom of the hill. I was in "L" company. We were about mid-way on the hill. That means "M" company would have been next down on the hill. I am not positive about "A" company at the top of the hill or at the bottom of the hill.

Some of my instructors were from World War II. My barracks drill instructor was a PFC graduate from an earlier training group. He was sharp and he was rough on us, but he was fair. I had one run-in with him. We were marching to the machinegun range for the .30 caliber water-cooled barrel weapon. There was a jacket around the barrel that held water to keep it cool and prevent it from melting down from rapid fire. I was carrying the water can that contained the water to pour into the jacket. The weather at Fort Jackson was like most of the military posts across the country. The wind blew a lot at Ft. Jackson, and blowing through those tall pines it moaned. So while marching to the range, the wind was blowing hard and whistling underneath our helmets. He gave a left flank march. Due to the whistling underneath my helmet, I did not hear the command. I kept doing a direct ahead march. He threw his helmet at me and missed. I didn't say anything, just kept my mouth shut. Next morning while shaving in the latrine, he was shaving next to me. He rattled off a few words about it. I turned and looked at him and said, "You'd better thank God you didn't hit me." I figured I had had it, but he didn't hold it against me. I meant to bang him royally with that can. I had no more trouble with him. His name was Gross.

My field first sergeant was a SFC from World War II. He got wounded at the onset of Korea, and was sent back and later assigned to a basic training company. He showed us his bayonet wounds on his back. We took note of that. He carried a xylophone mallet around with him and used it to discipline. When we were in formation and at parade rest, feet about 36 inches apart, hands at the small of the back with finger extended and joined, we weren't allowed to curve our fingers or bend them. He silently walked behind us, and if he caught a finger or thumb curved or bent, he gave the knuckle a thump with that mallet. He caught me with my thumb curved. He tapped my knuckle and every nerve came alive in my body. While standing at parade rest today, I still remember to keep my fingers extended and joined.

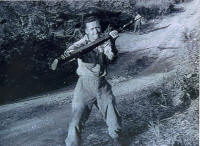

Basic training was from sixteen to twenty weeks of training. I had about eighteen to twenty weeks of basic training myself. We learned the nomenclature of all small arms that were in the military arsenal at that time. The films in the classroom showed assembly and disassembly of the weapons. Then we went through the assembly and disassembly of the weapons by the numbers. After classroom instructions, we went outside and practiced all of that in a training area. I was trained to use the .45 caliber pistol, the M-1 rifle, the .50 caliber machinegun, the .30 caliber machinegun, also the .30 caliber water-cooled machinegun (mentioned earlier), the M-1 and M-2 carbine, also the 57 recoilless rifle, which was a larger weapon. It took three to four men to carry it. It was broken down as barrel, tripod, and ammo bearer. There had to be precise training on this weapon. We functioned as a team with it. We trained on the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). The point man in a squad used it for rapid fire support. We also had to train on the use of the "grease gun," which was a type of weapon that men assigned to tank units carried. Also, we trained on the 60MM mortar, a three-man assignment: base plate, barrel and ammo carrier. We also trained on the 80MM. It took four to six men to carry it broken down. It was a larger weapon. We also were taught how to use a flame thrower and hand grenades. I was trained with strictly infantry training. We trained on the very dangerous weapon, the Bazooka--the one with the back blast. Extreme safety had to be practiced. Discipline was rigid because a mistake could cost lives.

The classroom films contained information on training hazards in the field, like snakes from the Pit Viper family, poison oak, poison ivy, poison sumac, and ticks. There were films on hygiene showing how to keep the body clean, how to treat blisters rubbed on feet from marching, and on how to recognize and deal with heat exhaustion or sunstroke. We learned how to care for frostbite and the general run of first aid. There were films on how to recognize the enemy that we would be fighting, and how to recognize their military vehicles and personnel.

Besides watching films, we learned about the Geneva Convention rules--how to treat prisoners and how we were supposed to be treated by the enemy if captured. The rules were not always followed in the realities of war. I feel that we got the best training that could be given at that time. Thank God for that. The small arms instruction that I had in basics has stayed in my mind all these years. I practice safety to this very day. I do not point a weapon at a person unless I intend to kill them. I don't believe in playing or joking around with weapons.

Our days were regimented in basics. First thing in the morning when it was time to wake up, the DI would put on the lights in the barracks and bang the wall. He said, "Let's go. Let's go." We had better hit the floor when he said that. We had only so many minutes to get dressed and fall out into the company street for roll call or head count. They checked to see if all were present or accounted for. If someone had gone AWOL overnight, that would be taken up by the company first sergeant and company commander. We were dismissed to go back into the barracks, make bunks, shave, and put the barracks in order. We also had to make sure the latrine was left clean.

Then it was off to chow or breakfast. We had about one hour to eat. Breakfast consisted of cereals, eggs, sausage, fried potatoes, milk, orange juice. We also had S.O.S., called by many GI's, "Shit on a Shingle." It consisted of gravy and ground beef poured on toast. I liked it myself. We did not have it every morning. Once a month, we also had cold cuts, the sandwich meats, vegetables, bread, milk, tea, coffee. There was no cooked meal that day.

After chow, we fell out for formation again. Sick call was given for those who needed to go. During work call, some were assigned to special details. Some had medical appointments. Our training was broken down into so many hours of certain types of training for that day. Maybe the first two hours were marching movements and formation. There were so many hours on the machinegun range and on all the other weapons. This progressed as the days and weeks went on. Basic military movements had to be first and foremost for the first three or four weeks of basics. A man had to learn how to march. It took about four weeks to smooth out a platoon or company, how to march smoothly, and finally precision toward the end of basics.

I already had some knowledge about rifles. My dad had taught me the safety and use of the .22 rifle, as well as the 12 gauge, 16 gauge, and 410 shotguns. He taught me how to hunt for small game like rabbits, squirrels, and quail. He taught me how to be a crack shot with the .22 rifle, and right aim with the shotgun. I qualified many times on the military firing ranges as expert and sharpshooter. (At retirement in 1991, I could still fire a deadly volley.)

Lights went out about 10 o'clock at night on weekdays and maybe at 11 o'clock on Saturday nights. Free time was spent cleaning weapons and writing notes home. Sometimes a platoon was sent to the motor pool for special detail or to clean weapons. Of course, there was guard duty. That came later on in basic training. A young trainee had to learn all of the basics of guard duty. He had to know all of his duty orders by number before he was put on guard duty. Guard duty was serious business in the Army. You didn't play around on guard duty. It is still the same today in the armed services.

