"There were so many things that were really difficult. The heat. The cold. The death. Seeing dead people a lot. I did get hardened to that, but I couldn't harden myself to the weather elements like the monsoon$300-$400 rains. The living conditions that I was in were really terrible. I stop and think, "How did I exist doing that?"

- Bill Venlos

The transcribing and publishing of this memoir was made possible by a grant from the Illinois Humanities Council.

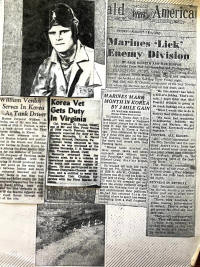

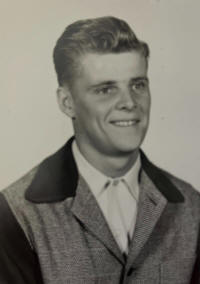

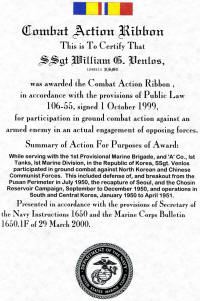

Bill Venlos was a Brigade/Chosin tanker in the Marine Corps during the Korean War. The following memoir is the result of an in-person interview that took place between Lynnita (Sommer) Brown and Mr. Venlos in November of 1999 in his home. Lynnita edited the transcription (by Tonda) into memoir form. A staff sergeant in Able Company's Tank Battalion during the war, Bill died November 21, 2003, at the age of 73.

My name is William George "Bill" Venlos of Galena, Illinois. I was born on January 17, 1930 in the northwest side of Chicago, Illinois and was raised there. My father was Peter Nicholas Venlos (1890-1965) and my mother was Marion Habada Venlos (1893-1976). I have two older brothers, Warren and Dale Peter Venlos.

My father was kind of a hard person to get any information from. Even as kids we didn't know much about his background, but I do know that my dad came over here from Greece as an immigrant in the early 1920s. His whole family was annihilated by the Turks during the Turkish-Grecian War that took place from 1919 to 1922. I guess my paternal grandfather was quite wealthy in Samara, which later became a Greek possession. He had olive groves and lemon orchards and used to export things to England. While on one of those trips he married an English woman. I never knew either of my paternal grandparents.

The name Venlos is an Americanized version of Venizelos, a name that goes back to one of the early premiers of Greece. My father was conscripted into the Turkish army during the Turkish-Grecian War after his family was killed. He was a very good athlete at the time and escaped the Turks by swimming to an English ship and asking for diplomatic immunity because his mother had been English. I still have the document signed in Greek and French that gave him permission to travel with immunity.

When my father immigrated to the United States he first worked for the railroad out west in Colorado. I can recall as a child seeing pictures of train wrecks. He was a foreman on a section crew that repaired tracks. I still have some of his old-time tables for the pay periods. He joined the Army before World War I, but came down with an illness and was discharged before the war began.

My mother had a Bohemian ancestry, but she was born in this country. Her father was from Austria. My grandparents on my mother's side were deceased before I was born. They were buried at the Bohemian National Cemetery, also on the north side of Chicago. Mother worked at Marshall Fields as a candy-dipper during the early 1920s. After she married my father, he opened a food store on the northern side of Chicago. To my understanding he had just opened two more when the Depression hit. He tried to make a go with the three, but lost all of them. He then tended bar in a little bar on the northern side of Harlem and Addison in Chicago that Al Capone used to patronize.

My earliest memory of my father was of him baking bread. He set up a route and I pulled the wagon as he went door-to-door selling bread. I was probably five years old at the time. Sometimes people paid him off with a chicken. I had a pet chicken that I named "Chicken". I used to kid my brother, "Oh sure, you had a dog--but I had a chicken." My father used to do most of the cooking. One Sunday he made chicken and rice, which we all liked. We were eating it and I didn't think much of it until suddenly I thought to myself, "Where's Chicken?" My brother said, "You're eating it." I had to get up. We always kidded about that.

I recall that my dad worked for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the Great Depression. That was a government work program created in response to the Depression. Because of his railroad experience he was hired as a time-keeper. I think he made about $30 a month, which was the pay rate back in those days.

My dad was one of the most patriotic persons that I can ever remember. I think the old immigrants were this type. He was a naturalized citizen. I still have his citizenship papers. He was very proud to be an American, and always flew the flag on all the holidays. One of my earliest remembrances of my dad was a Memorial Day when I was probably three or four years old. We were visiting the Bohemian cemetery where my material grandparents are buried, waiting for a parade to come. We were there quite early and it was very hot. I mean, it was really steaming. I remember waving a little hand-held flag waiting for the parade, but a little kid my age gets kind of edgy waiting. I put my arm down and dropped the flag on the ground. My father chastised me for letting the flag touch the ground. I still remember that to this day.

I didn't realize until later in life that my dad talked with an accent. I used to go down to Greek Town near Chicago with him when he went to pick up his Greek olives and Greek delicacies. The Greeks talked Greek to him, but he talked back to them in English. He didn't talk Greek unless he was in privacy with a neighbor who was Greek. One time I heard my dad haggling over prices with another Greek in a store. After leaving the store he said to me, "Billy, if you are ever going to do business with a Greek or a Jew, do it with a Jew. You're gonna get a better deal."

I went to grammar school at Saint Priscilla's, a Catholic school on the northern side of Chicago. After eight years I graduated from there and then went on to DuPaul Academy, which is a Catholic boys' high school, also on the north side of Chicago. The nuns beat on me at Saint Priscilla, and then the brothers and priests at DuPaul beat on me. You see, I was always in trouble for one thing or another. Not vandalism or anything--just always looking for trouble.

My father smoked Old Golds and then quit smoking shortly after that. My brother stole a pack of cigarettes from him and took them out to the guys to smoke. I smoked one, too. I think I had my first cigarette when I was about six years old. I didn't continue smoking. I was off and on.

