Yes, we wanted to go to war. We were young and stupid then, and being Marines we thought we were invincible. We quickly learned otherwise when we went ashore at Inchon and found out that bullets fly both ways.

- William Sports

The following is the result of an interview between William Sports and Lynnita (Sommer) Brown that was conducted via U.S. mail. in 2001. Mr. Sports did not have a computer at the time, so he painstakingly answered dozens upon dozens of questions by typing the responses with the use of a manual typewriter. When asked if the interview had been difficult for him, he said, "Somewhat, yes. It brought back things to mind--bloody things I had just as soon forgotten. However, I knew this when I agreed to do the interview." William Sports died on June 19, 2012 in a hospital in the town of his residence.

My name is William Dudley Sports of Effingham, South Carolina. I was born on April 11, 1929 on South Island off the coast of Georgetown, South Carolina. My parents were Charles W. and Mellie C. Gibson-Sports. Dad operated a gantry crane in the Charleston, South Carolina Navy yard during World War II. Prior to that he was manager of Tom Yawkey's South Island. Yawkey owned the Boston Red Sox. He later gave South Island to the state as a wildlife preserve. My siblings were Cathrine, Charles Jr., George, Anne, Bertha, Margaret, Mattie, Margie, and three brothers who died at birth. Four of them were older than me and seven were younger. I came between Anne and Bertha.

I attended grade school in Georgetown, and received my G.E.D. years later while in the United States Air Force. While attending school, I worked some in an old country store, getting orders together and delivering them on my bicycle. I also did the cleaning up. I had no time to be in scouting. I worked as much as I possibly could.

I grew up during World War II. My brother Charles Junior was with the 1st Army when it went ashore at Normandy. My brother George was in the Army Air Corps. I remember collecting rubber, tin, aluminum, and anything we could find made of metal for the war effort. Although I had two brothers in the Army, I thought the Marines were the "one and only". A friend and I dared each other to join. I got in but James Stidham, my closest childhood friend, didn't. We were going in together, but he flunked the eye exam. My parents were not happy that I had joined the military--especially the Marines. I persisted and they gave up and signed. I was just 17 years old when I joined the USMC on October 20, 1947.

There were a dozen or so on the bus that took me to Parris Island (the toughest boot camp in the world) via Fort Jackson, South Carolina. I knew none of them.

In the very first moments that we arrived at Parris Island, a drill instructor (DI) came on the bus screaming and cussing and calling us all kinds of names. He told us that he would be our mamma for the next nine weeks. The only DI that I remember by name was Corporal Lenz. Our senior DI was a World War II vet. He was, indeed, mamma, compared to Lenz.

In the very first moments that we arrived at Parris Island, a drill instructor (DI) came on the bus screaming and cussing and calling us all kinds of names. He told us that he would be our mamma for the next nine weeks. The only DI that I remember by name was Corporal Lenz. Our senior DI was a World War II vet. He was, indeed, mamma, compared to Lenz.

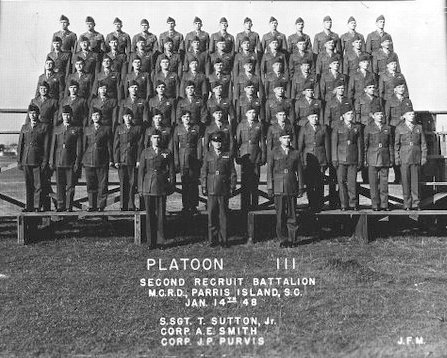

If I remember correctly, boot camp was nine weeks and I was in Platoon 111. Our heads were shaved, and our clothing, shoes and field gear were thrown at us. Everything was too big--for me, anyway. We put everything into our seabag, except our rifle, marched to our barracks, and were taught how to make a bed with hospital folds drawn so tight the DI could bounce a coin off of it.

Our days were regimented. We took showers at night and then were up at 0500 by lights coming on and the DI blowing a whistle and yelling. We made our bunks, washed and shaved, fell out for roll call, and had physical training. We were then marched to chow. If we let the mess hall staff put anything on our tray that we didn't like, we had to eat it anyway. All trays had to be clean. The barracks were kept clean by each man keeping his own area clean. If anyone failed to keep his area spotless, he used a toothbrush to clean it the next time. In the evening, lights were turned off at 2200 hours, but sometimes the DIs got us up to go out for exercise, close order drill, or a 20-mile hike. They needed no reason.