Barracks were inspected each day while we were out training. (If those old barracks could talk, what stories they could tell.) If things needed to be corrected, we were told about it that evening during formation in the company area. If shortcomings in the barracks kept coming up, we had a G.I. party--cleaning in general at night after all-day training. We learned to keep our own area clean and orderly.

Sometimes we were awakened in the middle of the night for a special training instruction. That trained us to be ready any time day or night for anything that might come up, especially in combat--all of us. We trained to endure long hours. It paid off in combat.

Our instructors in basic training were strict and precise. If we did not do it right, we went through the exercise until we did get it right. And sometimes we got a lot of chewing out (or as they say in the military, "Reaming Out"). I think sometimes they used an auger or a brace and bit (ha ha) for the chewing out. There were times that I wished that I wasn't there.

At times the instructors used corporal punishment. It was given out to let us know that all of us had to work together as a team. We were taught that we could not accomplish the objective if we were divided. I found that so in combat. All must work together. One man's goof could cost several lives in combat. The instructor might give extra duty in the mess hall at night, or cleaning weapons detail, cutting grass in the company area, or extra drill ceremonies as punishment. Sometimes they gave Article 15--strictly restricted to the company area. Sometimes we were also disciplined as a whole platoon. The whole platoon would be taken on a night march, or restricted to the company area. If stealing took place in the barracks or in the platoon, caught or not caught, the whole platoon paid the price for one man's infraction. The lesson to be learned: You don't steal from each other. For the most part, you could have your money or valuables on your bunk and they were never bothered. Your buddy could also put his valuables under your bunk dust cover and not worry about them. Not so today!

We really did not have much discipline for doing wrong in my company. All of us tried to do what was right. I do recall one incident. One young fellow would not take a shower. He had a dirty neck and ear wax hanging out of his ear. So the word got to DI Gross. He said, "Men, you know how to take care of that. Give him a G.I." We asked him again to take a shower, but to no avail. One night we all crawled the infiltration course. It was wet and cold, and when we got back to the barracks, it was late. The fire had gone out in the boiler that heated the water to our barracks. I, like the rest, turned cold water on, and ran under the water for as long as I could take it. We all showered in cold water, but that one young man went to bed wet and dirty. He got sand all over his bed. That did it. Two or three days later, we told him to take a shower or else he would be G.I.'ed. He rattled off smart remarks. We threw him into the shower. We used a G.I. brush, G.I. soap, and some scouring powder. We rubbed the blood out of his skin. That helped for awhile. I ran into him in Korea. Same old thing: dirty neck, wax hanging out the ears. I don't know whatever happened to him.

I was never personally disciplined severely for anything while I was in basics. I made it a point to stay out of trouble. My mother and dad had taught me to do right. I remember one humorous incident, however. DI Gross assigned me to buff the first floor of the barracks. I told him that, being a country boy, I had never used a buffer. I probably would tear the wall out. He said, "Get hold of it. You're going to learn how to use a buffer." So I did. I thought it would tear out the side of the walls, along with the upright support beams. He did not get mad at me. I learned how to use a big buffer, and I think about him today when using one.

Church was offered in basics. We were called into formation and marched to the chapel. The chaplain delivered messages on morals, ethics, discipline, and problems that we would face away from home while in the Army. All of us had to take advantage of worship on Sunday, because we were required to attend. That was military regulations at the time. The instructors did not breathe down our necks while we were there, but they did keep eyes on us to make sure that we did not nod off to sleep. If a soldier did nod off to sleep, one of the DIs would tap him on the shoulder and motion for him to stay awake and pay attention to the chaplain. They were not rude about it. When we marched out of the chapel and back into formation, they encouraged us to pay close attention to the words of the chaplain.

Besides church, there were "Character Guidance" subjects and classes given in the 1950s and 1960s on the moral and ethical problems we would face. There were classes and films on moral issues and how to possibly solve them. Sometimes they asked a question on how we would solve a particular question or problem. (I called them hanging question marks.) Sometimes these classes were held in the chapel by the chaplain, and sometimes the classes were held out in the field by trained instructors. These types of classes were done away with later in the 1960s. Many of the subjects and classes helped me.

Fort Jackson, South Carolina, was sandy with tall pine trees. It got hot in the summer and cold in the winter there. Thunder storms were heavy in the summertime, and there were ticks, chiggers, sand fleas, sand flies, mosquitoes, snakes, poison oak, poison ivy, and poison sumac. Most the basic training posts in America were that way, I believe. There were always some animals around the field training area. There were deer, fox, skunks, and opossums. They always caused trouble for the basic trainee or DI or whoever. There were certain fevers caused by ticks. They included the Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Q Fever, Lyme Disease, and Tularemia. The swamp areas had the snakes: cottonmouth, rattlesnake, copperheads and coral snakes from the pit viper family. Chiggers could cause bad trouble if they got on and buried into your skin, particularly at the top of boots and around the waist. They could cause solid sores. Today the Army has good repellent for this.

Toward the end of basic training, we had to qualify in a proficiency test--a test that was given on the weapons that we trained on. If passed, we were assigned to the infantry. As I mentioned much earlier, at the entrance of basic training, we had to take a battery of tests to see which field of service we best fit into, such as supply, infantry, electronics, transportation, chemical field, and others.

We also had a certain amount of fun in basics. At times the physical fitness tests and exercises were funny. Competing against your buddy, trying to get everybody in unison, the shape and position some got into--you couldn't help but laugh. The hardest thing about basics was hoping to do everything right. There were so many things to learn in a short period of time.

There was a ceremony after basic training was over. We spit-shined boots, got uniforms in top shape, and had a company parade. We marched past the grandstand on the parade field. Some trainees' folks got to come and see their sons graduate. What a beautiful scene: a battalion of soldiers on a parade field, passing in review.

I left basic training feeling that I had been trained to fight, but I can't say dogmatically that I was as prepared as I would like to have been. I was stronger physically, quiet and reserved, and my head had been trained to accept life or death, because I knew where I was going next. I came to appreciate my instructors after I got to the combat zone of Korea. I thanked God many times for them and the rigid training they put all of us through.

Some men could not take basic training because they could not physically take it. Some could not take it mentally. There was one in my platoon that went AWOL while in basic training. His last name was the same as mine. I did not know him. He was from Georgia, but I don't know what part. We were in the sixth or eighth week when he left and I never did see him again. I don't know why he left. Probably he just couldn't take it. It takes guts to be a soldier--especially a career one.

