"As a doctor, I had known death and dying stateside. But not on this scale. I guess we were all upset that all these young men were being injured and killed."

- Harold Secor

[KWE Note: Harold Secor served as a surgeon in the 8055th MASH Army Unit in Korea. The famed M*A*S*H movie and television series was styled after this MASH unit. Dr. Richard Hornberger, author of M*A*S*H, was a surgeon in the 8055th around the end of Secor's tour of duty in Korea. Dr. Secor completed the following memoir in Questions/Answers sent to him via US mail by Lynnita Brown.]

Harold E. Secor was born March 21, 1925, in Towanda, Pennsylvania, the son of Clare Logan and Mary Emoline Stoddard Secor. Clare Secor was an electrician and general contractor. Mary worked on proximity fuses at Sylvania Electric during World War II. Harold was the elder son of three sons born to Clare and Mary. His brothers were Albert M. (two years younger; served in the Navy in World War II) and Gordon S. (one year younger; served in the Air Force in World War II as a B21 engineer).

During his youth, Harold was a Boy Scout from age 14 through 18. He was a patrol leader and earned merit badges to the level of Life Scout. In addition to these activities, he held summer jobs after school. He worked with his dad as an electrician's helper, drove a grocery store delivery truck on Saturdays, and worked on road construction. When he was between the ages of 10 and 13, he mowed lawns. Harold attended Towanda High School in an accelerated group, graduating from high school in 1943 with many college level courses behind him.

He entered the Army two days after he completed his high school studies, leaving from his home in a Greyhound Bus with some of his high school friends. The bus took the group to Harrisburg, and from there they boarded a train to Ft. McClellen. "The train was made up of converted cattle cars," Secor recalled. "It was hot and dusty. We had a few stops for food and relief, but I didn't know any of the places. I was glad when we finally got to McClellen."

Even after all of these years, he remembers the first day at the camp. "I had a raincoat physical and was issued clothing, a Garand rifle, etc. I packed my civilian stuff and they mailed it home." The instructors who trained him as an infantryman were a mixture of World War II and pre-World War II veterans. "Others were almost as new as I was," he said.

According to Secor, basic training was 13 weeks They had poison gas training, used mortars, BAR's, Springfield rifles, and learned grenade launching. "We hiked twenty miles, camped out in pup tents, and planted grass," he said. "We were up each morning by 6, awakened by bugles. We brushed our teeth, shaved, and got to breakfast. We showered at night, and then had some free time before lights out to write letters, etc." Occasionally, the men in his platoon were awakened at night for KP duty or guard duty.

Food was fairly good and adequate at the camp, according to Secor. The men were served helpings of roast beef, chicken, potatoes, various vegetables and fruit. They received spiritual nourishment, too, because church was available.

The recruits were required to take marksmanship tests and tests in physical ability. They were also involved in a war game at one point in time. Secor said that he enjoyed the night patrol practice. He remembers watching "Mickey Mouse" sex education films, as well as films on weapons. These things were not difficult for him. The hardest part of his training, Secor said, was "trying to eat enough to keep from losing weight." He had entered the military during World War II, and never had any regrets for doing so. "Remember," he said, "It was worse being a civilian and being called a slacker."

Instructors whom he came to appreciate would not allow their men to be "slackers." They patiently taught the men how to survive, and Secor said that he appreciated their guidance. He said that one of the younger instructors was unusually strict and hard to get along with, but said that, "Most of the others were considerate of the fact that we were country boys." Punishment was usually push-ups or running, usually meted out as the result of being late for assembly. "Most of the group I was with tried to do well, so the punishments were few and far between," he said. "One time there was a lot of activity after lights out in response to some minor injustice. The whole group was called out and stood at attention about midnight for one hour. This disturbance was caused by one or two people, but no one told who, so we all stood one hour." He said that there were no real troublemakers among his fellow recruits. "Some were inept," he said, "but otherwise, they were not troublemakers. Only one didn't make it out of basic, and that was because of illness."

When basic training was completed, the men were shipped out to their various assignments. Secor said that he felt ready for combat, and that he was "leaner, tanned, and glad to be finished." Some men had leave, but Secor was not to have leave time until quite a while later. When he did go home, he wore his uniform and gave a talk to the local Lions Club.

Because of his standing among the others who took basic training at the same time he did, Secor was given the chance to attend the Citadel in Charleston, South Carolina for pre-med school. He was placed in a pre-professional training course in the Army Specialized Training Program to become a medic. The ASTP program was created by the government to assure that the country would not fall short of doctors and engineers. He spent two accelerated semesters there in the ASTP program. From there, he was sent to the University of Missouri to finish his pre-med requirements, also under ASTP. Secor said, "In what amounted to five semesters of accelerated education, I completed the required pre-medical courses which included everything from biology and organic chemistry to English Literature. We had classes six days a week. There was a minimal amount of military training. We were taking regular college courses from civilian instructors."

Eventually, Harold accumulated about 115 hours of pre-med studies. "We had classes six days a week and from about 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., except Saturday 8-12," he recalled. "P.E. courses were included. I needed a B or better to qualify for medical school," which he did. He was sent to Ft. Sam Houston as a medical corpsman for several months before being assigned to a medical school in the fall. "As a corpsman at Ft. Sam," he said, "I worked nights on a frostbite ward. This was the time I spent waiting to enter medical school at Baylor in Houston. The job was essentially nursing care for the patients on this ward." During the daytime, when he wasn't sleeping, Harold took flying lessons at Hurt Field, soloing in a Piper Cub.

