"By large, Tootsie Rolls were our main diet while fighting our way out of the Reservoir. You can bet there were literally thousands of Tootsie Roll wrappers scattered over North Korea. No doubt it made a nice change from Spam."

- Chosin Few Marine

[This memoir was created from answers to questions asked of Glenn Schroeder in an online interview with Lynnita Sommer (Brown) in 1999/2000. Lynnita put the responses in narrative form, but all quotes and other details and incidents in the narrative are entirely the words of Glenn Schroeder.]

Glenn Burnett Schroeder was born July 12, 1927, on a farm six miles northwest of Dallas, Polk County, Oregon, in a rural area called Salt Creek. He was the only son of Alfred Raymond and Vesta Abigail Zumwalt Schroeder, but was one of three children born to them. His father was a farmer who also worked in a new lumber sawmill for three years during World War II. In 1948, the Schroeders divorced. Vesta, who had been a homemaker until that time, became a waitress.

Glenn Burnett Schroeder was born July 12, 1927, on a farm six miles northwest of Dallas, Polk County, Oregon, in a rural area called Salt Creek. He was the only son of Alfred Raymond and Vesta Abigail Zumwalt Schroeder, but was one of three children born to them. His father was a farmer who also worked in a new lumber sawmill for three years during World War II. In 1948, the Schroeders divorced. Vesta, who had been a homemaker until that time, became a waitress.

Glenn attended the Salt Creek Grade School in Polk County School District #10, which is now consolidated. While in the eighth grade, he worked as the grade school janitor. In his senior year of high school, as part of the National Youth Administration Program, he worked as an after-school janitor cleaning four elementary school classrooms. Besides this work, as was common in farm families, he was expected to work on the farm full time every summer, as well as do his regular chores every day during the school year. Glenn completed his schoolwork at Dallas High School in January 1945, receiving his diploma on 7 June 1945 while in the service.

He grew up in the Depression years and during World War II. "My high school had a Victory Corps," he said. "I was a part of it. We collected all kinds of items, especially tin cans and paper. I usually helped load the material into rail cars for shipment. We had some military drill in PE class. Can you imagine that I always carried my .22 lever action Winchester rifle to school on the bus and carried it to classes? Other guys had larger caliber rifles. My family raised crops on the farm for the war effort. I was the only member of my immediate family to be in the service. Dad was deferred due to occupation and family."

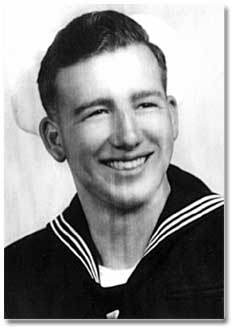

At the time Glenn was about to graduate from high school, eighteen-year-old boys across the nation were being drafted into the military. "I wanted to have a choice and not wait until I was 18 to be drafted," said Schroeder. "We received two Carnegie Credits for enlisting into the service. Those two credits allowed me to graduate from high school." He said he joined the Navy to avoid being a grunt. "I didn't want to crawl around in the mud, but go to sea instead."

He and some other friends joined the Navy at the same time. They included Harry Peters, George Hayward, Robert Friesen, Paul Harms, Robert Rummer, and Glenn. Two joined the Air Corps and two joined the Coast Guard. "I think Harry, Robert and I got the ‘ball rolling' and the others followed," said Glenn. "I think all would have faced the draft immediately after graduation, and decided to have a choice and get a head start on everyone else." He said that his mother wasn't thrilled about her son joining the Navy, but she wanted Glenn to get into a service that had the GI Bill. "Father had to sign the consent. He didn't want to lose a farm hand, but said okay without arguing."

Glenn enlisted and took his physical about 15 January 1945. His call to duty was delayed until the semester was over, about mid-February 1945. He and the others hitched a ride from Dallas, Oregon, to the Navy Recruiting Center in Portland, where they were sworn in. From there they went by train from Portland to San Diego. From the train station, they were herded onto a Navy bus. "We arrived at the main gate, San Diego Naval Training Center, where a bunch of guys who recently finished training, awaited transport out of the place. They yelled at us at the top of their lungs, ‘YOU'LL BE SOOORRRY!' over and over; wonderful introduction!" San Diego Naval Training Station was located on the north side of San Diego Bay. One fence abutted the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, and it was near the airport.

Over fifty years later, Schroeder still remembered his first days at Navy boot camp. "As I recall," he said, "the major event of Day One was to go immediately to uniform issue. We gave our name and service number. Someone made clothing stencils with the information. We moved down a line yelling our chest and waist sizes and had blues and whites, skivvies, socks, etc., thrown at us. We had to use the stencils and paint our name and service number on every item, either in white or black. Our dungarees (chambray) shirts had to be stenciled on the outside of the back." After the stenciling of the clothing, the blue and white trousers were measured for hemming.

"While that happened," said Schroeder, "we packed everything we brought with us, including the clothes we wore, into a box for shipment home. Finally, we had our sea bags packed, rolled into the hammock with the mattress, lashed that stuff properly, hoisted it to the shoulder and were ‘marched' (probably more like rout step) to a barracks. We were split into two platoons, one on the first floor, and one on the second. I was in the second. We were assigned to a bunk, given a ‘head call', and told to fall in outside, where we were lined into four ranks by height. First ‘organized' march was to the barber, where we had our hair cut off. Then we marched to chow. Then it was photo ID card issue."

Schroeder recalled that back in the barracks, the new recruits received instruction on how to make a bunk, roll clothes, and tie the rolls with clothe stops and stow them properly in the sea bag. "The sea bag hung from the front of the bunk along with the ‘ditty bag' that contained personal hygiene items," said Schroeder. After this was taken care of, the men received some basic drill instruction such as "dress right, right and left face, about face, column right, left march," etc. "Then we actually marched around for a while on the grinder," he said. "Other instruction was given such as, here is how you wear your hat; the pockets of your shirts and blouses do NOT exist. NOTHING is put in them. By this time, we were a little dizzy with the entire goings on."

Even after evening chow, the first day of boot camp was not over, Schroeder recalled. "We were instructed on the eleven general orders for sentries, and were told to memorize them from the Blue Jackets manual. Fire watch would be assigned starting NOW! Then we were required to sit down and write a letter to a friend or relative of our choice before lights out."

The company commander or senior drill instructor for the group of recruits that included Glenn Schroeder was Navy Chief Specialist (Athletics) Kiefer. Two seamen second class, who had just finished boot camp themselves, gone on leave, and returned, were assigned to assist Kiefer in the training of the new recruits. One was named Dutton, but Glenn did not remember the name of the other. He did recall that, "all three were real ‘hardnosed' men!"

Boot camp was ten weeks in length. In it, the men learned all the rudiments of seamanship. Major classroom instruction was aircraft and ship identification. The latter was in the dark after night vision was developed. "The ‘hands on' stuff was normally outside and included using the watch talker mikes, compass directions, anti-aircraft gun firing, 5-inch gun firing, fire fighting, gas mask use, rifle qualification, whale boat rowing and operation, physical training, abandon ship (jumping from a 30 foot tower into a pool and using clothing for flotation), naval language and nomenclature, drill, drill, drill, washing clothes and tying wet clothes to a line with clothe stops, drill, drill, drill with rifles. We had to learn semaphore and the eleven general orders for sentries on our own. We were quizzed on those at the most unexpected times."

Schroeder said that his Navy boot camp days were completely regimented, with wake up at 0530. From the moment the DI blew a whistle and flashed the light, it was a full day, he explained. While the whistle was blowing, the fire watch would beat on a stanchion with his Billy club. Then, said Schroeder, it was: "Grab ditty bag and run to the head, wash face, shave, brush teeth, urinate, etc. Make bunk and dress with uniform of day, which was yelled out at wake up. Fall out in platoons for muster, march to chow hall. March back to barracks, sweep and scrub down barracks and heads. Fall out for whatever was on the schedule for the day. After evening chow, scrub clothes on the wash racks, answer questions of DI's, including compass points, general orders, semaphore, etc. Free time came about 2100 for letter writing, tattoo at about 2150, and taps at about 2200 with lights out. Don't get out of the sack except to go to the head." Only on Sunday did things slack off a bit. Most recruits went to church that day. "We marched to chapel," recalled Schroeder, "but the DI did not breathe down our neck at church."