I went home on leave after basics on a 10 or 15-day delay enroute. I visited my loved ones and dated some. I wore my uniform while at home, and the townfolk always made comments on the uniform and how fine I looked in it. We did not talk much about the war when I was home that week. My mom and dad didn't know anything about Korea. They didn't know where the place was. Yes, my folks were concerned about me and my safety. I am sure that they thought that I could be killed. Any man headed into combat who is not concerned is either an idiot or a fool. There is a gut feeling that only those who experience it can understand. Two combat soldiers can relate to each other. I have never met a civilian who I could relate to about the gut feeling of walking into combat.

After leaving home, I went to Nashville, Tennessee, on a Trailways bus. I went to the Nashville airport and boarded an airplane for Fort Lewis, Washington. I remember two things in particular about the flight. We flew over the Rocky Mountains. That was an experience for a country boy. I also remember the plane hitting air pockets.

At that time, we were at war. I had no other training in the United States. My country said go - and I went. My advanced training took place in the battlefields of Korea.

I left for Korea the last part of December 1952. The name of the ship that I sailed on was the Marine Lynx. It was a one-stack job. It was a troop ship, and only operating personnel were in charge as best as I can remember. I think it could carry about 1800-2000 personnel - maybe 2,500. I think that only Army troops were on it. We were packed like sardines, and I think we were escorted by submarine. I could be corrected on that. Only people were transported on the ship as best as I remember. Naturally, food supply had to be transported.

I had never been on a ship of any kind, but I didn't get seasick - at least not going over. I got sick coming back because of my stupidity. Many others got sick going over. Men have died from seasickness. There is no way that I can relate to you unless you have experienced it the vomit, the smell, and the misery. There is a smell that I cannot describe when men are vomiting all over the place - in cans, over the rails, wherever. I thought that the young man that bunked above me was going to die. I helped him all I could. He made it.

We ran into a hurricane or a cyclone, and I thought all of us would be killed before we even got to Korea. It was so bad that everything had to be tied down and locked tight. The only person who could go on deck was one of the ship personnel, and he had to be strapped into a harness and guy line tied inside to pull him back inside. I had never heard such moaning and squeaking out of steel in my life. We looked like a rubby-dub-dub floating in the Rocky Mountains. That shook me up for sure. However, I also remember that when the weather was good, it was a wonderful pleasure to be on deck and see the dolphins and porpoise play alongside the ship and then pass and leave us doing 17 knots. That was a great thrill to this ole country boy.

On the trip, there was card-playing for entertainment, as well as writing letters, telling jokes, and getting to know men from all walks of life and finding out what states they were from. I didn't know anyone on the ship. There were movies shown on certain nights. We had chapel service. We could check out books for reading pleasure. So there were quite a few things to do -- and there was duty to pull, also.

We crossed the International Dateline, but there was not all that much to it. The ship's commander came over the PA system and told us that we were crossing the dateline. I think he mentioned the beautiful mermaids and dragons of the sea. Then we were issued a wallet-sized card with mermaids and dragons on it, with the name and date that we were initiated into a certain order. I carried mine until I wore it out.

The only duty I caught going over was for the most part cleaning the latrine and helping to keep the bay clean. I also had to keep my own area orderly and clean. That was about it for me. Many others pulled a lot of details going over. I caught mine coming back home.

We did not sail straight to Korea. We docked at Yokohama, Japan, on Tokyo Bay in Central Honshu. It took 18 to 20 days to get over there. Once we arrived, military personnel were vehicled out to Camp Drake, Japan, from Tokyo. We hand-carried our records with us. Our 201 file was checked and we were assigned to a division. I was assigned to the famous 2nd Infantry Division--the ole Indian Head.

From Camp Drake, Japan, we boarded a troop train and rode across the country of Japan. Then we boarded a ship at another port for our journey to Korea. We arrived early afternoon at Inchon, Korea, about the middle of January or first of February in 1953. We were slowly taken off the ship and transported to a staging point where we were assigned to different companies of different divisions--like the 2nd Infantry Division, the 24th Infantry Division, the 3rd Infantry Division, the 25th Infantry Division, and others. My first impression of Korea was that I had arrived in a war-torn country that had been destroyed by artillery, bombing, and other large weapons. I could tell upon my arrival that we were in a war zone. Just about all of the homes and buildings had been destroyed. War is Hell. It just destroys. Period.

From Camp Drake, Japan, we boarded a troop train and rode across the country of Japan. Then we boarded a ship at another port for our journey to Korea. We arrived early afternoon at Inchon, Korea, about the middle of January or first of February in 1953. We were slowly taken off the ship and transported to a staging point where we were assigned to different companies of different divisions--like the 2nd Infantry Division, the 24th Infantry Division, the 3rd Infantry Division, the 25th Infantry Division, and others. My first impression of Korea was that I had arrived in a war-torn country that had been destroyed by artillery, bombing, and other large weapons. I could tell upon my arrival that we were in a war zone. Just about all of the homes and buildings had been destroyed. War is Hell. It just destroys. Period.

I was assigned to the 2nd Infantry Division back at Camp Drake, Japan, but not to a company, regiment, platoon, or squad. That was done at the staging point after getting off the ship in Korea. I was assigned to B Company, 2nd platoon, 1st squad, of the 9th Infantry Regiment, 1st Battalion, 2nd Infantry Division. We were transported to our outfits by trucks, half tracks, Jeeps, and some by tanks.

My regiment was at Pupyong-ni. The men in the 9th Regiment had pulled back from the front lines for some training and replacement troops. The subjects taught during the training were basic military subjects, such as map reading small unit tactics, use of the compass, foot marches, and soon included attack and defense problems on the snowy hills, made more realistic by the rattle of machineguns and the crump - crump of the mortars. You can never forget the sound of it.

I was briefed about the critical situation of combat and told that I would be pulling guard duty. Guard duty was very serious in combat situations. To slip up there would cost lives. The North Koreans were very good at slipping through the lines. At times some of the companies found a man with his throat cut while sleeping in his sleeping bag. That's why guard duty was such serious business. I was fortunate to get some of this training, because it prepared me more for the weeks ahead.

I did not complain about the position and job I was assigned to do. I was taught in basic training to obey orders, and that is what I did. The young soldier is quite different today. (The Special Forces don't have that kind of problem today. They are close knit.) Morale had to be kept at a high point for efficient operations. I always did my job to the best of my ability, and it paid off.