In the fall of 1945, Harold was assigned to Baylor Medical School. The school had moved from Dallas and was in a temporary building formerly used by Sears as a warehouse. "The only air conditioning was for the lab dogs," he said. Secor lived in the Phi Chi fraternity house, and went to classes like any student. "We had anatomy classes using human bodies that were mostly unclaimed or donated. We smelled like formaldehyde most of the first year. Then we had physiology, neurology, obstetrics, gynecology, etc. for two years. The last two years included clinical work at Houston hospitals. We were in the permanent building the last two years I attended Baylor. Between the sophomore and junior years, I stayed in Houston and helped with the moving into the new building."

In his first year of medical school, World War II ended. He went to San Antonio, Texas, for his discharge in early 1946, but wore G.I. uniforms even after he was discharged, and then went through most of medical school on the G.I. Bill. In his senior year, his G.I. Bill benefits ran out, so he then borrowed enough money to finish and graduate. The fact that he had used government money to attend school for so many years obligated him to possible future military service, if called upon by the government.

In his sophomore year, Harold went on a blind date with a young lady named Shirley Marrs from New Gulf, which was about 50 miles from Houston. He was doing his junior year in medical school and she was training at Jefferson Davis Hospital as a nurse. As a nursing student, Shirley was doing deliveries and surgeries, and during this time she was required to live in the nurses' residence until her and Harold's senior year. The couple married on September 16, 1947. "We rented an upstairs apartment in Houston during our senior year," he said. "It had one bedroom and a kitchen on a porch. The bathroom was shared with tenants in another apartment." The apartment was located about a mile from the hospital and three or four miles from the medical school. The couple traveled around in a 1940 Ford the last year of Harold's medical schooling. "We graduated in late May of 1949--me from Baylor Med in Houston and her from Jefferson Davis School of Nursing in Houston," he said. "We put all of our possessions on the back seat of the Ford and drove to Sayre, Pennsylvania, where I had a year's internship at Robert Packer Hospital. When we came to the Texas state line, I asked my wife if she had her passport. She panicked, since she had never been outside of Texas. She really thought I was serious."

His internship was a general rotating internship--medicine, surgery, EMT, OB, neurosurgery, emergency room, ambulance duty, etc. The next year, Harold's residency in Obstetrics and Gynecology began. "While Shirley worked as a nurse and earned our living," he said, "I assisted the chief and delivered all the charity patients. We also did much of the care of babies at the Robert Packer Hospital. In the good old days, interns and residents weren't paid."

In June of 1950, war broke out on the Korean peninsula. Harold was in the midst of his residency in Sayre when he received a draft notice from Houston, Texas. While attending medical school there, he had registered for the "Doctor's Draft," so Harold was not surprised when he was called to active duty. "I accepted it as my duty as my family has done for three generations," he said. Harold applied for a commission and entered as a first lieutenant. In late June of 1951, he left for Harrisburg with two other doctors. They were inducted into the service and assigned to Ft. Sam Houston for training. "My wife and I went there in our 1946 Plymouth," he recalled. "Our possessions fit easily into the car. As an officer, I had to buy uniforms. I bought uniforms in Houston and left my wife with her parents in New Gulf. She was several months pregnant and had trouble with the heat." While in training in Texas, he was able to drive to New Gulf on weekends to visit her.

Having completed medical coursework and most of his internship by the time he was drafted, Harold was considered to be a doctor and didn't need medical training after induction into the Army. He worked as a corpsman during the short time he was at Ft. Sam Houston. The training program he attended in Texas was on the use of weapons. He said that during his limited training there, he gained some good medical experience. He also kept up on what was happening in Korea by reading the newspapers and TIME magazine.

Eventually, he was shipped to California to a base near San Francisco. On the train to California, he was assigned as the train doctor. His only patient was the daughter of one of the soldiers. "She had fallen off of a horse the day before, and had a concussion that was worrisome," he said. "She should have been in a hospital, but her family didn't want her to be left behind. She gradually recovered on the trip."

In California, Secor said that he was "at one of those bases with nothing green--just sand." He and another doctor shared a two-man room in a barracks. Harold had the chance to visit Oakland and San Francisco, and see the Golden Gate Bridge, Fisherman's Wharf, and other tourist sites before departing from the United States on an airplane operated by a private company under contract with the government. "It was one of those cost-plus things," he said. "If there was an oil leak, the government bought the oil. The airplanes were cargo planes with temporary seats. They only had weather radar. We stopped at Wake Island for gas. A storm had wiped out all the sheds, so all there was at the refueling area was a stack of 55 gallon drums. The runway started in the sea and ended in the sea."