While the company was in the process of getting "shaped up", the drill instructors were very strict. According to Schroeder, if a quarter wouldn't bounce on the mattress cover, the DI would throw the mattress on the deck. He would also throw wet laundry on the deck if there were any "holidays" between articles on the line or the cloth stops were not tied in square knots. He would dump sea bags on the deck if they were not tied properly to the bunk. Corporal punishment was not used to instill discipline in the recruits, but Schroeder qualified his remembrance of this by stating, "It doesn't mean that they did not inflict pain, however."

He said that he remembered the time that he let his rifle butt hit the deck once going to ‘order arms.' "I had to scrub the barracks ladder (stairway) with a tooth brush." The second time he got in trouble, it was because he was chewing a stick of gum in ship recognition class. Chewing gum was prohibited on ships and naval facilities. Even with the lights out in ships recognition class, the DI spotted Schroeder's gum chewing in the dark. He came over to him and said, "Schroeder, put that gum on your nose until I tell you to take it off." Glenn said, "He had me deposit it in a butt bucket after we had all fallen in outside, and gave me a quick lecture about the Navy and the effects of chewing gum on ship decks, etc."

The third reprimand came when the training Executive Officer inspected the barracks on Saturday of week six. "I had not washed the ‘inspection towel' that hung from the bunk. Somehow, the Exec spotted it," said Schroeder. "He pulled it off and said, ‘This man merely refolded this towel to turn the outside in. That is a gig.' "Schroeder further recalled that the men were about to have their first liberty. "I didn't get liberty that day and had to stand fire watch while the rest went on liberty."

Schroeder was not the only new recruit to be on the receiving end of the DI's wrath. He recalled that one guy walked to the barracks alone without waiting to fall in and march with the company. "After evening chow," he said, "he had to take his sea bag to the grinder and run until the DI told him to quit. If he wanted to be alone, he ran alone with his sea bag held over his head. Running with your sea bag over your head was about the major disciplinary action I remember for ‘great' goofs. Another guy had to do that because he had dirt on his shirt one morning. He ran showered, changed clothes and had to wash what he was wearing during the run, all under the watchful eye of a DI. A third one was in the eighth week when a guy couldn't recite general orders. He had to yell them while running with his sea bag over his head."

On occasion, discipline was done on a collective, rather than individual basis, too. Glenn remembered only one time when group punishment was given for an individual wrongdoing. "We were going through various marching drills," he recalled. "One was ‘to the four winds.' One guy got all fouled up and went a different way from his rank. When the company's ranks returned to ‘normal' formation and halted, the DI said, ‘we have a screw up in our midst who can't tell where his wind blows. We will do this at least five more times for each time any one screw up. No one blew it, so we ended drill that day after five more shots of ‘to the four wind.'" Schroeder said that there were no troublemakers within the ranks of the new recruits. "Only five percent or so were draftees," he said, "and those were happy not to be in the Army."

All that marching took energy, which was provided by feeding the troops well. Schroeder pointed out that he was a farm kid, so the quality of the food "took some getting used to." He explained, "Powdered eggs in a huge pan were foreign to me. I had to put catsup on them. I hated lime Jell-O and canned figs!! Other than those three items, it was good food to me."

Between meals, there was a great deal of instruction. The recruits watched documentary and educational films, and Schroeder, like so many other Navy veterans, had a lasting memory of the VD films that showed diseased genitals. "They were enough to scare the heck out of one," he said. For him, the hardest thing about Navy boot camp was memorizing the eleven general orders so that any one of them could be rattled off on demand. And there were unadvertised proficiency tests on a regular basis—identifying compass direction instantaneously, semaphore and phonetic alphabet. Recruits were expected to hit the target with a Springfield rifle and the 1911, .45 caliber pistol. "I didn't pay much attention to that," said Schroeder. "I was reared as a shooter." There was repeated regular marching, quick time, and running from the training center to a large natatorium in La Jolla for swimming tests, abandon ship, water training, etc. "We sang all kinds of songs along the way," said Schroeder. "We didn't use many cadence songs on the base."

He didn't recall any prejudice among the recruits. There were no blacks in any of the boot companies when he was in boot camp. "We had a few Navajo and Pima Indians in our company," he said. "They were not harassed any more or less than any of us." When basic training was over, nearly everyone who had entered the training at the same time as Schroeder was able to attend the graduation ceremony. An exception to this was one draftee who was discharged because his wife had another child, giving him a deferment. "It was also discovered that he was the sole surviving son. His brother had been killed in action about a month prior to his being drafted." Schroeder said that one other man was set back four weeks because he couldn't tell compass degrees instantaneously.

About week eight, he said that the recruits began to realize that they were beginning to be Navy men and that the drill instructors were actually human beings. "We missed winning the ‘outstanding company' pennant for the third week in a row one Saturday," he recalled. "The Chief told us that he was still proud of our performance on the parade ground. We won it twice and could take another shot at it the next week." When Navy boot camp was over, there was no actual "ceremony". Schroeder said, "The senior DI gave us a little pep talk telling us that we learned the basics, were smart enough to learn our jobs once we went to advanced training or to our assigned Naval stations. That was it," recalled Schroeder.

In retrospect, he said that he was in a little better physical shape by the time he got out of boot camp training, even given the fact that farm kids usually do physical labor each day and the fact that he had just finished football season two months prior to boot camp. He said that never during those weeks of training did he ever regret joining the Navy. "I enjoyed the new experience," he said. "At least I didn't have to milk cows." He spent a ten-day leave with his girl friend, family, and friends in Salt Creek and Dallas. With a war on, he was required to wear his uniform on leave, but there was still time to have fun at the beach and meet up with old friends in the small farm community that he called home. After leave, three of the boot camp graduates went back to San Diego Naval Training Center by rail from Salem, Oregon. "At the NTC," he said, "we retrieved our sea bag and hammock and were given transportation to Hospital Corps School in Balboa Park, San Diego."

Glenn Schroeder went to Corps School in May of 1945. San Diego Hospital Corps School was located (within the zoo) on the former site of an international exposition. The barracks was the old Aztec Museum building near the Naval Hospital.

While some recruits ask for assignment to this school upon enlisting, Schroeder did not. He had taken some intelligence tests in boot camp, but during the conference with the Navy ‘job counselor', it was discovered that the Navy felt Schroeder was best suited for signal school. But Glenn was concerned that a physical defect would ultimately end his dismissal from the Navy if it were discovered, so he opted for Hospital Corps. "I was red-green color blind and slipped by the color blind test at the recruiting office," he explained. "I thought I might get bounced out of the Navy if that was ever found out. I told the guy that I didn't want signal school, but wanted the Hospital Corps. He said that he would assign me there if that was what I wanted." Other than high school freshman biology, Glenn had no background experience that qualified him for the Hospital Corps.

Of seven weeks duration, Hospital Corpsman School included classroom studies of "the basic stuff" from first aid-type material to pharmacology. There were also laboratory studies in hematology, analyzing blood and urine samples. In addition, there was nursing training that included bed making, medication, and reading prescription orders. What few lectures the men attended were on basic nursing techniques in hospitals. All of this training was taught by Navy nurses and Chief or 1st Class Pharmacist Mates. With a war going on at the time, Schroeder took his studies seriously. "It was like high school," he said. "I usually studied in the evening before the movie in order to do well."

In 1945, there were no internships. Instead, the Hospital Corps School graduates went directly to duty assignments. Schroeder's assignment was Oakland Naval Hospital in east Oakland. There, he discovered that Hospital Corps School had trained him well for this duty assignment. "When I was assigned to a hospital ward," he said, "I discovered that I could do everything that a ward nurse could do, although I rarely had to do blood counts."

Glenn said that he was a ward corpsman on a "dirty surgery ward." He said, "Most patients were Marines with belly wounds, many with spinal injuries which paralyzed them below the injury. We had 12-hour shifts and were subject to four-hour ‘special watch' duty at night for patients who needed around the clock help." After promotion to HA 1/c, he was changed to night duty on a clean surgery ward and had no special watch duty. "In both instances," he said, "I did everything from back rubs, administering enemas, medication by hypodermics, serving food, taking temps, cleaning and autoclaving syringes, needles and instruments. We did anything and everything that related to care of hospital patients."