At this point, I met a sergeant that was from my home town. I did not know him, but I did know his sisters while in high school. He found out I was from Tennessee, and asked what part. I said Baxter, and he said, "I am from Baxter also." We hit it off. He asked me what weapon I had been assigned to. I told him the 57 Recoilless Rifle. He said that he thought he could get that changed, so he did. I was assigned to his squad and the 60mm mortar. I gunned on that weapon until I left Korea. This sergeant was Ridley Cole. He took me under his wings and taught me the ropes. I have thanked God for him many times down through the years. I was a replacement soldier, and Ridley was one of the seasoned combat soldiers in my company who helped me when I got to it.

I was apprehensive about going into combat. If I had had advanced basic training, I still would have been apprehensive. I think any man living has some fear of dying, I don't care how much hot air he blows through his nostrils. He still has fear. Like I said earlier, there is a gut feeling that only a man walking into possible death can know. I cannot relate this feeling to anyone reading this memoir, nor can they know it or feel it unless they are walking into possible death. It is easy to blow hot air, but when walking into combat and maybe death, there is no hot air blowing. Some of the biggest men that walk upon the face of this earth prayed and ate dirt like I did, saying, "Oh God, get me out of this mess." I think I can truthfully say that there are no foxhole atheists.

The weather when I arrived in Korea was cold and wet. I remember training in rain, ice, snow, and the rice paddies. Not long after I got in country, the weather went into the rainy season called monsoon. And I mean it rained in downpours. Several weeks of this went on. Spring came and the rain tapered off. Then it was summer. Summer got hot in Korea--up to 105 to 110 degrees and humid.

We were in the hills, valleys, and mountains. The hills and mountains in Korea looked like the Smokey Mountains of Tennessee and the Rocky Mountains of the west in our country, but they were maybe higher. I was so high in the mountains in Korea that I had a feeling I cannot explain looking down into the valleys and rice paddies. There was some vegetation--trees and shrubbery, although much had been destroyed by bombing, artillery, and the dropping of napalm. Napalm burned and destroyed vegetation. I remember that there were azalea in Korea on the mountains. One of the most beautiful scenes I have ever seen was when they were in bloom in the spring of 1953 and 54. They were pink, red, and white. I wish I had a color picture of them, but I don't.

After the training, we headed for the Kumwha and Chorwon Valley up in the north. I came close to losing my life in the valley near Hill 1062 known as Papasan--Pike's Peak Hill 597.9. I also served in the Boomerang sector. I have never been so cold in my life as I was during those following weeks in Korea. At night the temperatures were 40 to 60 below zero. I was so cold I just about wanted to die, but I kept fighting on. I hope and pray anyone who reads this memoir never has to be that cold. Some of this cold is being experienced by our men in Afghanistan now. I can relate to it.

I saw the enemy about two or three weeks after I got over there. Through field glasses we could see them throughout the day. The Forward Observers (F.O.) could see them day and night. They were positioned out in front of everybody else on listening posts where they could warn us of an attack and enemy movements. The first round of fire I came under was in the Kumwha Valley. The Communists threw everything they could at us, I think. We had to retreat about two miles and re-group. I don't know how many men were lost at that time. I had a close call that round.

Since I was assigned to a 60mm mortar, I did not see as many dead as the riflemen did in front of me. We fired over the heads of the front lines, and killed men who never did get to the Main Line of Resistance. After about two or three weeks on the front line, I could see the helicopters lifting out our wounded and dead every day. Our helicopters were small at that time. We called them the "Bumblebee." They could lift out three and four at the most at one time. Oh, what a great difference today. So many more lives are saved.

We never liked seeing the dead, the wounded, or the dying. I do not like seeing a dying or dead retired veteran today. I hold a military funeral from time to time here in Nashville, TN. There is a gut feeling that I don't like. Seeing the dead, you cried and wept, but you carried on. All the mental agony came later. Later, many went out into twilight zone and never came back to reality. I have so far had only a few flashbacks. As I get older, that may change. I pray not.

My first few days on the front lines were spent digging trenches, building bunkers, and stringing barbed wire. This was done many times with incoming mortar and artillery rounds dropping all around us. Many were killed doing this kind of work. You did not have to be in hand-to-hand combat to be killed. One afternoon, my company was in a valley in the Chorwan Valley area. It was sometime in April of 1953, just a couple of months after I arrived in Korea. The enemy was on the forward slope of a hill to our left. My squad and company were in the valley and we were very visible to the enemy. They opened up on us with heavy weapons, mortar and artillery about mid-afternoon. They blew up a water trailer that I was standing near. There were only eight or ten steps between me and death when that happened. Their fire was heavy and deadly, and we knew that there was a possibility that most of us would be killed if we didn't take cover. We were ordered to withdraw, re-group, and prepare to advance on the same position again.

I made a misjudgment while trying to find cover. I ran into a decline that had barbed wire in it. I got tangled in it, and that slowed me down and almost cost me my life. Although rounds were falling all around me, I managed to get out without a scratch, but for a while there, I thought my time had come. By the grace of God I made it out of that one, but wondered if I would make it through the next one. I do not know how many men we lost that day, but I do know that I did not lose any of the men in my squad. Our squad leader ran out on us that day, leaving ten of us to find our own way out. When we regrouped, I felt like killing him.

I saw the Air Force planes bombing the enemy and strafing them. I highly praise the Navy for the accuracy of their big coastal guns (or weapons) that they used to prepare a hill or mountain for us to go in to. Many lives were saved because of them. The spotter planes dropped red or yellow smoke bombs on the enemy, and the Air Force did the bombing. A lot of time, our artillery was also called in.

Although I was new to combat, emotionally I held up well. But I did have times of fear, always wondering, "Am I next? Will the next round get me? Will a sniper pick me off?" The thought of stepping on a trip mine was always there, too. As I said earlier, only a fool or an idiot would not have fear in a situation like that.

I was armed with an M-1 carbine, a .45 pistol, or M-1 rifle, six to eight grenades attached to the field gear, and a gas mask. I had to be armed while gunning or manning the 60mm mortar. If I were to be overrun, I could defend myself--live or die.

In Korea, I learned "on the job" that we as men had to depend on each other. That meant trust. I might be the one that could keep my buddy from being killed. He might be the one to keep me from being killed. You paid close attention to all orders of operations and instructions. We had to make sure that our weapons were operational at all times. A faulty weapon could cost lives.