Corporal punishment was sometimes used. In 1947-48, a DI could grab a boot and slam him against the wall, throw his rifle at him, or even knock him on his butt. They only did this to screw-ups, however. Those who were too slow or who did not follow orders paid the price. I made the unforgivable sin of calling my M-1 rifle a "gun" to the DI once. We put a table in the middle of the barracks and I had to stand on the table with my rifle and repeat this two-liner over and over for an hour while pointing to the appropriate item (my weapon or part of my anatomy): "This is my rifle, this is my gun. This is for firing. This is for fun." I learned the difference during that hour. That was the only time I got into trouble with the DI. Another "shithead" lost the key to his foot locker and he took my place on the table. His two-liner was this: "I'm a shitbird from Yemassee, because I lost my locker key." I'm sure he learned to keep up with his locker key after that. One boot caught smoking in the head had to dig a hole 2x2x2 feet, then bury the butt and dig it up the next day with the DI watching. One boot broke a window. No one would tell on him. The DI got us on the parade field, rifle at port arms, and ran us around it six or seven times. The DIs had to be strict. Their discipline was not only individual, but also a collective type. They said it was to teach us teamwork. If one was in trouble, all were in trouble. We all made it out of boot camp, as I remember.

We were fed well in boot camp, though the taste was kind of bland. We were fed the usual soups, stews, pork chops, and yes, steak, too. We were also served vegetables in season, potatoes, and, of course, fish on Friday.

In classroom we learned the Marine Corps history and traditions. We saw weapons films, a few battle films, and films about Marine and Navy heroes--General Vandergrift, Chesty Puller, Admiral Nimitz, and others. The ones that stuck out in my mind--and still do--were the informational ones about General Vandergrift and Chesty Puller. The general was Commandant of the Marine Corps when I enlisted, and I served with Chesty in Korea prior to his becoming a general. Outside of the classroom we learned discipline, how to march, how to take care of our weapons, and how to fire on the range. We had to be qualified with our weapons, gas mask, weapons cleaning, bayonet, and hand-to-hand fighting. For the gas mask, we entered a chamber filled with gas, with our mask on. About a minute later we took off the mask and had to sing the Marine Hymn before we exited the chamber.

Parris Island was a low, salt-water, marshy island surrounded by water in the Beaufort area of South Carolina. Sand gnats or fleas would get on us and bite like crazy. We couldn't move to get them off so we just endured. When those gnats were biting and when I was showing everybody the difference between my rifle and my gun, I was sorry that I had joined the Marines. But near the end of boot camp, when I knew that the DI's training was to help me stay alive in combat, I came to appreciate my drill instructors. The training paid off for me in Korea. There is absolutely no doubt at all in my mind that I am alive today because of my boot camp training. In combat my mind seemed to bring back things we were taught in boot camp by our DIs and by other trainers during advanced training after boot camp, especially in hand-to-hand combat. It works.

Did we have any "fun" at Parris Island? Surely you jest. "Fun at Parris Island?" Not hardly. If we cracked a smile, we hoped to god the DI or some other NCO didn't notice. Church was offered, but I don't recall anyone going. I never did, but we could go if we insisted. (Who was gonna do that at Parris Island?) The last day after graduation, when the DI said, "Dismissed and good luck", was the only "fun" I remember at boot camp. When I completed boot camp, I knew I was a Marine. (I would be an even better one later--a lot better.) We were like honored guests that last day. We were given a certificate, a picture of our platoon, and I was promoted to PFC.

For me personally, the long hikes with full field packs and learning all of the general orders had been the hardest thing about boot camp. When it was over, I had grown up quite a bit. I knew how to use weapons if I had to, and I knew how to look sharp.