On their way again, the plane stopped in Hawaii long enough for the passengers to get a cup of coffee and see a sign that said, "Aloha." From there, the plane flew on to Tokyo, Japan, where the doctors were to transfer to another plane to take them to Korea. One of his strongest memories of Korea is of seeing the impressive mountains of South Korea as his arrival plane flew over them. "I didn't make it on the first plane and had to hitch a ride in a C-47," he said. "A dentist and I had been too far back in the line for the first plane. We were dropped off in the southern part of Korea with no idea where we were to go. Things were rather confused at this point, and no one knew where anything was. We borrowed a convenient jeep and headed north. We tried to get a meal at a mess hall, but since it wasn't meal time, no luck. Transient officers had no clout. The mess sergeant told us that it wasn't a cafeteria." Secor finally found his unit near a small village north of Seoul. The motor pool redid the numbers on the jeep that Secor and the dentist had commandeered for the trip to their unit.

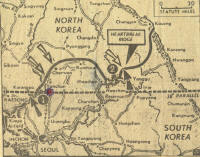

Harold Secor arrived at the 8055th MASH unit around the first of July 1951, and he remained there for 15 months. During the first part of his tour of duty, the two or three-acre unit was located near Uijongbu. Later, he was stationed in the Han River area. The unit was a compound of tents situated just south of the front line. It included living quarters, hospital areas, mess hall, guard shack, and generator shed. The hospital section had a receiving area where the ambulances unloaded. Also in this area were the X-ray and lab facilities and blood storage area. "Patients were examined, evaluated by X-ray, cross-matched for blood if needed, and moved to the pre-op area," he recalled. "Then as space and needs dictated, they were sent to surgery, which had three and later four operating tables. This was all in tents when I arrived. Later a quonset hut was erected for the surgery."

Harold Secor arrived at the 8055th MASH unit around the first of July 1951, and he remained there for 15 months. During the first part of his tour of duty, the two or three-acre unit was located near Uijongbu. Later, he was stationed in the Han River area. The unit was a compound of tents situated just south of the front line. It included living quarters, hospital areas, mess hall, guard shack, and generator shed. The hospital section had a receiving area where the ambulances unloaded. Also in this area were the X-ray and lab facilities and blood storage area. "Patients were examined, evaluated by X-ray, cross-matched for blood if needed, and moved to the pre-op area," he recalled. "Then as space and needs dictated, they were sent to surgery, which had three and later four operating tables. This was all in tents when I arrived. Later a quonset hut was erected for the surgery."

Doctors lived in four-person tents that were heated with an oil stove. In Secor's quarters, there was Secor from Texas; Captain Miles, a black doctor from Virginia; Lyle "The Duke" from Georgia; and Dr. Mike Saline from New York City. "We all liked and respected each other," he said. "We were all very fond of each other and got along with no troubles. My specialty, other than triage, was the treatment of closed fractures of hands. I told Captain Miles that if I ever needed surgery, I wanted him to do it. He was one of my friends and he was accepted as a good surgeon with no prejudice."

In Secor's tent, they were all friends who shared. "We ordered things from Sear's catalog, shared cakes and cookies that sometimes took guesswork to know which was which after the mail service crushed them, and even Captain Saline's lox and bagels." They enjoyed holiday meals together, and, though they had to work on their birthdays, receiving a card was a welcome treasure. They supported each other when there was bad news, too. "My wife didn't get her allotment check for several months, but we were able to handle that through the payroll section."

A constructed (and incomplete) list of 8055 MASH personnel who were stationed in Korea at the same time as Harold Secor was, is as follows:

Together, these doctors experienced a wide range of conditions while stationed in Korea. Certainly, one of the unpleasant things that they collectively experienced was the cold. The stove in their tent was set in a sand box, and heated with fuel oil. "Fuel oil is solid at 20 degrees below zero," Secor said. The stoves could prevent frostbite, but they couldn't actually keep the tents "comfortably warm." The floor of the square, four-man tent was sand until they got straw mats later on. Nurses had similar facilities. Officers had a row of tents with four men in each and enlisted men lived in long tents. Secor said that when he first joined the unit, all the doctors were in the same big tent and the nurses were in a similar type tent. Corpsmen lived in big tents, too. "Restroom facilities were rather primitive," he said. "There was no roof early on, but conditions improved slightly later." Summers were hot and winters were cold. It was impossible to bundle up to keep warm when working on patients.

He said there were perhaps 30 corpsmen, ten doctors, ten nurses, one dentist, two service corps officers, and about 30 Koreans assigned to his MASH unit. Several jeeps, two ambulances, and three or four trucks were also assigned there. The 8055th was generally four to five miles behind the front lines. "If they pulled back very far, we were on the enemy side," Secor recalled. "That happened at least once. We had a mine field in our front yard. There was always some danger, even from our own artillery firing over us. We had sand bags around the patient tents to stop stray bullets." Secor noted in a Daily/Sunday Review article that one day, "a bullet zinged into the mess tent, hit a post, and splashed into a cup of coffee." He said, "This was one of the accepted things that it didn't pay to dwell on."

Secor explained that single-tent battalion aid stations gave only first aid and then shipped the wounded back to the MASH units. "We did definitive surgery," he said. "We cleaned and closed wounds, treated fractures and illnesses, and did some rehabilitation." He said that a MASH unit was a hospital, complete with a post-op section that served as an intensive care area. The makeshift hospital was housed in long, connected tents with dirt floors and all, but the only thing that the medical personnel didn't do at a MASH was long-term care. "We saw patients with meningitis, measles, etc.," he said. "Quarantine would have been a joke, although I did establish a quarantine area one time to treat the Korean workers who had been diagnosed with TB".