When I was a kid in grammar school I used to sit by the window, look outside, and daydream. Geography was my best subject in school. I used to love to think of travelling to this and that. When I daydreamed, a nun would come up and grab my ear. I was always looking for some type of adventure. Because we were near railroad tracks, we kids were forever hopping on moving freights. When they still had the old steam engines we got in the viaduct that went over the main streets and hid in the girders. The engineer started wailing with the whistle because he knew we were hiding in those little crevices on the bridge. When he blew the steam we got all steamed up.

One time when I was 10 or 12 years old I was downtown Chicago. There was a trick store down on South State Street, which was kind of skid row. I picked up some itching powder that they used to have and some stink perfume and different things like that. I went to school with it one morning when I was in the 8th grade and put some of this down the back of the kid in front of me. He started itching and Sister Veronica said, "Can't you sit still, William?" He said, "Well, Venlos put something down my back." She asked me what I did and I showed her. She told me to take it down to Sister Priscilla, who was the principal. I went there and she said, "What did you do? Take everything out of your pocket and throw it in the garbage." I took the itching powder and the bottle of stink perfume and it broke when I threw it in there. Oh, that rotten egg smell! Well, I didn't dare go home and tell my parents, because then I would get it again from them. Corporal punishment was allowed back then, and I think it should be now in certain instances, too.

Music wasn't a prerequisite for graduation in a public school. A foreign language was needed to graduate from a private school, and so was music. I had Spanish, which I was terrible at. I decided to take a course in Greek to appease my father. It was more like ancient Greek and I didn't understand it. When I asked my dad, he said that it wasn't Greek--it was old-fashioned Greek.

I can remember that I was a kid when World War II started. Before that--I must have been nine years old--I still lived further from the city. My friend Walter and I used to collect war cards from the Chino-Japanese war instead of baseball cards. Quite a few other kids did, too. It was a hobby. We were kind of born into a war mentality even back before World War II. Then when we moved into Chicago there were lots of empty lots where we dug fox holes and played war games. The young girls that we hung around with were the nurses. That's how kids played when we were 9, 10, or 12 years old.

When the war began my dad started working in defense plants. He always wore his defense pins for production. My older brother Warren was probably six years older than my brother Dale and me. Warren joined the Marine Corps Reserve before World War II, but during training he broke an eardrum or something, so he was exempt for war action. Instead, he worked in an aircraft plant at Orchard Field in Chicago. A lot of people don't know that O'Hare International Airport is located on what was once part of the Douglas Aircraft Plant at Orchard Field. My brother Dale joined the Marines I think in 1944 just before the war. He was on Guam when the war ended, but he never saw any action. I was in school. I kind of remember buying little stamps for bonds or something like that during World War II. I can remember rationing and all that when I was in high school.

We later moved from out of far west Addison, Chicago to the end of the city a little further around Milwaukee and Addison. There was Schurz High School where most of my friends went. I can recall that a friend of mine and I worked at a German butcher shop. We used to deliver meat and we used to clean chickens. That was back when butcher shops had live poultry. I remember seeing German prisoners of war that worked at the Ford plant and passed by the butcher shop in busses. They were all waving and just so happy to be here. There was really no security on them. There was a Northwestern Railroad about two blocks behind us and one block the other way. We walked and played on the railroad tracks. There used to be a lot of military freight going through with tanks and trucks and all that, and we saw German and Italian prisoners of war on the trains, too.

Several fellas from the neighborhood fought in the war. One of them, Vandenburg, I think, was killed on Guadalcanal. We respected them. We saw them in their uniform when they came home in their greens and we thought, "Boy, these are tough-looking guys." I wanted to be like them. I think I just wanted to be the best. During World War II we were brought up on how heroic the Marines were in the Pacific islands. The divisions of Army soldiers overwhelmed the Germans during the war, but the Marines never outnumbered the Japanese. The Army just didn't do the job that the Marines did.

My last year of high school I transferred to Carl Schurz High School. I found out that I didn't have the credits that I needed to graduate with my class in 1947 because I didn't have music at my last school. I figured the heck with it. Getting to graduate with all my friends was why I had transferred to Schurz. That was really a mistake because not only was I not able to graduate with my friends, it was also a drain on my folks because there was tuition. At that time it was $350 a year or something to go to a school like Schurz, and that was a lot of money. I didn't think my folks could afford it and I wasn't that outstanding of a student, so I quit and joined the Marines.

I think it was in March of 1947 that my friend Frank Falbert and I went down and joined the Marine Corps Reserves just being formed on the Navy Pier in Chicago. I was worried about getting in because one of the fellows that I had gone to grammar school with had been turned down from the Marines. He was a big, strapping kid, but he was narrow, skinny and underweight. I was only about five foot four inches when I joined, but Marine Corps enlistment was down to about 72,000 personnel, so I guess they were taking anybody at the time. My mom wasn't concerned that I joined because she saw that I liked the Marines and it was peacetime.

It was a couple of weeks before we got our enlistment affairs in shape. I don't remember any officers there, but at that time there were maybe five of us brand-new boys just joining the Reserves. We didn't know anything. They gave us rifles to clean. One rifle was brand new and full of cosmoline [grease]. Oh, what a mess. It took us forever to clean the rifle. We used to go down to the Reserves once or twice a month. We got paid, but it wasn't much.

The Navy Pier back in those days was different than it is now. Nowadays it's an entertainment center. When I joined there was an old baby aircraft carrier there that the Navy used on old Lake Michigan to practice out of Glenview Naval Air Station. One of the old flat-tops was still there, but it was decommissioned. I believe it was the USS Wolverine, but am not sure. I guess they were scrapping it or something. They taught us about bulk heads, decks, and ladders that went on stairs, etc. We were just 17-year old kids, so we used to go up and monkey around on the ship.

About six or seven months after I joined the Reserves I joined the regular Marine Corps. I remember the day I took the oath when I joined the Marines. We were in an old building that had a big balcony around it. We stood on the balcony and an officer down below said, "Repeat after me." We swore allegiance to the United States government, the Marine Corps, the Naval service and all of that. They told us that we could go home and say our goodbyes because after that we wouldn't be home anymore. We were going to boot camp at Parris Island. They were nice to us in Chicago, but once we were sworn in they started--"Your butt is mine, and you'd better show up for that train or we're going to come and get you."