I went home on boot leave for 20 days. I just hung around my family and wore my uniform some. All commented that I looked good. When leave was over I went back to Parris Island and was three hours late getting back because I missed the bus in Beaufort and had to hitch hike. I was lucky. They let me go free. From Parris Island I was sent to Treasure Island, California by troop train. The train stopped three times in different cities. We all got off and exercised about thirty minutes or so. I remember that El Paso was one of the stops.

In California, we boarded the USS Randall for a training camp in Hawaii. I think it was Camp Butler, but maybe not. The training was about the same as boot camp, only a lot more. It was all at the base. There was a lot of hand-to-hand, bayonet, grenade, and rifle training. For about a month in February or March of 1948 we trained on how to stay alive in combat. Our instructors were all Marines, but I can't remember any names. We watched training films and learned by field work. Real ammo was used in the field training. The biggest challenge of this infantry training for me was the obstacle course walls and crawling under barbed wire and live machine gun fire. We had no cold weather training. If we had, it might have helped some more stay alive in Korea.

We went to Honolulu once on liberty. We all hit the bars, even though most of us could not legally drink alcohol because we were too young. When the training in Japan was completed, we boarded ship for Tsingtao, China, with stops at Guam, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

We arrived in Tsingtao on 11 March 1948 and departed 2 June 1949. During that time period we mostly had guard and shore patrol duties. We were in China for the same reason we were in Japan, Europe, and lots of other countries. We had people and equipment to protect. I was young and did not ask why--only how and when. We were also there to release Nationalist troops to fight against Mao's Communist armies.

I thought the people of China were nice enough. They were like all the other people in countries where Americans were stationed. They wanted our money and a ticket to the States. Some of the food in town didn't taste bad, but we never knew what we were eating, and most of the time we didn't care--if you know what I mean. That rice beer was pretty potent.

When we boarded the USS St. Paul in June of 1949 to leave China, we could hear the artillery of Mao's army in the distance. I don't know exactly why we left, but if we had not, I guess we would have been permanent guests of Chairman Mao. After a month at sea while the Navy played war games, we docked at Long Beach, California and rode busses from there to Camp Pendleton. I stayed there for about ten months, pulling guard duty at various places on base, including the brig. I was also assigned duty as bartender at the Base Hostess House for a short time.

When the Korean War broke out, we began training hard in preparation for overseas duty there. General MacArthur asked for a Marine Division to make the Inchon landing, cut the enemy supply lines to Pusan, and recapture Seoul. That was us, the First Marine Division. We made the General look invincible, which he was. We were assigned to our company, battalion and regiment while at Camp Pendleton. I was assigned to How Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment.

I had learned a little about the "Land of the Morning Calm" while in China. I knew that it was cold as hell in the winter, and was rain and mud in the summer. I really had very little interest in Korea until they told us we were on our way there. Yes, we wanted to go to war. We were young and stupid then, and being Marines we thought we were invincible. We quickly learned otherwise when we went ashore at Inchon and found out that bullets fly both ways.

We were too busy training to follow the news about what was happening in Korea. (We were going to get all the war news we could handle soon enough.) They were in a hurry to get us trained and issue certain gear to us. My parents and close friends didn't know that I was going off to a war. We didn't know for sure ourselves until we were almost to Japan. We all thought that the war would be settled shortly after we got there. Why shouldn't we think that? All the top brass thought that.

As to personal preparations I made to leave for overseas duty, I had a girlfriend who belonged to someone else, so leaving her was not a big problem. I had nothing to store, and there were no leaves home to say goodbye unless someone happened to live near Pendleton. Most of us did not even call home because we did not know what to tell our families.

We left for Korea on the USS Bayfield. Once we got outside of Inchon, we stayed aboard for what seemed an eternity while naval gunfire supposedly softened up the enemy. Then we went over the side, down the nets into landing craft, and began circling for what seemed like another eternity before finally heading for shore. Our platoon leader briefed us to keep our heads down inside the landing craft, and that if the boat could not get all the way up on the beach we were to roll over the side into the water and make our way to the beach as soon as possible.