When his accumulated leave expired, Glenn Schroeder was discharged from active duty in the Navy on October 30, 1946. He then joined the inactive reserves, but can't explain why he did such a thing. "I do not know what possessed me," he said. "I guess the discharge people assigned the best salesman to talk to those being processed for discharge. It sounded great! One would accumulate time in grade and for pay purposes if, at any time in the future, I was subject to being drafted back into the service or wanted to re-enlist. It sounded like a winner." While in the inactive reserves, he was not required to attend meetings or take further training.

In addition to joining the inactive reserves, Schroeder went back to high school as a post graduate for half days, taking chemistry, Latin, and algebra for preparation to go to Oregon State University's pharmacy school. He worked on his dad's farm the remainder of the time. When he discovered that OSU required freshmen to live in a dormitory, he told them "No way!"

About that time, a high school friend saw him on the street and inquired what he was doing. "I told him that I was looking for a job," Schroeder said. "He talked me into going to Oregon College in Monmouth to play football. I would not have to live in a dormitory. There was a room open in the house where he and some other guys I knew were staying in Monmouth. So, I went to college until I was recalled into the service." He said that he was on a "fast track" that enabled him to attend summer session to pick up some credits. "The football coach always managed to find a job for me on campus," he recalled. "I was in my last summer session and working when the war broke out."

About that time, a high school friend saw him on the street and inquired what he was doing. "I told him that I was looking for a job," Schroeder said. "He talked me into going to Oregon College in Monmouth to play football. I would not have to live in a dormitory. There was a room open in the house where he and some other guys I knew were staying in Monmouth. So, I went to college until I was recalled into the service." He said that he was on a "fast track" that enabled him to attend summer session to pick up some credits. "The football coach always managed to find a job for me on campus," he recalled. "I was in my last summer session and working when the war broke out."

Schroeder said that the outbreak of war made him a little nervous, but his four-year hitch in the inactive reserve was up on 30 October 1950, so he didn't pay too much attention. He just studied and worked. "However, President Truman suddenly extended all enlistments by one year," he said. "That got my attention. None of my friends who were in the active reserve were being bothered, so I didn't break out into a sweat. Naturally, I thought that they would be called to active duty before any of us in the inactive reserve. That myth was exposed on or about 5 August 1950 when I received a big manila envelope from the 13th Naval Distribution Headquarters in Seattle." His father had forwarded the envelope to him from home. Inside was the message, "Congratulations, you will report for active duty to Sandpoint Naval Air Station no later than 1 September 1950." Schroeder said the delay to report enabled him to finish summer session, leaving him with just two more quarters (including student teaching) to graduate from college.

In practical terms, he said that he had only about twenty days to get organized for active duty. "I needed a graduation check and my car worked on so my girlfriend could use it to commute from Dallas to Monmouth (10 miles) to attend college," he said. "I went to the registrar's office, explained what was happening, and asked for a graduation check to find out exactly what work, other than student teaching, I needed to graduate. I took my 1934 Chevy to my uncle's Pontiac dealership in Dallas for a ‘look see' about what it needed to keep it on the road for another year. Fortunately, it didn't need very much work. I went over my graduation check with the Registrar, and found that I could easily finish the curriculum in two quarters."

Unlike many other reservist corpsmen, Schroeder was not sent to Combat Corpsman School immediately upon recall. He had to report to Pier 91 in Seattle. "No one could find my records for about a week," he recalled, "so I ran around there in civvies. I was put to work in the medical unit giving inoculations to new inductees. Those guys were skeptical of a guy wearing a letterman sweater giving shots!" But, the records finally got squared away and Schroeder was issued a sea bag of uniforms. He was then sent to Tongue Point Naval Station in Astoria, Oregon, where he was in charge of the outpatient clinic office. "I bitched a little that the job called for more rank than an HA 1/c—I should be jumped to a Pharmacist Mate 2/c at least! In my dreams! At least I could hitch a ride to Dallas every weekend with a guy from Eugene, Oregon."

At Tongue Point, Schroeder was quite independent. "I was in charge of the outpatient office and did everything from keeping the files, requesting files, handling the patient traffic, testing the urine of the pregnant dependent wives, etc. I did all of this without supervision as long as the doctors were happy with my handling of the patients."

He said that Tongue Point became overrun with corpsmen. "All of the inactive corpsmen were being recalled," he said. "On or about 20 December 1950, a number of us received orders to other stations. The guy from Eugene was assigned to a cruiser. Two of us were assigned to Combat Corpsman School at Camp Pendleton. That shook us up a little because 99 percent of the Navy casualties in ‘Our Navy' every month were corpsmen with the Marine Corps."

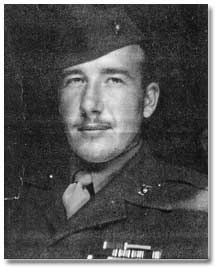

Combat Corpsman School also carried the name "Field Medical Training." It consisted of two very different segments: the medical aspect of being a combat corpsman, followed by fifteen days of infantry training with Marines. Schroeder took this training at Camp Pendleton from 6 January 1951 until 17 February 1951. Upon arrival at Camp Pendleton, he was issued a sea bag of Marine uniforms, and his sea bag of Navy uniforms was shipped home. He was also issued a standard medical kit which contained a surgical kit with scalpel and scalpel blades, suture needles and sutures, hemostats, probe, bandage/clothe scissors, tweezers, etc. Along with that, they had field compress bandages, surgical tape, sulfa powder packets, morphine curettes, APCs, aspirin, disinfectant, and water purification tablets. "Actually," he said, "we weren't ‘required' to have certain items. We would eliminate what was not essential and add what was, based on experience. I'd leave some of the stuff in my field pack in a jeep or a truck, and load up on stuff more appropriate for the mission we were on at the time—e.g., clearing or planting a mine field or engaging in a fire fight with the enemy."

Once they received the necessary gear, he and other trainees were bussed to Camp Del Mar on the beach side of Camp Pendleton. There, their assigned living quarters were two-story, wooden barracks that Schroeder considered "modern" for 1951. There were about thirty guys on a floor. The classrooms were built about the same, but they were only one-story. "There was a PX, movie-theater, and a dispensary where we received our shots," Schroeder said. "The camp was on the beach, which we used for assault training. It also had enough room for a little drill, and places for non-firearms weapons training. It was part of Camp Pendleton, but on the beach, to the west of Highway US 101 in Oceanside, California."

Reveille was at 0530, recalled Schroeder, "this gave us time to learn the uniform of the day, take care of personal hygiene, make the bunk and bounce a quarter on it, and go to breakfast. As I recall, we started our daily training at 0700 and ended about 1630." For this training, they were issued M1-A carbines, bayonets, and complete combat web gear. "We had everything a Marine would have," explained Schroeder, "including shelter half, blanket, pegs, web belt with mess kit, coffee cup, and canteen, compass, two-part field pack—in which we had a change of clothes that included two pair of socks, tee shirts, and shorts. The medical kit was standard. "We were supposed to learn field medicine," Schroeder said. That consisted of giving immediate attention to all kinds of combat-induced trauma to various parts of the body. "Quick attention is essential in saving the lives of wounded combatants," he explained. "The ‘what to do' and ‘what NOT to do' for each kind of wound was taught."

On weekends, there was usually some time out from the training to go on liberty, but Schroeder didn't go on liberty very often during the original corpsman school training. "$21 per two weeks didn't go very far," he explained. "I did go on liberty more in Combat Corpsman School. I went to Hollywood to visit my girlfriend's two aunts." He also went out with some Navy guys from time to time. "Some Marines would do double takes at a guy wearing a Marine uniform with Navy blue rank and hash marks on his sleeve! That was fun," he recalled.