Frank and I were downtown and said, "Hell, we're staying downtown." We went to some bar on South State Street and got boozed up. We got down to the train station just in time to catch it before it left. There were about 14 of us from the Chicago area that were going to boot camp. They all had their parents down there hugging and kissing them goodbye. Frank and I came strolling in with a snoot full and got on the train. Late that night around 11 o'clock we all bunked down in old Pullman cars and we slept all night.

The next morning we picked up a bunch of recruits in Cleveland, Ohio. From there we transferred trains somewhere along the line and then we were on some military-type train. It stopped in Savannah, Georgia and we had a layover because of track problems or something. Everybody got out to see the town. At that time Savannah was just a sleepy little southern town with swamp all around. We had a good time that night. It was the last good time we would have for a while. When we got to Yemassee, South Carolina, we boarded an old wooden train that had wooden seats on it much like the trains they had in Korea. The train didn't go into Parris Island, so we got on a bus that took us there. From there on it was just like going into another world.

I remember my first day at boot camp. I think every Marine does. When we got off the bus there was screaming and yelling. Having been in the Reserves a little, we were kind of expecting this. I did anyway, but Frank was kind of giggling. We were in a state of shock because of the yelling and orders to do this and that. They beat on us with the swagger stick. We were a non-person when we fist got there. They wanted us to devoid ourselves of any other life before we joined. That was the Marine Corps' method of training.

The first thing they did was run us through the haircut thing. Oh man, they sheared us completely bald. Then they took our ID picture. They took away everything we had from civilian life, even pictures. We weren't even allowed to keep a wallet. All contraband had to be thrown away, and everything that was of value was tagged and shipped back to our folks. Everything was regimented by numbers and we had better do it right then. They issued clothes to us. We just walked through the line and they started throwing stuff at us. They piled it on, but nothing fit us. We got a shave kit and had to go through a physical and dental exam.

They ran us to chow while we were still in our civilian clothes. We saw other guys who had got there maybe just 24 hours before us. I thought, "Gee, look at them. Marines already." Some were from our neighborhood in Illinois, and some of them looked us up while we were at boot camp when they were getting out. They were maybe two weeks ahead of us, but they were real salty and senior to us. We had to say "Sir" to them and everything. These were guys we had grown up with, played baseball with and everything else. There were other platoons training, but we couldn't even talk to them. We were limited as to where we could go.

One of the first things they gave us when we got to boot camp was a scrub bucket. Everything loose went into the bucket--things like Barbasol shaving cream and razors. At the time I didn't have much of a beard at all, but we were supposed to shave every day whether we needed to or not. I was always getting caught for not shaving.

When I first got to Parris Island I had a pack of cigarettes. There were three cigarettes in it and I kept them rolled up in my pocket. We had to wash our clothes in a wash rack located behind the john.The DI caught me there a week later trying to sneak a cigarette. Oh boy, I got all kinds of hell. My punishment was a little bit of everything--pushups, digging a hole and putting sand in it, all kinds of things. They tried to think up something different all the time. After a while I think they may have even ran out of ideas.

Frank Falbert and I stayed together. We were in the same barracks and same platoon. Our main drill instructor (DI) was a southerner. We thought that he was the meanest son of a gun. We also had a boot corporal who had never been overseas. He was basically a pretty nice fellow, but the southerner would come in drunk from liberty in Savannah, and it was nothing for him to wake us up at 3 o'clock in the morning and make us wash the deck down with our tooth brushes. He used to call us the Chicago Gangsters. There were fourteen of us. Two of them received bad conduct discharges and another one got an undesirable discharge rather than a bad conduct discharge. The two that got bad conduct discharges had criminal records, but hadn't told the recruiters. I think one of them stole a car or something.

There was one other guy that was discharged during training. He was a World War II veteran who didn't tell anyone when he joined that he had a disability. He was from Hoopeston, Illinois. The day he left they gave him an old blue wool suit, a white shirt, a plain tie and a straw fedora. He couldn't go home in uniform and since they had taken everything civilian away from him when he arrived at Parris Island, that's what he wore. He looked like some real hick going home. He was a nice guy and would have made a good Marine, too. He was a little older than us--probably 24 years old or something like that.

One of the reasons why the DI called me a Chicago gangster was because I had to go to the dentist due to a bad tooth. I can remember lying in the dentist chair and the dentist drilling on my tooth doing what they call root canal nowadays. I don't recall having any Novocaine. Other shots didn't bother me, but I didn't go for shots in the mouth. The dentist was a Navy lieutenant who slapped me in the head saying, "That don't hurt. You're a Marine now." My face looked like I had been in a fight.

About six of us were standing in a row and they put us in front of a Navy psychiatrist. He had bushy hair and a bushy moustache. He started asking us questions like, "Do you like girls?" and some embarrassing questions. My buddy Frank was a wild kid. He was a big, big muscular kid and Frank started laughing like this: "Mmmmm mmmm...." So pretty soon I started: "Mmmmmm mmmm." All six of us were doubled over laughing, looking at this guy who was asking if we liked girls and that type of thing. When you're a 17-18 year old kid this stuff is funny. All of a sudden he said, "Get out of here." He chewed our DI out for bringing us in and because we acted like that. From that night on we were on the fecal roster all through boot camp.

I thought Frank was a tough kid. In fact, they got him to box. He was a platoon boxer and a heavyweight. I was a lightweight. Frank beat the heavyweight of the company that was going through boot camp at that time. I had two fights and both of them were TKO. I cut real easy above the eyes, so I lost the fights because they stopped them after I got cut. They didn't use head gear at that time. We had heavier gloves, but we didn't have any other protection other than that.

I thought back on my eight years of Catholic grammar school when I was hit by the nuns. They would grab us by the ears, slap us in the head, and hit us across our knuckles with rulers. The Franciscan nuns were pretty tough, although some were great like the ones who got out and played baseball. But they were tough and demanding. Then when I was in high school the priest and the brothers hit me. So boot camp was almost laughable to me and it wasn't that tough.