Other ships in the vicinity of Inchon were troop ships, LSTs, cruisers, and the Mighty Mo (Missouri), which was hurling its 2,000 pound shells twenty miles inland. From our ship I could see maybe 15 or 20 ships but believe me, we were not counting. We could hear the sounds of naval guns blasting, small arms, mortar, artillery fire coming at us, motors running, and people yelling. Overhead there were USMC Corsairs, Navy planes from carriers, and maybe even US Air Force planes from Japan, I'm not sure.

A few of us dropped some gear--a helmet, a rifle or two--as we climbed down the side of the ship. If I remember right, we were in the second wave. I think we landed about 2 or 3 p.m. on a cloudy afternoon. The tide was out and when we went ashore we had to use ladders (built aboard ships) to get over the wall. It was really rough going. We helped some up the ladder and over the wall upon reaching the shore. It was hard to hear orders. It seems to me that when we got over the wall, we were looking down on the roof of the houses so close together it looked like one big roof. Marines already had some POWs and there were a few dead enemy laying around. The smells were the same as in China.

Luckily resistance was fairly light, consisting of some small arms fire. The first wave or waves took out most of the heavy stuff, but there were a few casualties after we got ashore, mostly from snipers. I remember three North Korean soldiers trying to get through our lines with some refugees. We caught them and turned them over to our H&S company. I thought it would be fun killing gooks. I soon found out that it worked both ways. We all worked hard to stay alive.

I mostly played follow-the-leader once we got ashore. I was armed with a .30 caliber carbine. When the gunner set up the gun, I took ammo to it, fell back, and used my carbine to make some noise. I was the first ammo carrier of four, next in line for assistant gunner. I was as green as they come, but had no particular problem until the day after the invasion when we were pinned down in an open field and I froze--but not for long. I was an ammo carrier for a .30 caliber machine gun and when they called for more ammo, I thawed out quickly. War was a hell of a lot more than I could ever have dreamed of--hot lead zipping by my head, shells, bombs, grenades, all at the same time--and not knowing where they were. It was soon after we left Inchon that I saw the first dead Marine. I knew this was real, and I knew that could be me lying there.

We began moving toward Seoul, with the occasional firefight along the way. The closer we got, the stiffer the resistance. We were ambushed a couple of times and had to leave the road to rout them out. The fighting was just about all daytime. It was real intense at the start, then died down to just a few shots a minute or so. These fights rarely lasted more than an hour. I remember that once we were pinned down in a clearing with huge rocks on two sides, from which the enemy was firing. During that fight, I witnessed the heroic actions of our Navy corpsman, who repeatedly exposed himself to the hail of bullets to get wounded out of the open and treat them.

The gunner of our gun was killed. The assistant took his place and I took his. We lost three or four killed and some wounded on the trip to Seoul. I cannot remember the names of these casualties, but I do remember riding in trucks and on top of tanks off and on between hot spots. I don't recall Kimpo. I know that some of our troops took it and, if I remember correctly, it was not much of a fight. There were a lot of refugees and civilians in the area, but I don't recall them moving much. Guerilla activity was mostly hit and run, but they couldn't hide for long.

I don't recall any refugees or civilians at Seoul. There were MPs all over and the enemy had blown the bridge across the Han River. Our engineers built a pontoon bridge across it. We had support from the air and tank support on the ground. Like all others, I was scared (without our sergeants, we might have ran away--who knows), but we got the job done. There were heavy pockets of resistance, continuous sniper fire, booby traps everywhere, and house-to-house fighting in Seoul. The fighting was mostly in daytime, but at night also. We were assigned certain streets to clear out the enemy. We found them on top, in, and around buildings. The house-to-house fighting was new and scary, but my sergeant was a hero. He exposed himself to draw enemy fire so we could cut them down. Every outfit took prisoners that simply came out of hiding and lay down their weapons.

Once we cleared some caves of North Koreans. Kids came out first with their hands up. All of a sudden the kids fell to the ground. They had burp guns strapped to their backs. The men behind them opened up on us, killing at least one of ours and wounding three others before we could react. War is hell.