What wasn't fun was cold weather training. After Chosin, this type of training became an integral part of the instruction given to Marines and Navy corpsman about to be assigned to Korea. Schroeder and other trainees went by bus and trucks to a place called Big Bear, somewhere northeast of Camp Pendleton. "We set up a camp and established a perimeter," he said. "The company was supposed to attack and attempt to capture an opposing force's camp. We had a few tents set up for night. I was in an aid tent that was ‘knocked out' by infiltrators some time during the night. I was informed at morning chow that I shouldn't be eating—I was dead! The lesson was that officers and corpsmen are the first primary targets!" He said the exercise lasted two days.

According to Schroeder, infantry training overall consisted of learning some basic combat skills such as throwing grenades, assaulting a beach, finding and taking cover, the use of the M1-A carbine and bayonet. They had perhaps just one short session on the use of hand grenades. "We learned how to throw grenades," he said. "I found that to be fun. I put several simulated grenades through the ‘window' target. The Marine instructor told me that I was a natural Marine and in the wrong outfit!" The trainees also were taught close combat training with the bayonet. The remainder of the training was infantry training where trainees spent time "taking" a small village. A sort of final exercise was climbing down a cargo net into a Higgins boat, assaulting a beach, and then encountering Marines with various wounds. e.g., a sucking chest wound. We had to take care of the wound, fill out a tag indicating what we had done for the person, and the time of administering any medication, such as morphine."

Trainees did not work with any Marines in Combat Corpsman School except for combat skills instructors. It was only during the final fifteen days of Marine Infantry Training that Schroeder was teamed up with Marines. "After the second day," he recalled, "I said to me, ‘Hey, these guys are great!' They could all tell what I was because I had my field medical bag, as well as all of the Marine gear, including the M1-A carbine. The carbine gave it away also. The Marines had M-1 rifles." When the training was over, the corpsmen marched in review and were then ready to ship out to Korea.

Schroeder did not have the opportunity to return to his home in Oregon prior to shipping out. Like all corpsmen (and unlike the Marines), he was required to sight in his M1-A carbine, and then pack it in grease for loading into wooden cases for shipment to Korea in the hold of the vessel. "We couldn't march down the main street of San Diego bearing arms," he explained. "That was against the Geneva Convention. However, the North Koreans were shooting corpsmen, so we could be armed. We just had to make it look good for the newsreels in the States. What a crock! If I knew then what I know now, I'd probably have insisted that I carry my firearm with the Marines!"

He further explained that, traditionally, replacement battalions heading for Korea were taken to San Diego in a fleet of busses. "We exited the busses about a mile from the dock and marched, by company, down the street singing cadence," remembered Schroeder. "Guess it was some kind of ‘Hey, look at us. We are off to fight!' He said that the Geneva Convention had a provision for corpsmen to carry firearms when facing an enemy who was not a part of the Convention, or was ruled as not abiding by it. "We were given some crap about how the corpsmen shouldn't carry weapons in public because someone might see that and raise objections under the Geneva Convention," he said. "In retrospect, we all looked alike. The only difference between the Marines and me was my medical kit, which was difficult to spot when marching en masse. Besides, I had to pack my carbine in gun grease, put it with others in a crate, and clean it in Korea—A waste of time!"

On or about 12 March 1951, Glenn Schroeder boarded the USS Aiken Victory, bound for Korea. "It was a World War II cargo ship partially converted to a troop transport," he said. "I think it could carry about 600 men in the center holds. The only men on board were Marines, and Navy corpsmen and doctors. The crew was Navy and civilian employees of the Navy. There was cargo in the forward and aft hold. The troop holds had multiple rows of racks seven high, about 36 inches wide, and 24 inches between racks. One had to climb to get to the upper racks. The guys on the bottom were vomited upon by the seasick people above."

During his stint in the Navy at the tail end of World War II, Schroeder was a "landlocked" sailor. This was his first time on a large ship. "I became sea sick in San Diego Bay as soon as we pulled away from the dock," he recalled, "and I was sick all the way to Japanese waters. There were quite a few sick people. One tried not to get downwind of anyone, just in case! There was vomiting in the holds, which would set off a lot of people!" He said that the ship took the Great Circle route on its journey to Korea. "We hit some very bad weather near the Aleutian Islands. The Pacific was breaking over bow with fore to aft waves. Also, we had side waves that would put us into troughs. The ship was heaving in both directions, sometimes both at once."

While the ship was heaving, so were its passengers, including Schroeder. He was too sick to worry about entertainment, and too sick to carry out any assigned duties. "I was too sick to worry about anything other than not throwing up," he recalled. Entertainment consisted of "watching the ocean while trying to get some fresh air. When we got closer to Japan, we watched flying fish and phosphorescent flashes of the water." During the trip, he was too sick to make many new friends, and mostly knew only some of the Marines who had been in his company for infantry training. Although he doesn't remember names, he said that one Marine stood out in his mind. "I do remember a very funny guy from Muleshoe, Texas," Schroeder said. "He always used strange nomenclature for his equipment—e.g., cartridge belt was his bullet belt; field pack was a buffalo hump; his M-1 rifle was his 8-shooter; canteen was a water bottle." The 12-13 day trip was broken with a short six-hour stopover in Kobe, Japan. "We were instructed that we could take no more gear than we could carry in our field packs," recalled Schroeder. "Kobe was where we took our sea bags to a warehouse for storage." From there, the ship sailed on to Pusan, South Korea, where the Marines and corpsmen would soon disembark. The date was on or about the morning of 26 March 1951.

Upon arriving in Korea, there was an hour's delay to disembark. "Personnel people came aboard to give out individual assignments," Schroeder explained. "Just because we were organized as companies, didn't mean that we would all stay together. A couple of guys worked with the corpsmen. As soon as we were given our assignments, we each picked up our gear, went to the gangway, saluted the OD, asked for permission to leave the ship, saluted the colors, and went to the dock." Schroeder said that it didn't seem like a foreign country when he first stepped onto the shore. "The only people I could see were U.S. military. There was an Army band playing on the dock, which made me wonder about where in the heck we were docked. Red Cross ladies were SELLING coffee and donuts! However, all of the Marines I dealt with at the port were armed. That was the only clue I had that we could be in a war zone."

According to Schroeder, the chief medical officer was not happy that so many seasick corpsmen had spent so much time in their racks on the ship. "The chief medical officer on the ship told us sea sick corpsmen that he would try to get us assigned to the worst possible duty for being on our racks most of the time to keep from throwing up. About an hour after arrival, I received my assignment: Charlie Company, 1st Engineer Battalion, 1st Marine Division. That was as specific as it got. The 1st Engineer Battalion was the only Marine combat engineer unit in Korea. It supported the entire First Marine Division."

After retrieving his weapon and cleaning the Cosmo line out of it, Schroeder went to the transportation people. "Some of us were loaded on a bus and taken to the airstrip," he said. "We climbed aboard a DC-3 (the one with the tail wheel, two engines and sling seat along each side of the plane), and flew to another airstrip just north of Taegu. It was my first, multi-engine flight." After landing in Taegu, the men were trucked north to a replacement camp of some sort, where they drew cold weather gear and had a hot meal. Schroeder remembered that it tasted great after being sea sick for so long. "We received a three-minute class in combat survival (what they don't teach you in school)." Lesson One: The sleeping bag had a ‘panic' zipper. If pulled clear up, the bag would fall open. Lesson Two: Sleep in your clothes and field boots. Lesson Three: Sleep with your weapon loaded on safe. Lesson Four: Sleep with your K-bar or bayonet for a close kill. "That Marine really got my attention," said Schroeder.

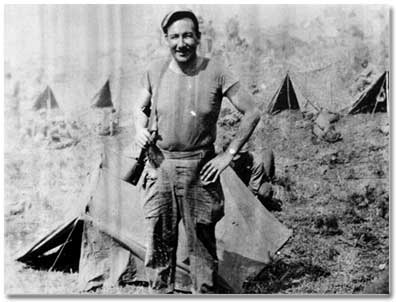

The next morning, a supply truck took Schroeder, a couple of Marines, and some supplies north to Charlie Company, 1st Engineer Battalion. The company was located just south of Hongchon, off line for a short respite. The Army's Second Division was on line at the moment. Here and there, Schroeder saw Korean natives for the first time. They were at farmhouses and in a small village on the road to the replacement camp and to the company.