As I mentioned earlier, every day was regimented. Our day started at 5 o'clock in the morning. The lights went on and there was a lot of yelling and screaming from the DI's. At first Felder was one of the ones who could never get up. He was in the bunk above me and they had to roll him out. He just stood there laughing. He used to get me in a lot of trouble because of his attitude. I had no problem getting into my own trouble, but Frank was something else.

Once we were up we had to stand at attention waiting to hear whatever the DI wanted us to do at that particular minute. There was a lot of physical training, so calisthenics was one of the first things we did. It was very strenuous. We were in our skivvy shorts--you know, our underwear. Then we ran to the showers and the latrines and back. Maybe the DI would then want a field day at the barracks. Maybe we trained cleaning our rifle. Then we went to classes. We had the old Marine Corps manual. It was like our Bible in boot camp.

We had the option on Sundays to go to church services at any denomination that was there. It was a respite from training, otherwise we were back cleaning the barracks. They wanted us to be religious to have something to fall back on. The old saying, "There are no atheists in the fox hole" is basically true. I saw guys praying out loud in Korea.

We weren't in Quonset huts like most of the other recruits. We were in long, wooden barracks called PBY huts that were still left over from World War I. They were single-story buildings with no insulation whatsoever, and the boards were so warped there were spaces maybe three or four inches between each board. We could lie in our sacks and see outside. When it was the rainy season the rain came in and got everything wet. It got pretty cold at night. We had blankets, but when the rain came through it soaked our blankets and we had to air them out the next day. It was like camping out really. I think we were the last ones to use these particular barracks. They were located in the old 4th Battalion area of Parris Island way out near the swamp and beach.

I can recall one particular instance in the PBY hut that was funny. The huts had screen doors that opened in rather than out. It was the job of the two recruits living nearest the door to hold the door and let everybody run out. They were the last to go out. When the instructors told us to fall out we had to do it in so many seconds. One day the DI decided we weren't falling out fast enough, so he made us go out and come back in about 15 or 20 times. Back and forth. Back and forth. I finally said to one guy, "Don't hold the goddamn door this time." So when the DIs called out, "Fall out" again, we boomed right through the door and took the door with us. The DI found out that it was me that did this and he had me do cleaning for him. I had to spit-shine his shoes. I was like his houseboy. I had to come in on my knees, walk to him on my knees, and scrub the deck.

Pushups, running around the sandy parade field and doing laps were so-called punishment. I already mentioned the scrub bucket that was issued to us on the first day of boot camp. If we screwed up we had to walk around maybe for hours with that bucket over our head. The DI beat on it with his swagger stick saying, "Can you hear me? Hear me?" It was kind of ridiculous and more like hazing than anything. Although I don't approve of the hazing that was done in the Marine Corps, I realize that it was just to teach us discipline and respect for the people that give the orders.

By rights Felder and I should have been the platoon guidons because we had some prior military experience. One carried the platoon flag and the other was the right guard. They were like leaders of the platoon, but Felder and I never made it as guidons because we were always in trouble. A couple of other guys that had been in military school got the job because they were the "good boys."

Some of the recruits called me "Greek." One of them hated boot camp. One night he came over to me and said, "Come on, Greek. Let's go over the hill tonight. I didn't know it was going to be like this. I'm going home." I told him, "I ain't going any place. There's nothing out there." He took off and I never saw him again. I never regretting joining the Marine Corps when I was in boot camp. It was kind of a lark. They didn't really brainwash me like they do so many people because I had been through that with my parochial education. I'm not saying that the nuns or priests beat us bloody, but they clouted us.

When standing in line for chow we couldn't talk to anybody, even if we recognized somebody from our old neighborhood. There was no talking the first three or four weeks of boot camp. After that they eased up a bit and we could have some kind of conversation or we could whisper.

At Parris Island they had gnats called sand fleas. We called them piss ants. They were tiny and they were all over us eating at us, but when we were standing at attention we didn't dare flinch. We still had the old field scarves that we had to iron, so we chewed on them instead. Then if the DI caught us they got in our face and said, "Those are my gnats and you're trying to kill them. You can't wait until chow. You want to eat them." I couldn't help but laugh when he yelled at someone. Maybe I was a little hysterical. So many times it was funny to me, so I just chewed on that scarf. When we got into the mess hall we soaked our scarves wet.

I remember there was one big, heavy-set kid from Ohio that they kept threatening to throw out. They told him, "Oh, you're not going make it. You're too fat." But he wanted to be a Marine so bad. He used to say that he was a great eater. He said to me, "Greek, eat slow. You can eat a lot more." This was also the only time we got to sit down, so he and I were always the last two out of that damn mess hall. The last ones out of the mess hall always got the fecal detail--the shit roster I should say. I was a skinny little kid who probably weighed maybe 140 pounds when I went into boot camp. I got out weighing about 155-160 pounds and had probably grown an inch, too. The big, heavy-set kid lost a lot of weight because of the proper diet. He ate everything. I remember one time we had rice, but the rice started crawling because there were maggots in it. We were so hungry we ate it--really. We had to serve a week of mess duty, too. I can remember peeling potatoes with an old potato peeler. There was a big stack of potatoes because there were hundreds of recruits going through boot camp at that time.

Boot camp was 12 or 14 weeks when I was at Parris Island, but I think they shortened it during the Korean War. Our days were long and brutal and it seemed like they never ended. I think lights went out at 10 o'clock, but if the DI had a bug up his butt because he heard somebody whispering or something he would say, "Oh, you guys don't want to sleep." The lights went back on and we had a field day in the barracks again. In the morning we had to break our beds down. The DI came in and dropped a quarter on it. If it didn't bounce he might tear a hole in the mattress. If just one guy didn't make his bed up right we could all be punished for it. We had a couple of guys that goofed up all the time and couldn't keep up. The whole platoon suffered because of it. They just weren't physically fit. In fact, there was one kid who had a hard time walking. He had flat feet or something. He was always in trouble.