During my first three months in Korea, my company stayed in one place for four or five weeks. We moved and set up operation, and then maybe we would be ordered to replace a tired and fatigued unit. We were in danger most of the time. We never knew what was going to happen next. The North Koreans picked certain units and hit them, with all hell breaking loose when they did. Sometimes it would be us and sometimes it would be one of the other companies they hit, so there was a high state of alert at all times. That was something you did not learn in basic training.

There were nine to eleven men per squad and there could be from forty to forty-four men per platoon if it was all full strength. But due to combat, there was usually less men than were needed. Only when first committed to combat was the platoon up to full strength, and even that did not sometimes hold true due to the shortage of trained men. Replacements did not always come easily.

There were nine to eleven men per squad and there could be from forty to forty-four men per platoon if it was all full strength. But due to combat, there was usually less men than were needed. Only when first committed to combat was the platoon up to full strength, and even that did not sometimes hold true due to the shortage of trained men. Replacements did not always come easily.

There were eleven men in my squad. I was assistant gunner on the 60mm and a big black soldier from either North or South Carolina, who was over six feet tall, was gunner. The gunner set the sights for firing the weapon. I proofed him on the setting and then we waited for orders to fire. There were two or three men who were ammo bearers. They carried three to six rounds on a pack board, depending on how much ammo was at hand. Orders to fire most normally came from the company commander through the first sergeant to the platoon sergeant and to the squad leader--then fire weapon.

In the heat of combat, it did not always work that way. Sometimes we had to fire at our own will. If the gunner got killed, it would be my duty to step into his place. If I were killed, the ammo carrier would have been the person who stepped into my place. We were all trained to operate the 60mm. The other men in the squad were placed as support or guards around the 60mm.

The 60mm supported the line company and the line platoon. A platoon of 30-44 men could have two 60mm per platoon. I am not sure how many were assigned to a company. There were one or two 57 recoilless rifles to a company for support. It was a heavy weapon that was broken down and carried by four to six men. If there was a shortage of weapons, you made out the best you could with what you had, and prayed to God to survive.

The various weapons we used were: 60mm, 57 recoilless rifle, M-1 rifle, M1-2 carbine, .45 pistol, and grenades. The 60mm was broken down into three pieces--base plate, tri-pod, and tube. It was carried by three men. The 57 recoilless rifle was broken down into two pieces--barrel and tripod--and carried by four to six men. It was a very heavy weapon. The gunner and assistant gunner for the 60mm picked a spot for it to be set up. We would not set up in open space or on the forward slope of a hill if it could be avoided because the enemy could spot us in open space much easier than if we set up behind a hill. We didn't want to be sitting ducks for the enemy.

Ammo carriers helped prepare to set up the weapons. The ground had to be leveled. No trees could block the flight of the round fired. We had to have an opening so that the round we fired could have free flight in an arching pattern. A short round could kill several of your own men and a tree in the line of fire could cause the round to detonate or explode in flight. We could set up behind a small hill and fire over it. That way, we had more cover and protection.

We worked with the 57 recoilless rifle the same way. All the men in the squad helped to set the weapon up if they could, but the gunner and assistant gunner and ammo carrier did most of the setting up. The gunner set the sighting and the assistant gunner checked to see if it was correct. The ammo carrier placed rounds to be fired near the assistant gunner. The assistant gunner prepared the round to be fired. When the rounds were ready, I tapped the gunner on his steel helmet and said, "Ready." The gunner said, "Fire Round One." I replied, "Round on the way."

The 60mm and 57 recoilless were easy to fire, but they were very dangerous. The 57 recoilless had a back blast, so we had to be careful of that. Nothing could be in the way behind. We were quick to adhere to all the safety precautions. Still, there were other difficulties that had to be surmounted with the use of these weapons. Because it took more than one man to carry the various parts, if just one got separated from the others, it created a problem. The three men carrying the 60mm mortar in my outfit did not get separated. We were fortunate to stay close together.

The tube or barrel of the 60mm could be fired without the base plate and tri-pod. You could place the tube on solid rock, hold the tube between your legs while sitting down, and elevate it by hand and sight. It worked, but it was very dangerous to do that. If it is a live or die situation in combat, men will do what they have to do. In a rice paddy, you couldn't fire it that way. The water and softness of ground hindered firing the weapon.

The 57 recoilless rifle could be fired at almost ground level, providing you had open range, but not so with the 60mm. There had to be clearing above so as not to block the flight of the round. It had to arc to its target. The distance of the 60mm round was determined by powder increments attached to the round to be fired. Not so with the 57 recoilless rifle. It fired a shell-cased round. The 60mm could be carried into firing when the enemy approached too close to the line troops, or whenever else it was deemed useful or necessary.

Prior to joining the 60mm platoon, I had been trained on the 60mm and the 57 recoilless rifle at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. In Korea, I learned that the biggest problem with the 60mm and the 80-81mm was preparing position to fire. If possible, 180 degrees had to be selected for setting up, and sighting could be very delicate. You did not want to fire upon your own troops, so sighting had to be accurate. Once positioned, firing orders and directions came from the forward observer (FO) at an outpost. An outpost or "listening post" was in front of the line troops. The FO gave firing orders (coordinates and azimuth on firing direction) to the company CO, and then they came down to the squad and platoon. The platoon sergeant gave the squad leader orders to fire so many rounds of HE or WP.

Weapons did not function well if they were dirty or rusty from rain. Weather-related problems also resulted if the weather was 40 to 60 below zero. The weapons froze up. The M-16 of today is even more sensitive. Ask the Vietnam vets about it. I trained on all from M-1 rifle, M-14, and M-16 rifles during my career. As far as I am concerned, the M-16 was the most barbaric weapon in the military arsenal for small arms.

While on duty in Korea, I had a misfire or a round that failed to fire. This could happen to something as seemingly small as a broken firing pin, faulty ammo powder (damp or too old), or a worn tube, but the results could be disastrous. A worn tube could cause a round to fall short and kill some of your own men. It happened. Also, to take a misfired round out of a 60mm was very dangerous. The tube had to be taken loose from the base plate, but not loose from the tri-pod. The base of the tube had to be lifted upward slowly while the assistant gunner had both of his hands holding around the top of the tube, thumbs and forefingers circled so that as the round slowly slid out, it slipped into circled fingers without the plunger hitting your fingers. If the plunger was activated in the round, it could explode. You could kiss all of it goodbye. Some men became nervous and let the round slip out of their hand. It then would explode. Sometimes a round could fall out of the hand and still not explode. While taking out a misfired round, I thought about eternity and the next world, and I did some praying also. Again, any man who says he didn't pray while in combat in Korea is a lying fool.