Secor explained that single-tent battalion aid stations gave only first aid and then shipped the wounded back to the MASH units. "We did definitive surgery," he said. "We cleaned and closed wounds, treated fractures and illnesses, and did some rehabilitation." He said that a MASH unit was a hospital, complete with a post-op section that served as an intensive care area. The makeshift hospital was housed in long, connected tents with dirt floors and all, but the only thing that the medical personnel didn't do at a MASH was long-term care. "We saw patients with meningitis, measles, etc.," he said. "Quarantine would have been a joke, although I did establish a quarantine area one time to treat the Korean workers who had been diagnosed with TB".

The doctor's day started early. "I was usually up and shaved and brushed by 7 a.m. and off to relieve the man who had been on night duty," Secor recalled. He and the other staff usually worked in tee shirts and green trousers, even in cold weather. Leisure time was limited to a little bit of baseball (never football and never with any genuine "competition" in mind), reading, listening to records, and sleeping. One Korean patient also was "patient" enough to help the doctor learn Korean. A couple of times some old vaudeville actors came in the MASH area to put on shows. "They had some good acts," Secor remembered. "They sang, danced, did acrobatics, etc." Secor smoked to while away the time during his stay in Korea, and did a little drinking as well. When Captain Ready bought his officers a bottle of White Horse one time, Secor made it last a long while. He didn't try his hand at gambling, though. "I couldn't afford it," he said.

A MASH unit differed from a battalion aid station in that battalion aid was a first aid station. A MASH unit in the Korean War was equipped as a full field hospital. "We had a laboratory, X-ray, triage area, surgical hut, etc.," Secor said. "I was a World War II salt, and so was the CP. We had many of the older doctors at the 8055th. My job was in pre-op. Some of my corpsmen had been trained as truck drivers, but I retrained them for medical duties such as X-ray technician. This freed up the trained doctors and other regular medical staff to concentrate on the wounded. The enlisted men knew I had once been an enlisted man, too, so they worked well with me. I gave the enlisted men's club my beer ration (6 cans of beer two times a month) and they invited me down once a month for a beer." Secor also ran the receiving area with Mike Saline. At this triage area, fractures were stabilized, fluids were started if needed, X-rays were taken, pressure dressings were applied to stop the bleeding, etc.

As if handling all of these casualties were not enough training, Secor said that there was a "38 Parallel Medical Society" that met at least once a month to discuss medical issues. It gave the MASH doctors an opportunity to talk medicine while also providing a little social activity. "We had members from the British units, Indian units, and other MASH units. We even invited a Chinese doctor that I accidentally contacted on the telephone line, but he couldn't get away to come." The participants discussed the treatment of some of their patients, and they talked about their experiences in Korea. At one of the meetings, it was learned that a British unit was short of corpsmen, so the 8055th loaned one of theirs to help them out. Once Secor even had the opportunity to attend some lectures in Pusan. He went by train as a representative of the 38th Parallel Society and remembers that they stopped at sunset to avoid possible bandits and people walking on the tracks.

In spite of the occasional diversion such as the medical society and the invitations to the enlisted men's club, the vast majority of Dr. Secor's time was spent with his patients. In the receiving area, incoming wounded were seen and coded according to the severity of their wounds. When patients were transported by helicopter, the copter landed in a field a short distance away from the regular triage area at the front where ambulances came in. Clothes were removed, wounds were evaluated, and sometimes the wounded were treated there. More serious ones were X-rayed and assigned urgency levels and sent to pre-op. "If they had a hang nail, treatment wasn't urgent," Secor explained. "If they had an abdominal wound, it was urgent. A sucking chest wound needed care right now. In receiving we controlled active bleeding before sending a patient to pre-op. Also in receiving, we splinted, closed fractures of the hand, and released men back to duty. We splinted extremity fractures and sent them to pre-op. Supplies were generally adequate. Blood took too long to get to us at times so we typed members of a nearby engineering company, and drew blood from them as needed."

Secor went on to say that charts were kept on each patient. "We all recorded on a chart what we had done for a patient. We had a small office staff with our own enlisted clerk/Radar O'Reilly-type who kept other records. We probably did better than some stateside hospitals. It was vital that we did so that stateside hospitals would know what had been done to patients being sent to them from Korea." He said that card records were kept on all patients and more extensive charts were kept on surgical patients. Patients needing follow-up care (most of the surgical patients) were shipped to the big evacuation hospital in Seoul and on to Japan and the United States. "We were probably the best medical unit available to frontline troops," he said. If they got to our unit alive, less than one percent--or possibly two percent--died. The doctors and nurses were conscientious and competent, but they usually didn't stay at the MASH unit for very long."

As good as they were, they were still willing to accept advice from others with more expertise in a certain area. "One time a radiologist from Johns Hopkins came over and spent a month reading films and checking our processing methods," Secor said. "I guess we were doing things the right way, because he returned to the States."

Every once in a while, the staff became the patients. There was one administrative officer in particular who tried every way to go home and finally committed suicide with a .45. When he died, the company flew the MASH unit's American flag at half mast. Also, the first dentist that Secor remembered was in the MASH unit was a dentist who drank so much that he was finally carried out on a litter.