Each of us had a locker box. It was a big box with a lid on it and we kept all of our personal gear, underwear, and that type of thing in it. We had another locker that had a hook where we hung our clothes. Everything had to be placed in a prescribed manner. In the locker box our soap had to be here and our toothbrush had to be there. There was one kid who just never got it right. They made him carry that damn locker box around on his head all the time. That thing probably weighed 50 pounds with everything in it. He had to carry it around for hours.

The DI lived in the barracks with us, but he had a wall around his living space. There was a door, but the walls were open at the top. We could hear over the wall. When the DI called us we had to knock on the door and tell him who we were. There was a generally nice, quiet kid in our barracks who was always screwing up. The DI called him, the recruit knocked on his door, but the DI said, "I can't hear you. Who's that, some girl knocking? If you can't knock on that door, you can't come in." There was always ridicule. The DI made that quiet kid climb over the wall instead of coming through the door. When he dropped down he broke his ankle and that's the last time we saw him. The DI said that to me one time. "I can't hear you. I still can't hear you." So I knocked the panel out of the door. Ohhh, did he have a fit then! He said, "Get in here!" As I said, I was always getting into trouble for one thing or another.

I got letters from a girl back home. Her name was Loretta and she was crazy about me when I left. She didn't want me to join the Marines. She was an Italian girl with beautiful long hair. She sent me pictures of her sitting on a railing with her hair hanging down. My DI saw this and asked what I was going to do with them. He said that he liked the hair on her and he took the pictures. It wasn't that he confiscated them. He just said, "Oh, Boy. She's a pretty girl. Let me have those pictures." He said he was going to snow somebody else by saying that this was his girlfriend. I never did have any pictures because he took them. I don't think he should have been a DI. He just wasn't tough enough in all sincerity. We didn't give him any respect because he didn't deserve any. He was good at drilling and this and that. Back then we did a lot of what we called trooping and stomping. Drilling, formations, right flank, left flank, right obliques, left obliques, rear marching--just all sorts maybe hours at a time until we almost dropped. It was hot.

A lot of things I learned in boot camp were a lark to me, but I took my training seriously. A lot of guys didn't like the drilling and they cussed and moaned. I did, too. Frank never liked tearing down the M1. We had to do it on the spot. We had done that so much in the Reserves, cleaning all those old rifles. I used to clean his rifle and he spit-shined my shoes. One time I was cleaning his rifle and he hadn't put the bolt all the way back properly. It closed on me and pinched my leg. I still have a little scar as one of the remembrances. I found out later that Gen. Ray Davis was commanding officer of the 9th Infantry Battalion in Chicago, but I guess I had already gone regular by the time he arrived.

We were required to go to the rifle range for two weeks. The rifle range was a whole different area of Parris Island. There were Quonset huts and little palm trees. There were sidewalks, whereas we just had all sand. At first we learned to snap in with the rifle. There was no firing at all--just learning positions and how to adjust the belt in combat. We were not taught by our regular DI's on the rifle range. We were taught by rifle experts. By that time we were pretty well disciplined. Each of us had to qualify at the end of our rifle training. On the day of qualification it was a rainy day. They took turns taking us down to an area called the butts. We were standing in trenches that had back drops. In front of us were targets on pulleys. Someone pulled the pulley and we fired at the target. They then pulled the target back up after we fired so they could see what our firing score was. The day I fired I had a heck of a time because my sling--the buckle for my sitting position--came loose. I lost all the pressure of the strap and I almost didn't qualify. To my understanding, if we didn't qualify with the rifle we couldn't finish boot camp. They gave me time to stretch the rifle sling and I qualified as sharp shooter.

As boot camp continued we got to go to a movie once and we got to go to the PX after we came back from the rifle range. Most of our training was done by that time. At the beginning of boot camp we never got a good word. No 'job well done'. No pat on the back. Toward the end of our training the staff sergeant sometimes told us that we looked really good. There was competition among the platoons to see which one was the most outstanding 'honor platoon'. Esprit de Corps was learned in boot camp. Our platoon learned how to work as a unit and we worked really well together. We came in second place during the competition.

On graduation day the stands were full of people. We wore our uniforms and they presented our emblems to us. When we first got to Parris Island we were issued dungarees and dress greens. We had to wear greens when we went to church. During the graduation ceremony we wore our greens. Even though I was in good physical shape when I first got to boot camp because I had always played baseball, football, and everything else, I went in the Marine Corps as a weakling. As I mentioned earlier, I gained weight and height during boot camp. I came out thinking I could whip the world. I had learned discipline and how to work together. I had never had that feeling before. I don't think that even a kid that went to military school was as proud as those of us who succeeded in finishing boot camp. After graduation the DI's came up to us, shook our hand, and said they were sorry they had been so tough on us. We were Marines now, and they respected us.

Two of our DI's weren't really tough Marines. As I have already mentioned, I don't think they should have been DI's, but we came to respect the tough southern DI after we left boot camp. We respected him for the discipline he taught us and the respect we had for ourselves and others. We found out that he had been a World War II veteran in the Pacific and he had the ribbons to prove it. Just before our graduation from boot camp he came down with recurring Malaria and he was very ill. We respected him so much for the training we got from him and what he taught us about the Marines that a whole bunch of us went to see him in the hospital after graduation. At one time you probably had bosses that you didn't personally like, but you respected them for what they did and the position they were in. The DIs were good teachers.

After graduation we got a ten-day leave that included travel time, too. We took the Greyhound home, so that was a day we lost. We didn't fly like they do nowadays. Most of our time home was spent with family and our parents showing us off.

When leave was over we returned to Parris Island to get our orders. A lot of our guys went into the Marine Air Wing. We boarded a troop train and came across county down through Louisiana. I'm trying to remember how many were on the train. It was about a five-day trip. We slept in the seats and on the floor. There were no sleeping quarters on it because it was a military train with just a lot of seats.