In two weeks we had secured Kimpo and Seoul and were chasing the reds to the 38th. Between Inchon and the 38th, there were hills, rocks, trees, rice paddies, and apple orchards. We could find cover when we needed to. Foxholes were the norm for us but we were usually not in place long enough at this time to dig them. We had some wounded, but I don't think any were killed in Seoul proper. There may have been. All of us had close calls. I was lucky not to be wounded. After the fighting ended in Seoul, it looked like London after the blitz. We Marines were chasing the enemy north when General MacArthur returned Seoul to Syngman Rhee. On 29 September we were above Seoul in hot pursuit. I think that is when we got orders to break off the hunt and return to Inchon. There we sat and waited for orders to board ship.

We lowly peons didn't know it at the time, but we were heading to Wonsan, North Korea, and on to the biggest fight for survival in military history. The epic battle of the Chosin Reservoir was about a month ahead, where hundreds of thousands of Chinese soldiers had orders to annihilate the 1st Marine Division to the last man. This was confirmed by prisoners. It seems Mao grossly underestimated the fighting ability and survival determination of United States Marines. We, the First Marine Division, were surrounded by ten Chinese divisions. We completely destroyed seven of them and badly crippled the other three. More Medals of Honor were awarded for the Battle of Chosin than for any other single battle in American military history.

Normally the trip from Inchon to Wonsan harbor would have taken about four days. But because of mine sweeping of Wonsan harbor, it took a week or more. I was on the troop transport USS Bayfield, I think. I cannot recall the features of the ship but I remember that our only contact with the ship's crew was at chow time. (The Navy always had good food. We ate steak and pork with all the trimmings while onboard.) There were close to 200 ships in the convoy to Wonsan. I don't know the types of ships since I was not Navy, but I do know there were an awful lot of LST types, troop carriers, and cargo vessels.

The only duty I had on the ship was to keep my personal area and my weapons clean. We read when we could find something to read. We also played cards and wrote letters. I remember that a couple of ship's crew played guitars and there was some singing with a few Marines joining in. There was some training en route, too, but mostly just oral lessons from our leaders. Again, we did a lot of weapons cleaning. We were also briefed a lot those last two days.

We didn't think much of their skills (often we had to retake areas they had taken and lost), but the South Korean Marines had secured Wonsan before we arrived. South Korean ROK forces had secured Wonsan on 11 October and on 24 October, Bob Hope and Marilyn Maxwell put on a USO show while we yo-yoed up and down the coast waiting for the mines to be cleared. We didn't land at Wonsan anyway. We landed on Kalma Peninsula on 26 October 1950. I can't remember anything about that first night after we landed. I know there was not any combat fighting that night.

The weather was fine in September in South Korea. North Korea in November and December was another story. It began to get a lot colder and we were issued parkas and heavy socks. Before the Chosin Reservoir campaign was over, I was so involved with staying alive, I hardly noticed the temperature. It was numbing, as low as 40 to 50 degrees below with wind chill factor of minus-70. The snow was wet and knee deep off the road.

Once we landed, we mostly walked into the reservoir area. There was very little truck or tank riding. During the battle of Sudong, Lieutenant Reem was giving us orders on placing our machine guns when a grenade landed in our circle. Without any hesitation, Reem fell on the grenade, taking the full blast in his stomach, saving us and later being awarded the Medal of Honor. There were others I heard about who were heroes during those battles on our way north. As we traveled up to the reservoir area, there were civilians heading south, and this slowed our progress because they had to be checked to determine who they were.

H-3-7 spearheaded the drive north out of Yudam-ni. That was as far north as anyone got as far as I know. There was no Marine regiment further north than our unit--none, zip, nada. Enemy resistance was light along the way as we traveled north, but then changed to heavy as the Chinese entered the war. As soon as we took a couple of them prisoner, we found out that there were many divisions of them ahead of us. My outfit, the 7th Regiment, 1st Marine Division under Col. Homer Litzenberg, was the first UN outfit to defeat the Chinese in battle after they entered Korea. We were under fire off and on all the way to Chosin and beyond.

Some of us learned quickly how to fight for real with a bayonet when our unit (H-3-7) was overrun by thousands of Chinese on Hill 1403 northwest of Yudam-ni in the Chosin Reservoir area on the night of November 27, 1950. It was nighttime when they came at us blowing bugles and whistles and beating on drums. I guess they thought they would scare us off the hill. They wore grey quilted outfits, and were armed with rifles, machine guns, pistols, and plenty of grenades. They were a lot better fighters than the Koreans. We stacked their bodies up like cordwood with our machine guns and grenades. Still they came. We were fighting hand-to-hand before they were stopped by our artillery. It was the worst experience of my life.