"The company had only one corpsman on the roster when I showed up," recalled Schroeder. "It was still one short after I arrived. The only corpsman and I split the workload. I would have the third platoon; he had the first platoon; and we'd both rotate on the second platoon until we received a third corpsman. I would be responsible for seeing that each man on the company roster received a chloroquine tablet each week." He said that getting the men to take the table wasn't too difficult of a task. "Contracting malaria was a court martial offense," he said. As part of getting squared away on ‘what was where' so he could get his job done, he drew ammunition and two 30-round magazines, along with some hand grenades. Three days later, his company took intense artillery and mortar fire. For the first time in his military career, Glenn Schroeder found himself well and truly in a combat zone.

During his first few days with the company, the Marines to which he had been assigned were leading infantry support tanks on a road, finding and pulling up mines. "I tried to watch for snipers in the brush and trees. We missed seeing a mine indentation, which was not picked up by the minesweeper because the only metal in a tank mine was the blasting cap. It blew the track off of a tank."

It was probably two weeks after he arrived in Korea that Schroeder saw the first dead enemy on a hillside. "I thought that was one less I'd have to worry about," he said. "I never did look into the face of a dead Marine. The dead Marines I saw were covered at Battalion Aid station. All I can say is that I was sorrowful, but glad that it wasn't me or one of my platoon." He also said that he was happy about not being assigned to an infantry company, where casualties were often very heavy. He learned early on not to get too friendly to any of the men in his platoon. "It was too risky," he said. Casualties came far too easily in the Korean War, and it was very hard to deal with the death of a close buddy.

As for how he was holding up emotionally being new on the front line and in a war, Schroeder recalled that, "I was okay, but scared to death! I certainly developed all of my sensory perceptions very quickly. My power of observation increased beyond my belief. I think I could see an ant move in the brush or a mine indentation or trip wire from twenty yards! If one isn't afraid when people are hurling artillery, mortars, or small arms fire at one, one is an idiot and in need of great help!" He carried an M1-A automatic/semi-automatic (selector switch) carbine with two, 30-round magazines taped together for a quick reload. "I tried a Thompson submachine gun," he said, "but didn't like it after I fired it. Other than the M1-A, I had a bayonet and a K-bar."

The company skipper was Captain Harmon, and his platoon leader was 1st Lieutenant Brown. "They were always in front of us, regardless of what we were doing," he recalled. "If we were clearing or planting a mine field, they were right there in the midst of what we were doing. Sometimes I thought they were a little nuts, but they never asked any of us to do what they would not do. They always called me ‘Doc'." They and other "old-timers" in the platoon made certain that the newly-arrived Doc Schroeder always had his weapon with him and kept his eyes moving to look for people in the brush and mine trip wires.

Schroeder explained that the firing of the enemy let up only when they felt like it, so the old salts in the platoon also taught him how to find cover very fast. In addition, they reminded him to carry lots of ammo and hand grenades, and they told him to stay as far away from tanks and other vehicles (which were favorite targets of the enemy) as possible. "We usually escorted tanks to find mines," he said. "Those beasts drew enemy fire like rotten meat draws flies. Sometimes tanks were used as close artillery fire, especially at night. That would bounce one off the ground," Schroeder recalled. Once a Brigadier General came to the front where the company was pulling a minefield. Unfortunately, the top official did not come alone. A tank escorted him. "That pissed us off," said Schroeder, "because tank drew so much fire."

On his first night in Korea, he had been taught to keep his clothes on while in his sleeping bag. It didn't take long for him to discover that Korea was VERY cold at night, so he found an extra jacket and practiced that first rule of thumb always. During March, April and May, Schroeder said that things were frozen in the morning because of the cold nights. Days were above freezing. "The valleys were several miles wide," he said, "but got narrower as we moved north. The hills got higher and steeper as we moved north. I suspect some ‘flatlanders' from the Midwest would call them mountains. There was brush and trees on the hillsides which could hide the enemy, as well as serving for our cover when needed. We usually used foxholes. I saw slit trenches only on the crest of hills when it was the MLR. I never did see a bunker."

He said, "We spent a lot of time ‘in front of the front', because the job of the Marine engineers to whom he had been assigned was to clear roads and sides of roads of mines the enemy had planted. "We needed to clear them to keep the tanks and infantry from running into them as they moved forward," he explained. It was not uncommon for his platoon to receive artillery and mortar barrages while this mine extrication was taking place. "We were quite mobile because we were supporting the entire 1st Battalion, 1st Regiment," he said. "We had to go do whatever was needed to be done for any and all companies in the battalion. For example, Able Company might say, ‘We can't move until this minefield is pulled!' Or Dog company might say, ‘We are staying on this ridge for the day, so we need some mines planted and a little concertina wire strung.'" During Schroeder's stint in Korea, these various jobs took his platoon to Hongchon, Chunchon, Hwachon Reservoir, Yanggu, and the Punchbowl area.

When he arrived in the warring country, his platoon was near Hongchon, and then they pushed north through Chunchon. "The Captain wanted to see the dam that made the Hwachon Reservoir, in case we had to destroy it," he recalled. "I went with him in his jeep, along with two sergeants. Talk about getting shelled/mortared for being in front of the line!! We drew back to Hongchon. Some guys from my platoon set booby traps in Chunchon before we walked toward Hongchon. We dug in with the 1st Battalion, 1st Regiment. I met a friend from Oregon who was with the grunt Marines. And I darn near froze to death that night with no sleeping bag and only a tanker jacket."

According to Schroeder, it was here that he saw his first natives "up close" when the platoon came to a house where a mother and daughter were living. "They would not leave," he said. "Each wore a traditional VERY short blouse which allowed their breasts to be exposed. The elder woman had breasts that hung down. I told a guy who was planting a booby trap that if I made it out of Korea, I'd come back here as a bra salesman after the shooting was over. The guy asked me not to make him laugh while he was handling explosives!"

The platoon then moved to the Yanggu/Punchbowl area. There was no difference between that area and that around Hongchon, except that the terrain was steeper and the valleys were narrower. "Not much unusual happened there," said Schroeder. "It was routine war—sweep mines for tanks, put in mine fields in front of the lines, pull out mine fields in front of the lines, dodge artillery/mortar fire, stare down at the Chinks and listen to them blow bugles and blare propaganda over PA systems. We made sure to keep our heads down from small arms fire, etc." He also said that his platoon was careful about "staking out" the area to prevent the enemy from sneaking up on them. On occasion, foreign troops other than Americans were in the area. He recalled that some British troops bivouacked next to his platoon one night.

"The ROK army was horrible," he recalled, but he said the Korean Marines were good fighters. "We usually had to fill a gap when the ROK army bugged out," he said. "The KMCs rarely lost a position." Schroeder referred to the ROK army as a "paper army." He explained this reference by stating of the ROK army, "Every time it took over for a Marine unit, it would ‘fold up and run' when attacked. They would come straggling down the road with masses of brush in their helmet webbing. Why was I pissed off? Because we usually had to go support the Marines who had to plug the gap left open by the ROKs. It didn't take long for me to understand clearly that their ‘bugging out' put our lives in jeopardy when it was THEIR country! If they didn't want to die for it, why should I?"

As for the enemy that his platoon and all of the United Nations forces were dealing with, Schroeder said they seemed to have about the same age spans as our own guys. "The Chinks were good fighters, but very suicidal," he recalled. "How long has it been since US forces ever made mass frontal assaults blowing bugles?" The enemy carried Russian 7.2 mm bolt-action rifles and carbines, and each could hold five rounds, said Schroeder. "Some were armed with ‘burp guns' that could fire about 700 rounds per minute, if one could load it that fast. "The rifles and carbines were quite accurate," he said. "I suspect the burp gun was effective if it was sprayed around."