We traveled through Louisiana and Oklahoma and then had a layover in Las Vegas due to a switching problem or something. We got off the train a little bit and most of us snuck off. One of our DIs from Parris Island was there and he was in charge of everything because the train was full of recruits that were going out to San Francisco to be shipped overseas. He tried to stop us from leaving the train, but we said, "Ahh, go to Hell." By that time he wasn't our DI anymore. He wasn't God anymore. We got out and had a couple of beers. At that time Las Vegas was just a little crossroad with a few little taverns and slot machines.

From there we went on up to San Francisco and went to Treasure Island. Treasure Island was a flat cement island actually next to another island called Yerba Buena Island. The island was originally built for the San Francisco World's Fair. Alcatraz was off in the distance about a mile away out in the bay. At that time the train used to run the Open Bay Bridge. (Not the Golden Gate Bridge, but the inner bridge further in the harbor.)

The last couple of weeks that Frank and I were in California, they had us chasing prisoners. There was a federal military prison on Yerba Buena island. It was a bad brig. At that time there wasn't the uniform military justice that the services go by these days. It was the old Rocks and Shoals. In those days if a prisoner escaped from you, you had to serve his time. So here we were at this bottom boot camp chasing them. These guys were bad. Some of them had committed murder. They were everything--Army, Navy, Marines. They were waiting for court-martial or already had been court-martialed. The brig warden was a green warrant officer and there was a master sergeant, too. Boy, those prisoners were mean son-of-a-guns. They were put on work duty to pick up paper on the roads on Yerba Buena Island, sweep the streets, and that kind of thing. Guards armed with shotguns had to take them out and then bring them in to the back of the brig. They had to strip down completely. The warrant officer and master sergeant had long rubber hose like billy clubs and they had to do a cavity search. The prisoners bent over and the guards would whack them with the hose. Oh man, I didn't want to go to the brig in that place. Frank and I had duty there for one week and we were so glad to get off that detail when they finally gave us our new orders. Frank was a big strapping boy, but he was more scared there than I was. He was tough, but he was an only child and inside he was kind of a mama's boy.

There were three Spanish-speaking guys that used to be in our tank in California--Cruze, Chavez, and I forget the other one. I used to be down in the driver seat singing God Bless America while they were chatting in Spanish. The Mexicans and people from South America used to illegally cross the border and follow a ridge line. When we were at Pendleton we used to see them walking along the ridgeline. Being the "Spanish-speaking tank", the Lieutenant sent us over there to corral the people because they were on government property. We had to call out to them, bring them down, and turn them over to immigration. I used to feel so sorry for those poor people. They had walked all the way from South America just to get to the United States and some of them hardly had any shoes on their feet. Chavez could talk to them. When we were sent to Guam I was in the bunk next to Chavez. When he woke up in the morning he said, "Que horas es?" I had taken Spanish in high school so I tried to answer him. I told him, "Ocho el", but the fact that I took Spanish in high school didn't really help me understand the Spanish-speaking guys on our crew.

Frank shipped out to Guam one week before I did. I was instructed to do a week of mess duty in California. After that I got onboard a ship to Hawaii. I had never been on a big ship before. We crossed the harbor from San Francisco and went over to Oakland to pick up supplies. The guys were seasick already. I saw guys lying in the well decks where the stairwells came down. They laid there for a week at a time and couldn't eat. They just laid there. I was never seasick. Just like what I had daydreamed about in grammar school, this was a big adventure for me.

I did a couple of days of mess duty on the ship and a few days of mess duty in Hawaii. We stayed in Hawaii about five days. At that time National City was the big liberty town. That's where all the sailors were. One thing I can honestly say is that I never had any problem with American sailors. I got along with them. You hear about bar fights, but I never did fight with sailors until years later when I got into a fight with an English sailor in San Diego.

We got to see the sights. I found out that the best way to see someplace was to get on a bus, ride to the end of the line, then start working my way back. I ended up in some really nice neighborhoods where people had never seen servicemen. I was treated great. That's how it always seemed to work in any major town I ever visited or went through. We had a free weekend once and we went down to Waikiki beach. We tried to swim one day, but the coral was so bad we got all caught up and couldn't even swim at Waikiki. We went to Pearl Harbor where we saw a lot of old battleships from World War Two. It was only a couple of years after the war and they hadn't salvaged everything yet. We could still see parts of some of the ships sticking up out of the water and oil floating around.

From there I got on the ship again and went to Guam. I served mess duty again a couple of days on the ship. Everybody got a turn. Once I got to Guam they put me in the infantry and right away I was on mess duty for a week. I was a professional mess man by that time. I knew all the shortcuts where to hide out and how to just get a mop and walk around like I was doing something.

Guam was a really pretty island. It had a beautiful climate, but sometimes it got hot. In fact, when we were on Guam we used to have what they called summer hours. We started at 6 o'clock in the morning, had chow at 1 o'clock, and then after that we were secure for the day because it was too hot to go down in the tank to work.

When I got to Guam a bunch of civilians in a construction battalion were working there. They went over on big contracts with big bonuses. They stayed so many months and then got a bonus. They worked for a private construction company under contract with the government. At the time there were no super highways on Guam. I understand that there are now super highways, big hotels and everything on Guam.

Frank ended up an engineer or something on Guam. When I got in tanks we were right near each other, so we used to go drinking at night. There was nothing to do on Guam but get drunk on 3.2 beer. With four guys at a card table, we could pile a pyramid of beer cans so high we couldn't see the guy across from us and still be sober enough to get back to the Quonset. After I got out of the Marine Corps I ran into a former Navy Chief who once had a bar in Apra harbor on Guam after he got out of the Navy. He married a civil service worker and stayed on Guam. He loved it over there.

They had movies every night on the base. There was an outdoor theater with welded benches made out of old World War II landing mats. Even when it started raining it didn't matter to anyone. They just kept sitting there. There were also some USO shows and some of them were hilarious. Everybody had a dog there, and there were also wild dogs. They would take off for a week and we wouldn't see them. Then they would come back and be sleeping at our feet on the bunk bed. One particular USO show was an Australian show that was kind of operatic. There was a soprano in the show singing high notes. Just like it was staged, two dogs came up from one side of the stage. One dog came and sat near her just looking at her while she sang, and then he started howling. Everybody started laughing and it broke up the show. It was really corny type humor, but the dog howling at the singer was hilarious.