The whole experience in the Chosin Reservoir was all tragic. One would have to have been there to fully understand what it was really like. There is no way to explain what went on there. When I try to explain the details, nobody believes me. They think I am exaggerating. It was sort of like Custer's Last Stand--quick and deadly.

On the night of November 27, I became gunner and my personal weapon changed from the M-1 to a .45. Two Chinese divisions tried to destroy two Marine regiments that night. When my company was attacked, the reds surrounded us. The fighting was very intense with heavy losses on both sides. We repelled the first attack, but not the second. We were knocked off of Hill 1403 and ordered to pull back in the early morning of November 28. We were then ordered to retake it. We did, but at a heavy cost. We lost just about all of our officers and NCOs on Hill 1403. One guy shot his own finger off to get out of the fight, but lost so much blood he froze to death before he could be carried off the hill.

The fighting at Chosin was so terribly unbelievable that all we went through prior to that seems like a picnic. Nobody was supposed to get out of there alive. If not for the planning skills of our commander, Gen. Oliver P. Smith, we all would have perished. Anyone who was trapped up there will agree with that. I was afraid, but I just followed the instructions of my leaders, kept my eyes and ears open, and prayed a lot. I got through it all with just a few scratches and frostbitten feet and hands. We PFCs saw very little of the higher officers. I remember Captain Cooke and Lieutenant Newton in name only. I know Cooke was killed at Chosin. Most of our NCOs were out of World War II and the orders they gave us probably saved our lives. Most of our officers and NCOs were killed at the Chosin Reservoir because if they were wounded, they refused to quit. From my viewpoint, their leadership was excellent. Most of the ones I knew were real Marine leaders. They had to constantly expose themselves to enemy fire to make sure we were in our position. Some of them were awarded medals for their courage, including the Medal of Honor.

The cold affected our weapons in that the working parts would freeze together if not used every few minutes. The vehicles were left running so they did not freeze. Even the gas froze in the lines if not kept running. Our food was in cans and was frozen solid. We had hardly any time to eat anyway, but when we did we had to thaw a can inside of our clothes next to our body and under our arms if we ate any. My taste was okay, but there was generally nothing to taste. I could hear okay, but I never put the hood up on my parka. It covered my ears and all I could hear was it rubbing on my ears. I doubt if I could have heard a tank roar up behind me with that hood up. I could smell okay. Those gooks smelled like garlic.

My fingers were so cold I had to pull the trigger rather than squeeze. Since I had no feeling in my fingers, I had to fumble to get a belt of ammo locked into my machine gun. My feet and toes were dead. My face, ears, feet, and hands were frozen. (I now draw disability for frostbite.) I can't remember relieving myself. I guess it was because water and food froze. Probably the weather slowed my ability to think quickly, but then everyone else was in the same fix. I saw some guys pull the boots off their feet and some of the toes stayed in the boot. Before we got to Chosin, standing around a roaring fire, someone yelled that boots were on fire. Some said, "I hope it's mine!"

Occasionally there were short periods of time in a warming tent, but not if we were on the front line. Guys who griped the most about freezing spent more time in there than anyone else. Never did I stay in one long enough to thaw anything, including a can of food. The deep snow was real hard to get through. It wasn't the terrain so much as it was the weather that affected our ability to fight and defend. There was one little icy, winding, two-rut mountain road in the Chosin Reservoir area. There were mountains on one side and a drop-off cliff on the other, but we managed somehow.

Going into Chosin, H-3-7 had been the spearhead. We were the rear guard coming out. I had to set my gun up untold number of times to keep the chinks out of small arms range of the convoy. Sometimes I fired to the sides as our flank guards flushed Chinese out of pockets and they came running toward us. It was the same all the way to the sea. A couple of times I took my guns on the flank, up in the hills, when they encountered large groups of enemy. We were on flank a couple of times and it was real rough. Nobody wanted flank duty, but being Marines, who was going to disobey?