Schroeder recalled one incident when his company was clearing anti-vehicle mines from a road while chasing the enemy north. "We always scouted both sides of a road for any enemy who might be spotters, snipers, etc.," he explained. "I took the woods on the right side of the road with the staff sergeant who was in charge of the cook trailer and rations. We found a dead South Korean soldier who had compound fractures of the left leg and arm. I lifted two brass spoons from his jacket pocket, his ID card, and an epaulet. We scanned all of the trees for enemy ‘in the tree tops' and the ground for any ‘unusual' items. I spotted a brush pile that looked manmade. We each took one side, looked for mine wires, and lifted the brush with our rifles to fire immediately, if necessary. There was a dead North Korean soldier under the pile. He was wearing a drab set of coveralls. I ripped the front of the coveralls with my K-bar. The dude was wearing a dress uniform. I took his ID book from his top pocket and epaulets. His mouth was open and he had five gold upper front teeth. The staff sergeant said that if I'd pull the teeth, he'd give me a Japanese police sword he'd picked up somewhere. I pulled the teeth, which were easily extracted because they were in one piece, and gave them to him. I still have the guy's ID book, spoons, epaulet, and the Japanese sword."

Charlie Company engineers received all kinds of fire support as they dealt with the enemy and performed their mine-related duties. Included in this support was fire from 105 to 8 inch artillery, including mortars up to 4.2. "We had air support when called for," he said. "Jets were okay for hill top napalm drops, but the F4U Corsairs were best for a narrow, winding valley."

No matter what kind of firepower was there to try to protect the Marines and their corpsmen, casualties were inevitable. Doc Schroeder himself was injured on 3 July 1951, as they were working their way through a narrow valley checking for anti-vehicle mines. "The Chinks had that place zeroed in with mortars," explained Schroeder. "One tried to put a mortar round into my pocket. Fortunately, I was merely hit with a passing piece of shrapnel." The wound was enough to earn the Navy corpsman a Purple Heart.

Schroeder said that one of the Marines in the company must have had a ‘death wish' that day, because he wore a white tee shirt that could be seen for miles. "I told the sergeant, ‘That SOB nut is going to bring in all kinds of mortar and artillery fire on us and attract every sniper within a thousand meters. Before the sergeant could say anything, both of us could hear the mortars fire and the ‘whooshing' began, followed by the explosions. The cook sat down by a tree and began to sob hysterically. One guy wanted me to shoot the guy because he shouldn't be a Marine. I sat down, got his attention, and told him to shape up and help us by taking some cover instead of hindering us in dealing with the situation. The guy with the death wish didn't get hit, but I did—which ticked me off. The young cook never cracked again while I was there. I didn't keep track of the nut case with the white tee shirt. I think the sergeant may have lifted it as not being a regulation tee shirt."

Glenn's wound was not a serious one, but other platoon members were not as lucky as Schroeder. The former corpsman said that while he was in Korea, he patched up about a dozen guys, all from artillery or mortar fire. "We rarely received much small arms fire except for putting in/pulling out mines in front of the line." Some casualties could have been avoided. "One such event qualifies in my mind," Said Schroeder. "The Captain and a guy took cover in an indentation dug into the side of the road. The infantry was trying to take the hill. The Chinks had carried an old 75mm pack howitzer to the top of the hill and were firing it down the hill. The Captain was ‘eyeballing' the hill with binoculars. Waving binoculars around is not the thing to do. He handed them to the other guy who lifted them to his eyes just as a 75mm round went off right in front of them. A big piece hit the guy right in the mouth. The Captain was not injured except for a little ringing in his ears. I had to take care of the guy and get him about 400 yards to Battalion Aid. I was pissed, mumbling something about them having no business trying to be spectators when there were more mines to pull—just look at the tanks with tracks blown off!"

As for other "spectators", there were non-military personnel attached to the platoon, recalled Schroeder. "We had an interpreter. Once in a while we had laborers who would carry Concertina wire up hills." Those laborers often carried supplies on their backs with an "A-frame. "We were amazed at the huge loads they could carry," Schroeder said. He said that there were times when the men in his company might have fired on civilians who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. "I know that I shot at some people who might have been civilians, but one can get dead in a hurry if one doesn't act first and ask questions later."

Besides the Marines and their supporting personnel, Schroeder's platoon came in contact with the US Army's Second Infantry Division. "They were not much better than the ROK army," he complained. "The Second Division, in our estimation, were doing as little as possible. Any time we went past a Second Division unit, we would yell, ‘Second to None (which was their motto), and First to Run!' It seemed that every time the Second Division took over the line to relieve the Marines, they would be sent into retreat and the Marines would have to go back to stuff the holes."

While Schroeder had his fair share of complaints about the Second Division, he said there was one thing that the division was good for in his estimation. "Another corpsman and I," he said, "along with a jeep driver, would find one of their MASH units. While one corpsman begged for some supplies, the one who wasn't begging would load a few five gallon cans of 190 alcohol into the jeep while the driver was over at the mess supplies, stealing cans of grapefruit juice. It was a ‘no sweat' operation, and, yes, we shared the 190 with all of our guys."

During the entire time he was in Korea, Schroeder always worked with his guys—the Marines. He was never assigned to an aid station, where supplies were generally more abundant than in the field. He said, "I didn't run into a problem I couldn't deal with and get a man shipped off to better care when needed. I never did need something that I didn't have." But he admitted that he had one persistent worry. "I was always afraid that I might need to make a tracheotomy and didn't really know how to do that, nor did I have a tube. I could have cut in with the scalpel," he said. Fortunately, he was never called upon to perform that dangerous procedure.

Schroeder, however, was called upon to do something else dangerous, and that was to accompany the Marines when they were clearing anti-personnel mines. He said the men found an armored vest in one of the trucks they were riding in to get to one of the minefields. "I have no idea where it came from," he said. "It was probably stolen from the Army. No one wanted to wear it, even when clearing antipersonnel mines or when under fire. It was rattling around on the truck. A guy said, ‘You put this on, Doc. I might need you to save me.' Very prophetic!" Schroeder said that it came in handy when a 75mm gun opened up on them at the bottom of the hill. "I sat on the darn thing until we bailed out at the bottom of the hill. The guy who said that to me was the one who was hit in the mouth by shrapnel from that 75mm gun. Any time we moved by vehicle, I found that vest and sat on it!!" Schroeder said that, "the hardest part of a corpsman's job in general in Korea with an infantry company was staying alive to help others who were wounded."

As for him personally, he said, "The hardest part of my job was keeping track of my weapon when we were under fire and someone was hit. I kept losing the darn thing, but always found it after firing let up." As for holding up as one of the company corpsmen whom the Marines counted on to keep them alive under adverse conditions, Schroeder said, "I think the saving grace was that everyone, including the seasoned combat veterans, were scared spit-less. I think we put up a good ‘front', but the experience eventually ‘got to us' much later."

According to Schroeder, "I didn't ‘flip out' until the Gulf War, when I heard that one of the first casualties was a corpsman with the Marine Corps. That brought everything back and crashed on me. Guess this isn't an ‘average' man's experience, but I think that playing collegiate football—a tough sport—helped me deal with the situation." From personal experience in a war zone himself, Schroeder knew the general dangers that faced that corpsman in the Gulf War.

A veteran's concept of what does or doesn't make a "hero" varies, depending on the veteran. To Glenn Schroeder, a "hero" was someone who did very risky things ‘above and beyond anyone's expectations.' And, he said, "someone who does those things without thinking about it until later—then wonders what made him do something so silly." In his company, he said there was no such individual during the time he was in Korea. However, prior to his arrival in Korea, one of Schroeder's fellow corpsman—one who had landed at Inchon with the company--was awarded a Bronze Star for carrying out his duty under fire.

Life in a combat zone was full of challenges, and not the least of these were the not-so-simple challenges of keeping oneself personally clean, and trying to find some decent chow to eat. Schroeder said there was no set schedule for the former. "If we happened to pass a shower unit, we would strip off dirty clothes, look through piles of clean clothes for replacements, get into the cold shower, lather a little soap, try to get dry, and put on clean clothes. We shaved when we had an opportunity."

As for food, he dreamed of grilled steak and an ice cream cone, but settled for C-rations instead. "We had a portable field kitchen," he said, "but the food was terrible, except for Spam. There were dehydrated potatoes, beef and gravy, fruit cocktail, dried milk, powdered eggs, and individual boxes of cereal." The food in the portable field kitchen was so distasteful to Schroeder, he said he preferred the C-rations, which he really liked—especially the beans and franks and lima beans and ham. He said he never had the opportunity to eat the native food, because there were few civilians near the places where the 1st Engineers were camped. "The Korean Marines ate rice balls with a piece of dry fish in the rice ball," he recalled. "No wonder they fought well. They were angry!"