At that time Chiang Kai-shek was the leader of the Republic of China. I was in an 81mm mortar border patrol when I first got to Guam with the 5th Marines. My job was to carry the base plate around, along with my own gear. Oh, it was hot in that jungle! There was a little PX on Guam and I saw a list asking for volunteers for tanks. They were sending 33 tank men to China to help get the Americans out of China before the communists took over. I thought tank duty would be a lot better than being in an 81mm patrol in the jungle, so I put my name on the list. Usually they started choosing alphabetically A, B, C, but for some reason they started at the bottom of the alphabet. Three of us had names at the second half of the alphabet. I don't know why they wanted to have people volunteer for tanks when they could have assigned people that were just arriving on Guam. Maybe it was because of our size. I know that some big guys were in tanks, but most of them were about my size with my build. I think that probably my selection for tanks really saved my life. There weren't too many guys in the Brigade that came back from Korea. I don't think there were more than five thousand that went over, and that included the Air Wing, support groups, and everything else. I once read that for every combat Army guy that was on the line there were twelve people supplying them. I don't think the Marine Corps had that many.

One of the volunteers was a guy named Holden. He had been in that brig on Yerba Buena. He did his time and then was shipped to Guam. He and I got full liberty one day and he bought a huge locker box made of cheap wood. It was actually bigger than a locker box. It was almost the size of a coffin. He and I got pretty boozed up and were sitting on the back of a liberty truck that picked us up after liberty in town. We were on a real bumpy road--Holden, his coffin, and I, when the truck hit a bump and the coffin fell off, breaking into a million pieces. He jumped off to try to collect the pieces. I was sitting there with a hangover, trying to sleep when the truck hit another bump. I flew out. I woke up the next morning in the ditch alongside the road, all beat up, dirty, and in a ripped uniform. I snuck back into camp. Nobody had even missed me.

There was no tank school. I was just assigned to a tank and it was "learn as you go." I immediately became part of a tank group on Guam. I was assigned as assistant driver on Joe Walsh's tank. He was my first commander and was one of the nicest guys. He was originally from Peoria, Illinois, and was a career Marine who had made it all through World War II. We trained on Sherman tanks. They were medium-sized tanks that had been used in the Pacific during World War II and we had never brought them back to the States. They stayed on Guam.

There was no driver's education for tanks. It was much like luck. As an assistant driver of a Marine Corps tank I was supposed to be able to know every position on a tank so I could replace somebody else if they were hit. I had to learn about the gun--how to load it, how to fire it. It was all done just by training. We had impact areas where we went out and fired, and everybody had a chance to fire.

We trained on what was called Brigade Hill. It was more of a plateau. Our tank park was maybe a mile away from where our Quonset huts were. A typhoon came through one day. We had our tanks in a tank park on the edge of a cliff at the plateau. We had covered them with tarps to keep the salt air off of them. We had secured the tanks, but one of them probably hadn't been locked in gear. When the typhoon came it blew that tank over the bluff. It rolled down and we lost it.

I guess we all had some problems learning how to drive a tank. I heard that in the old days a driver turned left or right based on someone else in the tank kicking him in the shoulder. We always had radios in the tank for communication. A Sherman tank was pretty hard to drive. It was nothing like driving a car--it was like driving a truck. Unlike the Pershing tanks that we later took to Korea, the Sherman had a clutch. Pershings had a shift, but not a clutch. To get the Sherman in gear I stood up, "double-clutched" it, and drove it standing up. Newer tanks were much easier to drive. After I got out of service I had a milk route for a while. I drove a Divco truck standing up so I could get in and out. It had a full back seat and was much like driving a tank.

When learning how to drive the Sherman the hatch was open. Needless to say, during combat while there was shooting going on, we were buttoned up. The tank had a periscope, but it was just hard to see with it so I always had the tendency to take my Marine Corps K-bar [knife] and stick it in the hatch to keep the hatch open. That's how I got some shrapnel in my face one time.

Sherman and Pershing tanks had five-man crews. There was a driver, assistant driver, tank commander, loader and gunner. The loader was on the left side of the turret and the gunner was on the right side under the tank commander who was sitting on a higher seat. It was very confining and I can see where some people just couldn't take that. I remember there was this one rookie who became claustrophobic during combat. He was my loader in Korea. He was a nice, quiet, nerd-type, but he was very frail. He got wore out lifting 90mm shells and loading them. There was a trick to loading. The loader had to jam the shells home, back away, and get his arm out of the way before it recoiled. It reminds me of when I was a kid, spotting pins in a bowling alley. I had to get out of the way when that ball was coming or the pins would get me.

There were three tank platoons on Guam, and one went to China.Altogether there were some 30 tanks on Guam--five to a platoon and two to a section. Then there was the platoon sergeant's or platoon leader's tank. The Sherman tanks on Guam had a 105 Howitzer. That was not a flat trajectory gun like the 90mm. The flat trajectory guns had more velocity. The Sherman tanks must have been brought back to the States after we left China because I don't see where they would have had that many tanks stateside. In Korea we used Pershing tanks. I trained on Guam for probably six to seven months.

We had to do maintenance on the tanks. They were pretty well broken in, but like most equipment, if we didn't run the tank there would be problems. The Sherman was old, but it was pretty dependable. During peacetime it was always boring having to clean the tanks. The inside of the tank was all painted white. I think that was for light when we were locked up because other than a little electric light there was no light down the driver's hatch. The inside of the tank was like a hospital, it was so clean. There was a lot of brass and spent ammunition shells.

I don't think I ever learned everything there was to learn about driving tanks. There was so much the drivers needed to know. Later on I was a tank platoon sergeant teaching kids about the tanks. I was constantly studying because the war was still going on. I wanted to send those kids over to Korea with as much training as I could give them.

I was on one of the tanks that went to China for about three weeks. The term "China Marines" usually refers to pre- or post-World War II Marines that were captured on Corregidor. I think they were from the old 4th Marine Regiment. We were the "new" China Marines.