We received air support. Sniper fire was a continuous thing and so was the hit-and-run guerilla tactics of the Chinese. We were pinned down a couple of times until our fly boys could napalm the bastards and release us to mop them up. Without those heroes we may not have made our way out of there. Lots of times we prayed for the weather to clear so they could come diving in. My baseball hero, Ted Williams, was in Korea in 1952. He was one of those heroes--a Marine. Supplies were airlifted to us as we moved southward. I think we got most of what was dropped to us: ammo, food, and lots of big tootsie rolls, frozen solid. We had to fight to get some of the dropped items, but it was worth it.

I don't think there were any tanks close to us except when we were on the road coming out. They were real useful when they swung that big gun onto a nest of the enemy and blew them to hell. Numerous roadblocks were encountered, but they were cleared quickly with grenades, satchel charges, and/or heavy equipment like trucks, tanks, or bulldozers.

Marines have always brought their wounded and dead with them, and we did at the Chosin Reservoir. (A lot of Army walking wounded came into our ranks from the three Army battalions to our east that broke up and scattered to the winds when their leaders fell.) Our dead were piled in canvas covered trucks, and in some cases the wounded sat on top of the bodies. Corpsmen went from vehicle to vehicle to treat the wounded. I lost buddies all over Korea, killed and wounded. In some cases, like Chosin, I don't know to this day what happened to some of them. They just weren't there anymore when the battles ended. I witnessed the burial at Koto-ri, when a bulldozer scooped out a long, deep trench and dump trucks backed up to it. The frozen bodies of dead Marines were dumped in and the dozer pushed the dirt over them.

When we broke out of the Reservoir and arrived at Hungnam, there were photographers everywhere, but I remember no welcome, unless it happened before my company got there. We again boarded ship for Pusan, South Korea. We were all proud of our part in the operation. The whole world had written us off as a lost legion, yet we turned the tables on our would-be annihilators and almost annihilated them. Time magazine said ours was a battle unparalleled in United States military history. It had some aspects of Bataan, some of Anzio, some of Dunkirk, some of Valley Forge, and some of the Retreat of the 10,000 (401-400 B.C.).

It had to be God's will that I came out of that frozen hell. Others were dropping like flies all around me. I could hear and feel a little wind from the bullets and shrapnel whizzing around me, yet they missed except for a couple of grazes. Twice I was grazed on one arm and frostbitten hands and feet. I will always wonder how and why I got out of Chosin when so many others did not.

I was on the hospital ship Repose off of Korea for a couple of weeks or more. Then I went to Yokosuka Naval Hospital in Japan until I was well enough to return to Korea. I only had a piece of shrapnel in my leg and a wound from a bullet graze to my arm, but while there they also found I had a bleeding ulcer. It was probably from all the Russian vodka I drank when I was in Tsingtao, China in 1948-49.

I returned to Korea and stayed there until May of 1951, but I cannot recall much that happened there after Chosin. I can't even remember my commanders' names after Chosin. The book Breakout by Martin Russ talks more about the Chosin battle than any one person ever could. I'm even mentioned in that book. Imagine that.

After I came back from Korea, I was withdrawn and talked only when I was talked to. Any sudden, loud noise did then, and still does, find me ducking and looking for a way out. I also "climbed the walls," so to speak. For a long time, I was shell-shocked. I trusted no one and kept to myself. I used to find the darkest corner in a bar and just sat there drinking beer, speaking to no one and always facing the door. Back then I could drink all the time and still not be drunk. No now. My baby sister Margie noticed the changes right away. I'm a hero of sorts in her eyes. I'm sure others noticed also but didn't say much. My family thought I was dead or a P.O.W. because of all the news here that told of the 1st Marine Division in a trap, surrounded by ten Chinese divisions, plus written off as a lost legion by Washington.