MASH personnel treated South Koreans, G.I.'s, British, Turks, reporters, etc. Sometimes, however, patients were not allied troops. Twice Dr. Secor performed surgery on company pets. "The Turks had a pet deer," he explained. "It had hurt its leg, and somebody put a cast on it, which was about the worst thing they could have done. The deer had a very thin and fragile leg and the cast was heavy. I had to amputate the deer's leg in order to try to save it. It survived the surgery, but was too weak to live for very long and it died. The Turks gave me a bottle of Turkish drink for trying to save their mascot's life." Another time, the MPS brought their dog to Dr. Secor. The dog had been hit by a car and had a broken femur. "I used 1/16th inch Kirschner wires, putting three down through his femur," Secor said. "Not long afterward, he was up and running again."

"We had enemies in the MASH compound as patients, too." Secor explained. "I always kept my cap turned up to hide my captain's bars. One time a North Korean managed to keep a pistol hidden until he was in surgery. When he was in post op, I asked him what he intended to do with the pistol. He said that he had planned to shoot the first officer he saw. Because I had the habit of hiding my rank insignia from other officers by turning my cap bill up, that probably saved my life because he could not see it."

Other enemy got into the compound, too, Secor said. "We found out later that the chief honcho for the Korean work force was a Chinese colonel. Before Christmas, a Chinese slipped in and left Christmas cards for us that said, "We the Chinese people wish you a happy holiday and wish it could be under different circumstances." To get into the camp, the Chinese infiltrator had to go through a mine field. Unfortunately for him, he did not make it back through the dangerous field. He lay dead in the field the next morning.

The MASH unit the minefield protected had Korean corpsmen of all ages to help with the multitude of duties that were daily routine there. One was a Korean lawyer. "There was one young man who did our laundry and made sure our tents didn't fall down," he said. The doctors and nurses even came to know their Korean patients and to follow up on their care. According to Secor, one of the atrocities that he knew was committed in Korea was the way Korean patients were treated in their native hospitals. "If a relative didn't come along and furnish food, the patients starved. This happened to one boy we transferred to a Korean hospital," he said.

As a doctor, Harold Secor had known death and dying stateside. "But not on this scale," he said. "I guess we were all upset that all these young men were being injured and killed. The Baptist minister we had for awhile had a breakdown and was sent home. I wasn't Catholic, but my friendship with a young priest helped. We counseled each other. It was a no-win war, but at least we did preserve South Korea. I knew that fighting in Korea was something we had to do. What upset me the most was when we got fixed lines and we weren't allowed to advance beyond certain levels. I thought it was a shame that so many young men had to die just to hold the line."

On a lighter note, one time the priest and Secor found a boat or junk on the river bank. The two of them talked about fixing it up and going AWOL someday. One morning, the young priest came to him to tell him, sadly, that their escape plans had been thwarted when the junk floated away during a heavy rain in the middle of the night.

There was no shortage of patients for the staff of the MASH unit to attend. "During the first winter, the Cav unit ahead of us was overrun and had a bunch of wounded," Secor recalled. "It was freezing cold weather and they were in their sleeping bags to keep warm when they were overrun. The Chinese were better dressed for winter, and they attacked the Cav Army unit," Secor said. "They apparently shot more to wound than to kill, so we were swamped with wounded still in their sleeping bags. The survivors were all brought in at the same time. In two days time we treated over 200 wounded and during that time, strangely enough had treated 200 before we lost one. There was one hill that was repeatedly taken and lost and this always kept us busy. Most wounds were fragment, bullet and fractures. Head and cord and nerve injuries we sent to our sister unit to the east. They sent us the vascular problems, and we sent them the neurosurgical patients. We all did general surgery." There were about four MASH units spaced across Korea, explained Secor.

"I remember two patients especially," said Secor. "One was the North Korean with the gun and the other was a British officer who wouldn't let us treat him until we had taken care of his men. I also remember a 20-year old who suffered a massive coronary occlusion and died over a 36-hour period." According to Secor, there were times when other types of injuries occurred as well. "Other times bouncing betty mines caused damage," he said. "If they were standing on it when it exploded, the foot and lower leg were smashed. Otherwise, it came chest high and exploded."

At one time, a human interest story associated with Secor's MASH unit had the potential to cause quite a stir back in the States. "I remember one patient," Secor said. "He was a 17-year old with serious, but non-fatal wounds. A wealthy woman in the States had given a pint of blood and hired a reporter to follow it to Korea and to a patient. I found this nit a good match and started it on this patient. The reporter wanted to be sure the patient would live, and then panicked when he found out his age. He said, 'We have been telling people that only soldiers over 18 are being sent to Korea.' I told him to just write it up and not mention the age, which he did. My wife mailed me a copy later."

In an article by Nancy Coleman in the Daily/Sunday Review newspaper (December 22, 1998), Secor recalled another patient in an unusual circumstance. "One soldier came in with a copperhead bite on his finger. Secor thought he'd have to amputate, but he had more serious cases and decided to wait. In the meantime, a sort of black husk formed around the swollen finger. One day, the husk split and peeled off. The soldier's finger was fine. 'He got well by himself,' Secor said, proving that, 'If you don't know how to doctor someone, don't do anything.'"