Of course, Schroeder said this with a sense of humor. But he said that as far as he was concerned, trying to survive a war was actually very deadly, serious business. He recalled one instance when the platoon came under intense mortar fire, and he insisted that the sergeant get inside a culvert with him. "Moments later," he said, "a round went off near where we had been in the open. This same sergeant later told Schroeder that he was getting a day off to go to Masan to re-enlist. "I told him that I was going to get him a psych discharge for doing that," exclaimed Schroeder.

Lighter moments were few and far between, so much so that Schroeder remembered only one such moment. "We were in front of the lines pulling a mine field," he said. "About fifteen enemy rustled out of the brush with their hands up. We certainly drew down on them. A couple of us started to laugh because these were all little Chinese (maybe about 5'6"), except for one guy who was about 6'3" or taller. I said, ‘Our basketball coach back home would like this guy!'" A bunch of Marines laughed, breaking the tension of the moment.

Also breaking tensions was mail from home. Schroeder received packages from his girlfriend and parents, and the mail was coming regularly about once a week or so. He recalled that he once asked for his girlfriend to send him an Oregon state flag so he could put it on his shelter-half or a tent. Another way of breaking the tension associated with always being on the alert to the dangers of war was to have some religious guidance. "It would have been nice to have had a church service once in a while," said Schroeder. "But I never saw a chaplain once we left the ship. I have no clue as to where they were hiding."

Schroeder said he also never saw a USO show, never celebrated the day he turned 24, and never celebrated Memorial Day, Fourth of July, or Labor Day while he was in Korea. He also never went on R&R. Entertainment was simple and basic: "We had a little 190 alcohol, and once in a while we'd get a ration of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer, courtesy of Augie Pabst. I smoked and the smokes came in the C-rations." The nicotine in the government-issued cigarettes helped calm frayed nerves as the Marines and corpsmen of the 1st Engineers faced the hazards and uncertainties of war.

"I think that the most disconcerting thing in Korea was the Chinese psychological warfare," said Schroeder. "We'd climb hills with the infantry, kick the Chinese off the ridge line, and dig in. Our job was to string concertina wire, plant anti-personnel mines, and tie some C-ration cans with rocks in them to the wire. All the time we'd be doing this, some Chink would crank up a PA system and start screaming over it, ‘You Marines will die if you don't go home. Truman is sleeping with your wives and girlfriends.' Etc., etc. Or, ‘We will attack you when the bugles blow.' In a few minutes, some bugles would blow. We'd jump into foxholes and aim rifles and BARs down the hill. There would always be some enemy moving around down the hill, but normally out of range. Or, bugles would blow and we'd hear some mortars fire. I guess it was just another day at war, but it always put one's teeth on edge because we'd know that we were being watched."

Schroeder said that he always felt that he was in extreme personal danger while he was in Korea. "I guess it wasn't the time I was wounded that I felt I was in the most personal danger. Instead, it was the time we were pulling a minefield that had killed a cow. We were about a kilometer in front of our lines. The Captain had me and three Marines take a stretcher to a house where the cow's owners were supposedly ‘holed up.' The word was that a guy and his wife were in that hut. We had no clue as to where the enemy was located, although we were drawing no fire. The four of us went up to the house. One Marine peeked in a window and motioned that he could see two people, one on the floor. We crawled around to the door, one guy kicked it in, and a second ran in with his rifle at ready. We all had grenades at the ready. The man and his wife were in there. The guy had taken some of the mine in the belly. Both he and his wife were drunk. I put some sulfa powder and a field compress on the guy, and gave him a big shot of morphine and tagged him. We loaded him on the stretcher, grabbed his wife, and took off back to where we started. We then loaded them on the Captain's jeep and off they went to the rear. We had to ‘cold camp' there overnight. When we finished the next day and left to the rear, it was a great relief!"

There were many veterans who were also relieved to know that peace talks were going on elsewhere in Korea. But Schroeder was skeptical. "I told everyone that the peace talks in the summer of 1951 were nothing more than an opportunity for the enemy to get regrouped, and we should ‘pour it on.' I was discouraged because that did not happen, and because I was correct." The war continued on until there was a ceasefire in July of 1953. Schroeder's personal war in Korea, however, ended on 10 September 1951, when he left the country to return to the States.

Schroeder said that he got word that the 1st Sergeant had asked for him. "I reported to him and he said that he had orders from battalion headquarters to have me ready to leave for the States in two days. I found some reasonably decent clothes, packed what I wanted into my field pack, dumped what I didn't want (my shelter half, etc.), and just said goodbye to anyone I saw. As dumb as it sounds, I was both a little glad and a little sad to be leaving. I felt for the guys who were there when I joined the outfit and who would have to be there a few more months. But I was darn happy to get out of there," he recalled.

He got a jeep ride to an airstrip, and checked in for a flight on a DC-3 to Pusan. "I was astounded to see my skipper, Captain Harmon, was there for a flight out also. He asked me how in the heck I was going home so early. I told him that my ‘Truman Year' was about to be over." Schroeder said they turned in weapons and helmets, and filled out a form to take war souvenirs home. "My Russian 7.62mm carbine was of interest for evidence that the Russians were supplying weapons to the Chinese and North Koreans," he said. "I did some beating on the date of manufacture, and was able to bring it home. If we had any script, we turned that in for real money."

At Pusan, Schroeder joined a bunch of Marines and a few combat corpsman on the USNS Billy Mitchell, which was a troop transport. He knew only one other man on the ship. "This Marine and I had gone to grade school together for about two years," he said. "I asked him a question about his sister, whom I was sweet on in school. He disappeared to a different hold, I guess. I'll never know why he ‘bugged out' on me." Other than that baffling experience, Glenn's trip home on the Mitchell was upbeat. "My mood was definitely on a ‘high'," he said. "I'd managed to get out of Korea with all of my body parts intact, and only one minor wound." He said that he didn't do anything on the ship but "bug the sailors about their soft duty." His memories of the trip home were pleasant ones. "There may have been a little seasickness, but I didn't get seasick on the way back. The weather was great. We could see the wake of the ship all the way back to the horizon. It was an outstanding trip," he said.

The ship stopped in Kobe, Japan, to retrieve the sea bags that they had left there on the way to Korea. "I was shocked that mine could actually be found," remembered Schroeder. "I thought that it had gone into some ‘black hole.' All total, the trip home took about ten days. Schroeder said that seeing mainland USA was an emotional time for him as the ship drew near to land. "Spotting the Golden Gate Bridge and sailing under it was a sign that I was actually back to the States. We were met by a fireboat spraying water around, which was quite a sight. When the ship docked in San Francisco, there was a Navy band playing, but there wasn't anyone he knew waiting to greet Glenn when he disembarked from the ship. "After going down the gangway," he said, "I put down my sea bag and touched the dock. I don't know why. Maybe I wanted to find out if it was real." He was finally on firm ground. And that ground was the western shore of the United States of America. "The corpsmen were all mustered together," he said. "Those being discharged were put into one group—about eight of us as I recall. We were told to report to a sailor standing by a Navy bus for transportation to Treasure Island."

Schroeder finished out his time in the Navy at Treasure Island Naval Station while waiting to get discharged, by running around with seven other returning Korean War corpsmen. And, he admitted, he was definitely "testy". "We eight guys running around in Marine uniforms were a bunch of ‘aliens' to the swabbies. Many of the Naval personnel had no clue about what to do with us. They kept muttering about how we should be ‘with our own kind.' We got into a huge flap with the Charge of Quarters who would not give us liberty cards because we were wearing tan uniforms without jackets. He insisted that we had to have jackets to be ‘in liberty uniform.' We finally found a Navy officer who squared the guy away. We wanted to make certain that we were actually in the States," explained Schroeder. "We really didn't do anything special other than drink some beer."