I was released from the Marine Corps on October 20, 1951, at Charleston Naval Base, South Carolina. I married Mary Rogers on November 18, 1952. At that time, I was a welder of 60 to 30,000 gallon-sized fuel oil tanks. Mary and I have now been married 50 years-plus, and we have children Jean Rice, Patricia Hicks, William Sports Jr., Vicky Richardson, and Janet Privette. We also have 12 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

In October of 1954 I tried to get back in the Marines but at that time the USMC could not enlist married lower ranks. They wanted to put me back in--the recruiter went so far as to suggest I divorce Mary, re-enlist, and then remarry her. I decided to go into the Air Force, remaining in until September of 1970.

After retiring from the Air Force, I returned to school and got an associate degree in criminal justice. Most of the students were younger than me. They talked all the time--in class and out. The Corps had taught me to shut up and listen. One learns more that way. I worked in law enforcement a few years before becoming a Weigh master for the State of South Carolina, weighing both trucks and trains. I held that job until November of 1991.

In my second retirement, I do some woodworking in my shop--mostly just what I feel like doing, when I feel like doing it. We travel to Sioux Falls, South Dakota to see William Jr. sometimes. He is retired from the Navy. We also go to Florida to see our "baby" Janet.

Do I think the United States should have sent troops to Korea in the first place back in 1950? Yes. North Korea had to be stopped or they would have kept going unopposed. There is no way of telling what they, with China's help, would have tried next. MacArthur knew what he was doing going north of the 38th parallel. If not for Truman and his politicians in Washington, he would have won big in Korea and possibly cleaned out China as well. As Patton said about Russia, "We will have to fight the sons of bitches anyway. Let's do it now while we are here." In my opinion, one of the most serious mistakes made by the United States in the Korean War was Truman firing MacArthur and not fighting to win as MacArthur wanted to do. At that time, all of the Marines felt that way.

I have no desire to revisit Korea. I'm sure it's a pretty country to visit, but I sure don't want to live there or even go back for a visit. Maybe that's because everybody tried to kill me on my first visit. I saw all I wanted of Korea at Chosin. I smelled enough human waste mixed with gun powder to last several lifetimes. I am content to know that South Korea is free--for a few years, anyway. The only reason that North Korea is held at bay is because the US still has troops stationed there. Our troops will probably have to remain there for the foreseeable future.

The Korean War is known as "the Forgotten War" because it was known as Truman's "police action." People back home probably thought we were pulling guard duty over there. It is also forgotten because so little is said about it in our history books. World War II veterans are treated with more respect and appreciation than Korean War veterans, but I don't hold that against the veterans. Theirs was a huge war. I had two older brothers in that one. Some people in this country still know nothing about what we were doing in Korea.

I hope this memoir will someday help give future generations an understanding that the Korean War was the first war by free world countries to stop the spread of Communism. We must try to stop it anytime and anywhere it tries to force its will on a free people. Otherwise, we (the USA) could be next on their list.

When I returned to the States, I wrote one letter to the mother of one of my buddies killed in Korea. I got a thankful reply. I haven't tried to find anyone I served with in Korea. In fact, I figure most of them were killed. Any time I looked for a familiar face at Chosin it was gone, and a new one was in its place. One of my fellow machine gunners, Robert P. Cameron of Chicago, found me. I was told that of 250 men in H-3-7, only 27 walked out of Chosin.

I have permanent disabilities associated with Korea. I have badly frostbitten hands and feet which worsen with age. My lungs were almost destroyed from breathing the frozen air night and day almost 24 hours a day for two weeks at Chosin. About a year ago both of my lungs collapsed, and I suffered a heart attack all at once. I was on life support for three days before I came back. I now get 40 percent disability--10 percent for each hand, as well as each foot. I got the disability fairly easy. I guess the VA decided seeing is believing.

I don't attend company/regiment reunions. They are all too far away. I did attend a mini reunion in Miami a few years ago. We got the key to the city from the mayor (but it didn't work!). Even after 16 years in the Air Force, my Marine training stays with me, both in looks and action. My hands are not in my pockets, my shoulders are back, my chest is out, and my gut is sucked in. Folks notice that, too. Most of that is now beginning to wilt with age. It is true once a Marine, always a Marine. Even though I retired from the Air Force, my thoughts and loyalties remained with the Corps. I have even asked for a Marine honor detail at my funeral because Marines are, by far, the sharpest.