The worst case that Secor had to deal with in Korea was someone who had dropped his rifle. "He was shot through the pelvis with disruption of the lower bowel," Secor said. "It was almost impossible surgery. Drainage and antibiotics couldn't save him."

At one point, a patient was brought in because his sergeant thought he was a psychiatric problem. "I noticed a small tear in his shirt and opened it," Secor recalled. "He had a through chest wound with no external bleeding. The wound was rapidly filing his chest with blood. We got him to surgery, drained his chest, and gave him a transfusion. That not only cured his 'psychosis', it also saved his life."

Unlike the staff in a stateside hospital, Secor said that MASH personnel managed to save a large number of lives under adverse conditions. "I remember one patient who arrived in January when it was 20 below zero," he said. "He was cold and pulseless after his copter ride. With two units of blood and warming, a pulse became palpable. When he finally woke up he said, 'I thought I was dead.'"

Secor said that the MASH personnel always made do and gave good care. "We salvaged one of our operating tables from a bombed out Korean hospital," he explained. "We used foil from X-ray packs for X-ray shields. To scrub up, we used five gallon cans with truck valves and tubing for faucets. These cans were located on a shelf above our scrub sinks, which were big pans with drains installed."

For Secor, the hardest part of the job was just the daily living. "I regretted being so far from home," he said. He also said that he didn't like having to heat water in his helmet on the tent stove to wash and shave as best as he could while waiting for the shower unit to come by. In addition, he got tired of eating chicken every day. "We had Class A rations so the patients could have a good meal," he recalled. "Most of the time it was chicken and mashed potatoes and some vegetable. From before Thanksgiving until after New Year's it was turkey. While I was in Korea, I did fine with this diet, but when I got home, I wouldn't eat chicken for about two years. One time one of the officers got some beef steaks. We built a fire, roasted them, and ate them. It was the best thing I ate while I was in Korea. The second best was when my aunt sent me a can of ham hunks. I missed red meat most of all." Still, according to Secor, his tour of duty in Korea was enjoyable in other respects. He said that the medical experience he received there was invaluable.

On occasion, he also had the experience of seeing how the Korean people lived. "We had a Korean work force and one was our house boy, who did our wash and other things. He was a good boy. There were native houses nearby. I noticed that they had flues under the houses for radiant heating, but only a straw roof overhead. A favorite native food called kimchee was a homemade cabbage, pepper and oyster combination that was stored in a large buried container until it fermented. I remember that the odor was terrible. It would curl hair a mile down wind when the container was opened."

The GI's helped provide clothes for the local children. "We clothed them in material from GI blankets," Secor said. "The rear seam in the trousers was open so all they had to do was squat for elimination. All of them appeared to be well fed in the vicinity of the 8055th.

When new GI's arrived, the Koreans greeted them with the words, 'Me Gook.' The arriving GI's thought that the Koreans were referring to themselves as gooks, but actually 'Me Gook' meant 'the strangers from America.' "This made for misunderstanding." Secor continued, "It was a beautiful country with people who were apparently nice folks."

When new GI's arrived, the Koreans greeted them with the words, 'Me Gook.' The arriving GI's thought that the Koreans were referring to themselves as gooks, but actually 'Me Gook' meant 'the strangers from America.' "This made for misunderstanding." Secor continued, "It was a beautiful country with people who were apparently nice folks."

While there were always at least a few patients at all times in the MASH unit, sometimes it was "quiet" on the frontlines. "On these quieter days, I could sometimes get away to shop in nearby villages or in Seoul," he said. "I bought things like mats for the dirt floor in my tent or some interesting object to send home. Then there would be a big push and we might get 200 patients in 24 hours."

According to Secor, they had all sorts of excitement at times at the 8055th. "Bed Check Charley would come over at dusk and drop hand grenades, rocks, etc.," he recalled. "He had an old bi-plane--probably from the 1920s and probably Russian. Sometimes shells came in nearby. Some were ours and some were the enemy's. I tried to get pictures of some of them. One of the PX officers developed a heart problem and I treated him with no record because he wanted to stay in the service. He recovered well and later got a Nikkon camera for me."

Not just patients came and went in the 8055th, either. Visiting dignitaries arrived now and then, too. "Some visitors to the MASH unit were welcome and some weren't," Secor said. "Various generals visited our unit. If one in particular came by, I made sure my cap was turned up so the silver bars didn't show. When he asked where our officer was, I told him I didn't see him. If he asked where the CO and exec were, I told him they were taking a shower. He usually got mad and left."

According to Secor, most MASH units were set up a little further back from the front lines--but close enough to receive wounded in a timely fashion. "We were usually not a target for the North Koreans," he said. "But one time I noted to an ambulance driver that the wounded were coming in from the south instead of the north. He told me the front line had withdrawn a couple of miles to our south and nobody had bothered to let us know. We were just hung out there in enemy territory for a couple of days before the allies moved forward again." Another time, he and his driver took a wrong turn in the jeep and got too near the front lines. According to Secor, it was a court marshal offense for a medical officer to expose himself to enemy fire.

This is a safe conduct pass showing

the American side & the Korean side of it.