The rounds for the 60mm were the same size, but I don't remember their weight. There were three types of ammo used: High explosive (HE); White phosphorus (WP); and Smoke. HE rounds exploded and shrapnel flew in all directions. It could be set for air burst or ground burst. WP could also be set the same way, but it was especially effective when you got an air burst that spread over a wide area and fell onto the enemy. White phosphorus could burn through a body, burning the enemy (or ourselves) alive. Only stopping the air to the phosphorus would stop the burning. A handful of wet mud placed over the spot could help extinguish it, for instance. Smoke was used for cover under enemy fire, and it was very effective in combat. Many lives were saved due to smoke coverage during combat.

The 80 or 81mm mortar, which were a level above the power of the 60mm mortar, used much bigger rounds, but they were fired on the same principle as the 60mm, and used the same type of ammo. Artillery rounds were bigger, and the Navy used big guns on the coasts to support troops in combat. The rounds they fired were huge. They did a good job supporting us, and so did the Air Force. Today, the fire power is much greater and more advanced due to the use of helicopters and the weapons in them that were designed especially for supporting ground troops.

If the weapons broke down for some minor reason, generally the gunner and assistant gunner could repair it. But if a major repair was needed, such as a worn tube or barrel or the sighting levels had a problem, they had to be repaired by the trained armorer. These specially-trained men were assigned to repair small arms in a unit. A trained armorer was an integral part of all artillery units. Some of them were assigned permanently to units and some of them merely visited units to repair weapons. The armorer was a very important soldier in the Army during the Korean War.

Normally the tube or barrel had to be replaced if it was defective. Also, the tripod could become so damaged that it had to be replaced. New firing pins had to be made to replace defective ones. There were some spare parts on hand, but if they weren't available, they had to be ordered through supply channels. Supply had its own section for weapons maintenance. Sometimes supplies were not easy to come by. So many units requesting repair parts at the same time could cause a shortage. This could be very dangerous for combat troops and units.

During my time in Korea, I was mostly up in the Kumwha and Chorwon Valley in a section known as Boomerang. Hill 1062, better known as Papasan, and Hill 597.9, Pike's Peak, were located there. At times, we were in some hill locations, but these were mountains, not hills. I was north of the 38th parallel, and then later south of the 38th.

In the Boomerang sector, we were always digging in or fighting, building bunkers and setting weapon positions, stringing barbed wire, or preparing for the next fight or possible fight. One that stands out in my mind most vividly was in the Kumwha and Chorwon Valley near Papasan. We were attacked from our front in the afternoon. We were hit so hard that we had to move back for about two miles. That one almost cost me my life, and yet, by the grace of God, I did not get a wound. A water trailer was blown up so close to me, only a small bunker saved my life. You could put both fists in the holes that were blown into the trailer. I don't know how many men we lost that afternoon.

We also guarded the tungsten and coal mines in Sangdong-Yongwol. We relieved the 160th Infantry of the 40th Division. This job of security was so critical because it could have been blown up at any time, but it wasn't. The material that came from these mines was used for explosives, in ammo, and for other uses. The danger was that we expected sabotage or possible bombing of the mines. All of us guarding were very sensitive to the danger of our assignment. All of my company was involved in guarding the mines. I don't remember the size of the mines, I just know they were large. We were armed with the M-1 rifle, the .45 pistol, the M1-M2 carbine, and the BAR. We also had the 60mm and the 80-81mm artillery positioned in case of needed support. The grease gun that the tank crews carried were used, too. The grease gun fired the same size of ammo that the .45 pistol fired, only it was a larger weapon than the .45 caliber pistol.

The guarding hours of duty at the mine was 24 hours a day, two hours on and two hours off if the company was up to strength. It if wasn't, a shift might run twelve hours on duty. I was a guard there in the early part of 1953. I remember that one of the problems of guarding the mines was that some villages were nearby and some of the women made their rounds to offer their services. Our orders were to not accept the services of these women. I don't recall any serious happenings with that, although I'm sure that some soldiers found a way to oblige.

At times, we had a change of command in my company. I don't recall that much about it. I was concerned about staying alive, and it didn't matter that much to me. Most of the officers in combat made good leaders, although sometimes you had a rinky-dink.

The Thailanders were attached to us. They were good fighting troops who were not afraid. We also had the Turks from Turkey. They did most of their fighting at night with knives and machetes – silent death. They were friendly, but you left them alone. The French were there. They did their part of fighting. The Canadians from Canada were there also. I think we had soldiers from Australia, too, but I could stand corrected on that.

Most of the enemy soldiers were young, although there were some older ones in their ranks. They fought well, and although they fought in the day, it seemed that they fought more at night. They doped up and came with a yell. They were armed in much the same way we were--small arms, hand grenades, and artillery pieces. They were very accurate with their weapons and because of that their weapons ere effective. They had a lot of dud rounds in their artillery that did not explode. They must have had poor powder for their artillery and mortars. Thank God for that. My company (B Company of the 9th Regiment of the 2nd Infantry Division) never suffered extreme casualties during the months that I was with it. Unfortunately, other companies did.

No one in my company was taken POW that I know of while I was serving in it. We managed not to be taken or captured. There was always concern about being captured--how will I take it? Can I stand up under the torture? Will I break? Even fear crosses the mind. You didn't talk about it. You just waited to see what happened. You only carried your dog tags and the Geneva Convention card on your person, so you see, they had to use torture to pull information out of you. I won't say what I would have done if I had been captured, because I don't know. I won't blow any hot air about it either. By the grace of God, my time did not come to be taken POW.

We merged South Koreans into our units and trained them to fight as we Americans fight. They made good soldiers. They now have a tremendous army today. Their "White Horse" division fought in Vietnam and racked up some outstanding history. The American soldier is probably the greatest fighting soldier in the world, unless it would be the Turks and commandos of Israel. I’ll leave that to the historians to decide.

I was fortunate to have never lost any of the men in my squad. I know the company lost men, but I don’t remember who. I also don’t remember the names of the medics who were in my company. They just did their job and they were good at it. A good medic was loved by most of the men in a company.