The eight corpsmen reported to Personnel and explained that they were there for discharge. But their records had not caught up with them, not yet having arrived from Navy headquarters in San Francisco. "At the muster the following morning," said Schroeder, "a Chief Petty Officer put us all on a bus, because there was to be a work party. Those of us in Marine uniforms fell in at the rear of the column. The Chief was out in front calling cadence. All of us ‘Marines' left the formation after about a block and went to the snack bar."

Schroeder said that it took an inordinate length of time to get discharged, and during the wait he did not entertain thoughts of re-enlisting in the Navy. "Are you kidding?" he exclaimed. "Not in your wildest dreams." The wait for his discharge dragged on. "I was really steamed and called the poor personnel clerks every name except their own!" Finally, on 4 October 1951, he got his discharge, and headed for home.

At the time he was recalled for duty because of the Korean War, Glenn Schroeder only had two more quarters to finish a Bachelor of Science degree at the university. "I got off the bus at the Oregon College of Education (Western Oregon University), Monmouth, Oregon, waiving a wet discharge, wearing a uniform, and carrying all of my gear. I went to the football coach because I had one more year of football eligibility left. He hustled me to the Registrar's office. The Registrar said that I was one day past the deadline for late enrollment. I told him that I would carry only 12 credit hours, but he insisted that he would not let a senior jeopardize a GPA. Now I was really steamed at those Navy personnel clerks (better known as ‘feather merchants') for not knowing what to do with Navy guys wearing Marine uniforms!"

Glenn said that he knocked around a little, and sought help from the Veterans Administration program staff. "I discovered that I should be talking to a telephone pole. It would have been about as helpful. The VA person was NOT at all helpful," he said. "I'm still angry at that jerk! The ONLY thing he told me was to go to the State Employment Agency. They had a job planting forest in the Cascade Mountains, but I'd need a sleeping bag. I told the guy that I'd spent eight months in the hills of Korea, and was not about to go back to that kind of life, sleeping bag or no sleeping bag!" Instead, Glenn worked on his Dad's farm until January 1952, when he enrolled in college and completed his degree in June 1952.

That year, he worked in a cannery, processing cherries. When that work ran out, he ran a grain cleaner in a grain elevator until he had to report to his school district as a rookie teacher and coach. While teaching, he continued his formal education, and was awarded a Master's Degree in Educational Administration at the University of Oregon on 9 June 1957, having finished it in August of 1956. "In some respects," Schroeder said, "I think that most of the students on campus had no military experience. All of the World War II vets had graduated. The students seemed like little kids and couldn't comprehend some of the quirks I displayed, such as ducking upon hearing loud or unexpected noises. It is difficult to explain. They seemed to be as na¼ve as the personnel clerks on Treasure Island who had no clue what combat was like. I don't know how to put it, other than to say that they acted like ‘babes in the woods.'"

Glenn, now a combat veteran, found that he was no longer the carefree college kid who went along with goofy pranks. After Korea, he knuckled down to the books. "I was serious about studying and trying to improve my GPA," he said. "I looked forward sometime down the road to graduate school. I was much more cognizant of my surroundings, always looking for danger and ‘taking cover' when strange noises occurred. I guess I was much more aware than the crop of undergraduates at the time." Schroeder said that even the professors who had taught him before he went to Korea noticed a change in him. "They told me that I was now a serious student," he said.

Schroeder recalled that, "One person who I knew prior to leaving said that I had changed and was very serious. I should relax a little. He was a guy who worked on the school newspaper and asked me some questions for an article in the paper. I remember clearly that he asked me about the funniest thing that happened in Korea. I told him that NOT a G – D – thing happened in Korea that was funny!! He just looked at me and walked off. I yelled at him and said that two guys caught a Mongolian pony and brought it through the brush, but that our mine clearing team had all of our weapons drawn down on them. They threw up their hands and yelled, ‘Hey, don't shoot. It is only us!' Then I told him that those two dumb guys were complete idiots, we could have killed them, and that is not funny! He just said, ‘Yeh, I guess not.'"

During the course of his college studies, he married Eileea Joan Enstad at Dallas, Oregon on 9 August 1953. They set up housekeeping in Oregon and he taught seven years in Myrtle Creek as a 7th and 8th grade teacher, assistant high school football coach, and upper elementary school basketball coach. The last three years there he was a teacher/assistant principal, and had all of the band kids to free him for the administration assignment. In 1959, he left Myrtle Creek to teach in the Department of Defense Overseas School for the Army in Germany.

In Germany, he was an 8th grade teacher in Kitzingen the 1959/60 school year. The following year, he was teacher/principal at the school in Hohenfels, Germany. The third year, he opened a new junior high school with the elementary school in Straubing, Germany, serving as principal there for two years. During his second year of teaching in Germany, he and his wife Eileea were divorced.

He married Carolyn Jeanne Ledgerwood in Vienna, Austria on 14 February 1962. The next year, Carolyn and Glenn adopted a son, Jason Lee Schroeder, when he was five days old. A year later, they adopted a second son, Christopher Gray Schroeder when he was three weeks old. The couple also had a natural son, Peary Whitman Schroeder, born in 1965. All three sons were born in Germany during the years that Glenn was principal at the Giessen, Germany Elementary/Junior High School. In 1966, he resigned that position and returned to the United States, where he entered the doctoral program at the University of New Mexico. He completed a Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Educational Administration/Recent US History there on 6 June 1969.

After obtaining his PhD., he accepted a faculty position as Assistant Professor of Educational Administration and Assistant Director of the Educational Service Bureau at Temple University in Philadelphia. But, he pointed out, "One can't make a westerner like the east!!" He obtained a faculty position as Associate Professor of Educational Administration and Associate Director of the Educational Planning Service at the University of Northern Colorado (UNC) in Greeley, Colorado, beginning in the fall of 1971. He received tenure in 1975, and was promoted to full Professor in 1976.

For six years Glenn was the Director of an external master's degree program in Public Administration that his department at UNC operated at various military bases across the country. "The job kept me out of town many weekends," he said. "I suppose, in retrospect, that I settled on higher education as my main job. I enjoyed the graduate students, which were the only students I had in class, but missed the little kids and teachers in the elementary school. I didn't miss some of the junior high kids." On 12 August 1989, he retired as a formal educator.

Then he got a serious infection: the genealogy bug bit him. Since then, he has researched and completed six books on both the maternal and paternal sides of both his and his wife's ancestral lines. He also wrote an autobiography, and in the year 2000—when this interview was conducted—he was working on a seventh family tree book. The latter concerned two of his wife's ancestors, both of whom were West Point graduates and participants in the Civil War.

When he wrote his autobiography, he saw nearly fifty years later what he had not seen when he first returned to the States from Korea. "I was amazed to see the difference between a picture of me taken prior to shipping out, and one that was taken three days after my return," he said. "I had not noticed that ‘1000 yard stare' I had in the second photo. I was astonished to notice that when I put those in my autobiography." Going to Korea had noticeably changed Glenn Schroeder on the outside, as well as internally.

He said that his time in the Navy and in Korea didn't really shape his post-military life, but it did have a positive affect. "I could understand and relate to the military while serving as principal of DoD schools for kids of military in Germany and while directing a master's degree program and teaching graduate classes filled with military officers on military bases," he explained. "I think, in that latter case, the military personnel accorded me more respect for being a combat veteran than for holding a doctorate."

Thinking back on the Korean War's place in history, Schroeder said that, at the time, he was very na¼ve politically. "I had always agreed with George Patton that we should have brought our troops home via Vladivostok after kicking the heck out of the Soviet Union. I disagreed with Roosevelt, who let his advisors talk him in to giving away much of Europe to Stalin. With the Soviets supporting North Korea, I thought that it was time to draw a line in concrete over which they could not cross, so I did support sending our troops to Korea. Today, I would have opposed the move because the United Nations was involved, and I am NOT a fan of the UN. In fact, I believe that we should kick it out of this country and withdraw our support for it."

Schroeder said in the interview that he believed that the track record of that organization doing any good, except for sending money into ‘black holes,' is ZERO. "It ignores a fundamental right of all people and nations—the right of sovereignty," he said. "Secondly, if our Congress is not willing to exercise its duty under the US Constitution (Article I, Section 8) to declare war, we have no business sending troops against a country, regardless of its aggression."