Dr. Secor was "hung out there" one other time, too. He was left in the dark over what was happening on the home front (his own home) in Texas. When he left the States, his wife was pregnant with their first child. When the baby was born, his mother-in-law sent a telegram to Secor to tell him about his newborn daughter. Unfortunately, he didn't get the telegram in Korea. His fellow doctors teased him that perhaps his wife was carrying an elephant since the gestation period seemed so long. Harold was not to know that Leslie Frances Secor (named after Shirley's father) had entered this world weeks before. When the telegram didn't seem to work, Shirley even asked an amateur radio enthusiast to try to reach the 8055th in Korea. In the end, she had to use the slow U.S. mail service to inform her husband--stationed thousands of miles away in Korea--that he was the father of a healthy baby girl. "I only saw the Red Cross and Salvation Army in the States," Secor recalled. "It took over a month before I knew I had a daughter and my wife was okay."

During her husband's months in Korea, Shirley lived with her parents. "It wasn't a hard thing for me to do," Shirley recalled. "My parents were nice people. They wouldn't take any money from me for rent, so I was able to save the money Harold sent home from Korea."

Living in New Gulf, Shirley Secor was not the only local who was aware there was a war going on in Korea. "My father worked for the world's largest sulphur company during the Korean War," she explained. In fact, just about everybody who lived in the private community of New Gulf worked for Texas Gulf Sulphur. "Sulphur was used in the making of ammunition, so there was lots of security in town," Shirley recalled. "They had patrolmen out checking everybody new who came to town. They checked ID's to find out where they were from and where they were going." Whereas the rest of the United States had a low awareness of the Korean War, Shirley lived in a community that very much understood that a war was going on, and Shirley's husband was in it.

Only for a short time was Harold out of the war zone. He spent about a week--including coming and going--in Japan. He went to Tokyo, and then on to a resort hotel called the Fugi View Hotel, where there were "good meals, a real bed, and nice surroundings." When he was in the Far East, Harold didn't have much luck with telegrams and such, but his wife was in his thoughts. He went antique shopping in Tokyo to find that perfect gift for her. "I bought some little ivory animals like birds and such," he recalled. "I also bought silk shirts for the two of us. I decided not to buy the traditional gift of Noritake china, because I found out that you could get it just as cheap or cheaper in Houston. I bought some pearls from Nikimoto, and sent home a Saki bottle and matching cups. Only the bottle and one cup made it home in the mail in one piece."

With limited funds to spend on presents, Harold found a little antique shop in Tokyo. He said that he looked in all the cases, with the proprietor of the shop following behind him. Before she could ask, he anticipated the question the shopkeeper was going to utter: "What you do, GI? Just lookie lookie?" Secor said, "At that time, ivory was fairly inexpensive and I had my eye on a Japanese Hoti god. Hoti was the god of children and presents. She told me that it cost $25.00, but I told her that was too expense. She repeated that $25.00 was the price. I knew that it was worth far more than that," Secor said. "So I paid it. She just forgot to barter." Both the little ivory animals and the Japanese Hoti doll are still in the Secors' home, treasured gifts from the Far East brought home as souvenirs of his trip to the Orient. After this short respite, he was willing to go back to work in the 8055th.

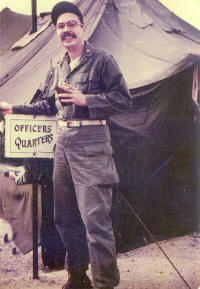

Toward the end of his stint in the 8055th (June 1951-September 1952), the moustached Dr. Harold Secor (Baylor College of Medicine 1949) and equally moustached Dr. John Innis (Baylor College of Medicine 1949) befriended a new arrival by the name of Dr. Richard Hornberger. There is little doubt that many years later, Hornberger remembered some of the war stories that he had heard from Dr. Secor and Dr. Innis when he first arrived in Korea. He used a version of them later in his civilian life, when Hornberger wrote a fictional book under the pseudonym Richard Hooker. His book was entitled, "M*A*S*H." Originally not too successful on the publishing market, the light-hearted novel later became the basis for a hit movie and long-running television series about a fictional MASH unit in Korea.

While some Korean War veterans think that the M*A*S*H series trivialized the war, Secor said he enjoyed watching it and thinks that most veterans of the real MASH accept the fact that it was a fictional book. "Hollywood's M*A*S*H was much smaller," he said, "But it maintained the same general spirit. I enjoyed watching M*A*S*H the movie and the television series. At the 8055th, we could all be funny at times, particularly one of our frequent visitors from the Indian Ambulance Corps. Captain Ready was always funny and upbeat. The first time we met him, he stuck his hand through the tent flap, waving a bottle of White Horse scotch. We responded with, "Hello stranger!" Some of the funny aspects of M*A*S*H made him laugh as he thought back on some of the antics he witnessed and participated in while at the the 8055th, but he also occasionally saw the serious side of a real MASH in the Hollywood production.

Secor believes that the personnel serving at the 8055th MASH in Korea were the models for a number of characters in Hornberger's book. He thinks that he and two other doctors in his tent were Hornberger's characters Hawkeye and BJ. The 8055th's very capable, blond-haired head nurse (Captain Dixon) was a Major just like the movie's Margaret "Hot Lips" Hoolahan, but she was not anyone's girlfriend. "She never acted like the movie or series portrayed her, so she was probably embarrassed by the character," Secor said. "There were only American women as nurses and they were hard-workers. Only one of them was suspected of being a naughty street lady, but she was not a nurse from our unit."