The weather in Korea got cold in the winter. It was 40-60 degrees below zero sometimes, and as mentioned before, that kind of cold weather could cause your weapon to malfunction. In the spring it rained like monsoons. It got hot in the summer, but the fall was pleasant. The flowers were beautiful in the springtime. Above all, however, the cold of Korea remains strongest in my memory.

We wore our regular fatigues and regular underwear spring, summer, fall and winter. For very cold weather we wore long handled underwear, our regular fatigues, and then over them we wore a cold weather pair of lined trousers made strictly for cold weather. The wool sweater could be worn under the fatigue jacket, our field jacket with liner, and parka lined with fur which was very warm. We also wore head gear that was helmet liner, steel helmet, and a pile cap underneath which was made of wool and polyester. That was also very warm. We also had a wool scarf that we wore around our neck and over our mouth and nose. I have had icicles hanging down from my scarf five or six inches from breathing moisture through the mouth and nose. I pray to God that anyone who reads this memoir never gets that cold. I got so cold that at times I felt like dying, but I kept pushing on. Forty to fifty degree below zero weather didn’t make it easy. It was common for the temperature to drop that low at night in the northern part of Korea.

For the footwear we had our regular combat boots that we wore in basic training. They were leather. As long as you kept moving you were okay, but if you had to stand or sit for long, your feet would freeze. I came close to losing my right foot from the ankle down, and my right leg from the knee down. I kept moving and would not give up so I did not lose them. I have a circulation problem in them now. The mountain boot was issued to us while I was there. They were thermal and lined so air could circulate inside the boot. That was a great improvement. If you stood in water, snow, or ice for too long, you could get trench foot. Your feet could literally rot off and make it necessary for amputation.

I was sick in Korea. I had dysentery so bad that I passed blood. It was rough. I also had an impacted wisdom tooth cut out. I thought I had been kicked in the head by two mules. My jaw looked like it had two golf balls inside my mouth. My buddies always liked to joke around about things like that.

When we were on the front line, the 1st Marine Division was to our right flank and we had field radio contact with them, as well as messengers, I think. The Marines are one of the elite fighting outfits in our military make up. They will fight to the last man. They were fighting to stay alive and hold ground as the 2nd Infantry Division was trying to do.

We had some tank support but our greatest support came from the artillery a good distance to our rear. The 105mm weapons mounted on jeeps gave us much-needed support at times. This 105 was mounted on some tanks also. It was larger than a 80-81mm mortar, and fired somewhat like the 57 recoilless rifle.

When we dug in for the night, we dug as good a foxhole as we could in a line or half moon shape. We set up our mortars and 57 recoilless weapons and positioned the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) for support. Then we positioned the riflemen, strung barbed wire, and tied tin cans to the barbed wire. When the enemy got into the barbed wire, the cans rattled and the lead would fly. Many times night vision equipment would tell if enemy or animals were in the barbed wire. A flare was sometimes shot from the mortar and an air burst would light up the area and give information on what needed to be done. There was no lighting cigarettes and no flashlights unless you were covered with a blanket where it could not be detected by the enemy at a distance. We had some infra red equipment, but not like today's. We set up a listening post out front. What was detected by the guard at the outpost was passed on to us, then we decided what to do from there. The terrain always played an important role where and how we would set up also.

Sometimes civilians became problems to units if they were close to towns or villages. If the women gave the come on or were willing to sell or give away that "Booger", there were soldiers that wouldn’t turn it down. Children could be a problem begging for food. Stealing could and did take place. You had to set up tight security.

We saw helicopters used by other units to take out their wounded and dead. They flew over us almost every day and sometimes at night after a heavy fire fight. It was strange how the North Koreans and Chinese soldiers would attack some units more than others. It is a sound you never forget when a battle takes place across the hill or down the valley from you but they don't attack you. You know all hell has been let loose on some other unit. Some of the companies in the 9th Regiment lost almost all of their men. Somehow my company was spared of that.

I had never worked with blacks before I worked with the black gunner in my company who was from South Carolina. My first contact and working with blacks was in basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. I did not know what prejudice was, let alone to feel prejudice. I was just a plain ole dumb country boy. We had a few blacks in my company. If there was prejudice or dislike from whites toward the blacks, I did not notice.

I do remember one black soldier from Chicago who was a mean rascal. He would not take orders from anyone. I do not know what ever happened to him. A platoon or company of soldiers does not like troublemakers. I do know that the black soldier served well in combat in World War I and in combat in World War II, and after reading some 70-75 volumes on how the military role helped win the American frontier west, I know that the black soldier has played an important role.

While on the front line, we did not get to wash and shave very much. We filled our steel helmets full of water out of a rice paddy, small creek or large stream, and washed off as best as we could. The soldiers called that a "whore's bath." Sometimes we bathed in small streams and rivers if they were nearby and safe. I went for weeks without a bath in Korea. When we were pulled back in Reserve, we could get a hot bath or shower and change of clothes. There were shower points set up for that.

On line, we washed our clothes in a rice paddy, and sometimes we washed the small clothes in the steel pot. When we had the chance, we washed our trousers in a creek, river or rice paddy, then laid them out on a flat rock and used a smaller rock to pound the dirt out. In Reserve, we exchanged our dirty clothes for washed clean clothes, hoping that we would get the right size. Unfortunately, it didn't always work out that way. Sometimes we ended up with a size or two too big, but at least they were clean.

Shaving created a problem because when we were in combat, heating water was not an easy thing to do. Starting a fire to warm the water meant there would be fire and smoke. This could give a position away to the enemy, but some did it anyway.

While on the front line, we ate C rations out of a can. These pre-packaged meals consisted of corned beef hash, sausage patties (so greasy that most of us did not like them), beanie weenies (beans with franks cut up and mixed in with the beans), spaghetti and meat balls, and canned fruit (pears, peaches apricots and fruit cocktail). We were issued packets of food that consisted of one can of the meat type mentioned above, one can of fruit, a plastic spoon, a package of coffee, sugar, salt, crackers, chewing gum, and a few other items.

The food we ate in Reserve was different. We had cooked rice, potatoes, vegetables, chicken, ham, bacon, eggs, pork, and sometimes pie and cookies. It was always a treat to get a hot meal. We even got one occasionally on the front line. It was sent to us in marmite containers that kept the food hot. What a treat!