There was a short, dedicated company clerk with Radar-like qualities in the real 8055th. Surgeon John Lyday was a real "Trapper John" type individual stationed in Korea The 8055th also had about 12 gay men living in one tent. He said that one of them was "the queen of the bunch, who dressed as fancy as he could." Secor thinks that the cross-dressing Corporal Klinger was fashioned after this true-to-life person at the 8055th.

Even some of the scenes in the movie reflect life in the real 8055th. "One time I made a weird little chair from salvaged plywood and canvas," Secor recalled. "In the movie, there was a chair just like it set up on a fuel drum." According to Secor, just like in the M*A*S*H movie and television series, some of the clothing and accessories worn by the MASH personnel in Korea was not exactly regulation. "People wore whatever was comfortable to work in. Some had golf shoes," he said. I wore cowboy boots."

Although Harold knows that he met Hornberger at the end of his tour of duty, he can't even remember what Hornberger looked like now. "I just remember that he was young and new, and I think that his writings and the movie and television shows helped America's image."

Telegrams and mail arrived in an "iffy" manner at best during those days. Even his going home orders were mixed up. It took him two days to find out that he was scheduled to leave. "I walked by the company clerk in the mess tent and he whispered that my orders were in," Secor said. "By the time I got from there back to my tent, the other doctors knew that I was heading for home. I was the first to be sent back home and one of the group was worried about who would replace me. 'We can't have just anybody', he told me.

From the MASH unit, Secor went by truck to Seoul, and then he took a short flight to Japan. From Japan he went back to the States by troop transport. "Coming across the Pacific Ocean was something else," he recalled. "The first mate stayed drunk and one time we woke up and the ship was listing 15 degrees. It was dead in the water until they got the problem solved."

When Harold Secor's ship docked in Seattle, Washington, he wired home to his wife that he was on his way. However, so many had signed up for an airline flight that he had to take a Pullman train. "We rode down through the Rockies, across the Plains, and in to Houston." While in North Texas, he stopped at a restaurant and the man sitting on the counter stool next to him recognized him as the doctor who had treated him in Korea. Not long after, he was reunited with Shirley. Her parents had taken her in to Houston where they met Harold at the railroad station.

Dr. Secor finally got to meet his "baby" daughter (the first of three) when she was 11 1/2 months old. For Leslie Frances, her father's homecoming was somewhat scary. To her, "Daddy" was a picture on the wall that she kissed every night before going to sleep. But it didn't take too long for her to come around. Her in-person daddy purchased a coveted tricycle for her, and he took the time to help her learn to ride it.

The family moved to Houston and, with the help of Harold's brother, found a nice apartment. The apartment was big enough to house Harold, Shirley, Leslie, and Harold's brother. The latter was a hospital furniture salesman who had been transferred to Texas. He paid part of the rent money on the apartment during the months he lived there. All total, the Secors lived in the apartment for five years.

During that time, Harold finished his ob/gyn residency in Houston. Since his brother was familiar with hospitals in the area, Harold made trips with him to check out the facilities when he was trying to decide where to set up practice. Shirley's sister, Lola Phillippi, was a nurse at Rugley and Blasingame Hospital in Wharton. She mentioned to the obstetrician there that her brother-in-law was looking for a place to practice. They called him down for an interview, and he got the job. For the next 30-plus years, Dr. Harold Secor practiced as an obstetrician/gynecologist there. He was on call for his patients 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

When he retired at age 62, Secor served as Medical Director on the construction site of the South Texas Nuclear Plant. Currently, he teaches anatomy and physiology part-time (two nights a week) at Wharton County Junior College. His students are nurses and others going into some field of medicine.

Outside of teaching, Harold keeps busy in other ways, too. Years ago, his father put the family's old kitchen clock into the attic because it had stopped running. Harold took it out and repaired it with his skilled surgeon hands. Now he is an avid clock collector and an active member of the National Clock and Watchmakers Association. He is also a member of a radio control model airplane club, and is an active member of both the local American Legion post and the First United Methodist Church in Wharton. He does lots of woodworking, building everything from clock cases to furniture--including a special loveseat for his wife. His three daughters have also given him four grandchildren and three great grandchildren, and he is proud of them all.

For a few years, he sent an annual Christmas card to Dr. Mike Saline, but has lost touch with him since. He has never attended a unit reunion or made a return visit to Korea. "When I was in practice," he said, "I could never get away." Actually, now that he is retired, he still can't get away. He's busy with his teaching, with attending meetings, and with a myriad of other activities.

"It's been a full life, and I'm not through with it yet," he said in an interview with Baylor College of Medicine alumni newsletter staff. "I owe a lot to the service. It gave me my career." He has a display case with an Army commendation medal, Korean service medal with two stars, and other medals in his home, and he still occasionally watches re-runs of M*A*S*H, laughing at the comical antics of the surgical staff there. Though some of the Hollywood characters are 180 degrees from their real personalities, there are aspects of the movie and television series that bring back memories (fond and otherwise) of the war-torn country of Korea and the months that Dr. Secor served there with the 8055th MASH.