We were instructed not to eat the native food because it was raised where they used human manure to fertilize the potatoes and other vegetables. I did not eat vegetables that were grown in the ground. Some of the soldiers did and as a result, they got intestinal parasites and dysentery. But I did eat some peaches from the trees and some of the finest chestnuts I ever did eat. I ate them because I knew that there would be no harm to my body (which there wasn't) and because I liked them. Those chestnuts and peaches were the best things I ate in Korea. I got them because we were going through the fields and orchards when they were ready to pick. The stateside food I missed the most was my mother's cooking. She could cook green beans and potatoes and corn bread like no one else I knew. I also missed a good old hamburger and milkshake, as well as a moon pie and R.C. Cola.

Life in the Army in Korea also was a time to make friends. I became good friends to two buddies while I was there. One was a guy named Whaley from Kentucky. He played guitar and so did I, so we hit it off. We took turns playing the guitar that we had. The other fellow was Murphy. I think he was from North Carolina. He liked to hear me play the guitar. We had to use commo wire to string the first two strings on the guitar until someone in our company went on R&R and maybe brought us back a set of strings. All three of us loved country music. As far as I know, both of them came back home safely. I have not heard from them all of these years since I came back.

Although war was always serious to us, we tried to have lighter moments and the guitar helped supply them. We picked some country music when in Reserve, told some jokes, and sometimes read our mail to each other. We told about our families and tried to balance it out. That is how we dealt with being in a combat zone.

Mail from home always helped. At first I did not get my mail, but when I did finally get it, it was tied up in a bundle, there was so much of it. I was glad to get it. My mother and my sisters wrote to me, as did a girlfriend in Missouri. I asked her to wait for me and we would get married when I came home, but while I was in Korea, she wrote a Dear John letter to me. At 11,000 miles from home and in combat, a Dear John letter will un-gyro your head. There was one soldier in my company who was thinking about re-upping in the Army. When he wrote to his wife in California to ask her about the matter, she wrote back to him and said, "If you do, don't come home to me and the children." He shared the letter with me. It shook him up and he rotated home.

Packages from the States were a great morale booster. We got packages from home with cookies and cakes. Some came in good shape, but some were also crushed and stale. The fruit cakes seemed to make it okay. Cookies and cakes were generally shared with each other. I asked my mother to send a cross on a chain to me so that I could wear it around my neck. My sisters picked one out and mailed it to me. I wore it for a long while. When I came back from Korea, I became a Christian. I don't wear crosses today around my neck or on my body. My Lord and Savior Jesus Christ bore the cross for me and I don't feel worthy to wear one.

I attended worship in Korea whenever I could. Services were held in a field setting out in the open. My mother had taught me to go to Sunday School and church. I drifted away from it while on the road in show biz, but I did read my Bible in Korea. Chaplains visited us when they could. Sometimes there were not enough chaplains to go around. During combat one chaplain might have several units he had to visit. It is different now. Today there are more chaplains to go around.

I spent twelve months in Korea, but I don't recall celebrating any American holiday while I was there. There was work to be done and we kept at it. I had my 22nd birthday over there, but nothing special happened to mark it. It was just another day being a soldier. There were USO shows while I was there, but I did not get to any of them. My company and regiment were for the most part on line or in fighting position.

Sometimes humorous things happened to break the boredom of being in a combat zone. For instance, we had a young black soldier in the company by the name of Farmer. He was from Buffalo, New York. We were in a critical situation one day and Farmer was on guard duty. One of the officers caught him sleeping at his post so they were about to court martial him. They called him before the company officers and accused him of sleeping on duty. He told them that he was not asleep on duty--he just had his eye lids at "parade rest." They dismissed the whole thing. He was a clown. They all had a big laugh over that.

Farmer stands out in my mind because of another stunt, too. This one was not so funny, and it was my fault. I had just made corporal and some of my squad, including Farmer, were in guarding position. It was night and pitch black dark. We were expecting all hell to break loose that night and the words "Red - Bird" were the password and counter password for the night. I eased out to check Farmer and his position. He whispered "Halt" and gave the password "Red." I did not give the counter sign, "Bird." I took another step and he said, "Halt - Red." I stopped and eased up another step or two. He said, "Red" and I stopped, but I did not give the counter sign, "Bird." I did that four times, I think. The last time I heard the c-l-i-c-k of the weapon. I readily spoke or whispered "Bird." I eased up to him and I will never forget his words. He said, "Scarlett, I came close to killing you." I can still hear the click of that M-1 carbine to this day in the corridors of my mind. I still have some IBM recalls. The reason I did what I did that night in Korea was to see if he had any guts. I found out very readily that he did. Out of my own stupidity I came close to being shot and killed. In my 35 years of military service, I never pulled another stunt like that.

Another time, we were going to Wonju (at least, I think it was Wonju) and we were traveling in a 2 1/2 ton military truck. Several of us were in the back of the truck and the top was off of it so we could jump out if we were attacked. While going down this dirt road, we saw a papasan with an ox pulling a loaded cart with some kind of stalks of grain. The ox was pulling slow because the cart was so loaded. Papasan was walking beside the ox. As we passed the ox and cart, our driver backfired the truck engine. The ox went crazy, bucking and pulling the lead rope out of papasan's hand. He bucked and kicked off all that was on the cart. Papasan shook his fist at us and I suppose cursed us. The ox was still bucking and kicking when we drove out of sight. I am sure the ox tore the cart up.

Papasan was not the only Korean that members of our company came in contact with. Korean prostitutes came into the Army areas sometimes. If we were guarding or holding in positions near a village, some of the women made their rounds selling their wares, and some of the soldiers bought their services. Our orders were to leave the women alone. On the front lines, we seldom saw a woman. In the rear area out of harm's way, I saw some American women. They were not prostitutes, however. They were Red Cross workers giving out doughnuts and coffee. We appreciated them.

I spent some time in bunkers in Korea. Inside of them, we had some ammo boxes to sit on and a can of water. Our ammo was close at hand. So were rats, snakes, field mice and weasels. I enjoyed watching them play around the bunker. Some of the weasels were beautiful in colors of cream, red, and mixed shades. One night standing outside of my bunker, there was a big full moon. I was watching a ridgeline for any movement. I kept hearing this "rattle, rattle", so I eased behind a big stump and l listened to that noise for about 30-45 minutes. I couldn't spot anything, but finally I turned my M-1 carbine loose on a brush pile and riddled it good. That stopped the rattle, but I got everybody else out of their positions. I got chewed over that. I could have caused many of us to be killed. The next day I found my enemy. They were two weasels--one cream colored and one red. For all the bullets I fired, I did not kill them.