The Chinese communists were coming down from the north and taking over all of China. At that time Chiang Kai-shek's government was basically a public government put in by the United States. He had been an ally to us during World War II, so he was more or less established as the generalissimo in China. Mao Tse-Tung was trying to introduce communism into China, which was ripe for it. In any history that I have read about China it was always controlled by warlords and different tribes. That's why there are so many different dialects.

The people were just dirt poor and everybody was trying to evacuate to get away from the communists that were coming in and slaughtering people. I guess a lot of them thought that they were going to be much like the Japanese during World War II. I guess Mao's people probably did do a lot of political killing. There was a lot of turmoil.

There was an American missionary town about twenty miles inland from where we were based, and our job was to keep the road to it open. We were basically a show of support. Our government wanted to make sure that all Americans that wanted to get out could get out of China. Later on a lot of Americans and missionaries were trapped in China and were prisoners of the Chinese. They went through hell during the days of communism.

We had a shuttle service type thing. Two tanks went up to the missionary town one day, had a layover overnight, and then returned to the base. On the way back to the base we met two tanks going up to the town. Along with the tanks there was a platoon of infantry just to keep the road open. Periodically there was some shooting at us from way up in the hills. They could have been communists, gang bangers, or maybe a peasant who didn't like the dust we were raising. Whoever they were they were such poor shots everybody kind of laughed at them. We were instructed not to fire back and we didn't. I don't know of anybody that was really wounded, but a couple of years before some Marines had been killed over there.

China stunk. The people there used to go around and pick up the garbage that had been tossed off the fantails of the ships. They were like street people going through garbage dumps behind a McDonalds in the States. They were starving.

We were in China only three weeks because the missionary town was secured by then. We were the last Marines to come out of China at that time. We went back to Guam for two or three months in late 1948, and then we went back to the States in April or May of 1949. I was then assigned to a flame thrower tank at Camp Del Mar as an assistant driver. I knew nothing about it, but I was trained by a tank commander who was a legendary World War II Marine. "Slope Plate MacDonald" was an old staff sergeant who had been on tanks in the South Pacific. By "old" I mean that he was maybe 26 years old or something and I was only 19 years old at that time. He was a gruff old guy who had been on tanks in the Pacific during World War II. The front of a tank has a slope plate. MacDonald was bald, so he got the name Slope Plate MacDonald. He was a character--and a hard drinker. He was one of those guys who always complained that we were not doing our jobs right, but he was kind of a sweetheart, too.

There was a long pier going out in the ocean at Oceanside back then. I think they rebuilt it later on, but it no longer went out that far. At the end of the original pier there was a bar where we could buy beer and sit around. When the surf came in the pier moved up and down. We could actually feel it moving as the surf waves broke against the pilings down below. The pier was probably two stories high off the water. One day I was walking on the beach up to the bar when all of a sudden there came an emergency vehicle. They could drive on the ferry like an ambulance. I said, "What the hell's going on?" MacDonald and another guy were all drunked up and they bet each other that they could jump off the pier and swim back to shore. MacDonald was big like an inner tube himself, but said he could beat the other guy. They both jumped in while the surf was pounding near the pilings and started swimming. One guy couldn't make it, so he grabbed hold of a ladder that was on the piling. MacDonald said he could make it, but all of the sudden he disappeared underneath the pier somewhere. Someone called rescue and they came down to search for him. By that time I had gotten there and got the story of what the hell happened. I thought, "Oh, jeez." I felt so bad. I started walking back to town. Across from the USO there was a new nightclub--the 501 Club or something like that. We walked in and there was MacDonald sitting at the bar soaking wet in khaki's. I couldn't believe it.

One of the tankers I served with had a 1939 Chrysler or something. It was one of those old gangster-type cars. He used to drive everybody around in his car. One day Bill Rayfield, Joe Welch, Ranky and Steve Duro were going up to Los Angeles. They each had a jug of wine sitting in the car. Somebody got drunk coming back and they hit a light pole. All of the electrical wires came down on it, but no one got hurt. One of the newspapers, the Los Angeles Times or Examiner--whichever one it was back then, had a picture of these Marines sitting on the curb with their jugs of wine, the car up against a power pole with the wires down, and sparks flying. The text under the picture said, "The Marines have landed and have the situation well at hand." That's the kind of characters those guys were.

Steve Duro was a big American Indian. He was a World war II veteran who never reached the rank of corporal because he always got busted for drinking. That old saying, "Indians can't handle fire water" was so true. After just two or three beers he was a falling-down drunken idiot. But that guy in combat was one of the bravest guys. He evacuated some of the wounded guys in Korea. More on him later.

At the time I was at Del Mar, a movie company started filming the Sands of Iwo Jima starring John Wayne. Our platoon was a Headquarters and Service platoon that had two flame tanks and two dozer tanks. Tank platoons were all in fours at that time. I was on MacDonald's tank and we were supposed to mix some napalm for one of the movie shots when the Marines were taking Suribachi. The tanks were down and some still pictures were taken with John Wayne in the background. We were mixing napalm and Slope Plate MacDonald said he knew how to do this. We mixed a batch of flammable gel in a big kettle. I remember pouring it in a big container with a big funnel. It was so thick it was almost like Jello. When we poured it in there it just ran out of the tube and down on the ground, but we finally got it right.

I think the Sands of Iwo Jima was filmed at Camp Del Mar and Camp Pendleton for 33 days in 1949 in late summer or early fall. The weather was hard to tell out in California. I usually go by weather, but California was always pretty hot or decent. During the movie most of our time was riding that detail because MacDonald's tank was in the movie. I got to meet John Wayne. He was just the nicest, cordial, congenial person you'd want to know. I not only shook hands with him, I have his autograph. We gave him a ride in the tank one day. I even went out drinking with him. John Agar, Shirley Temple's ex-husband, was a drunk. He came on the set drunk every day, and every day he was drunker. They had to reshoot his scenes over and over. Forrest Tucker was also in the movie--he was a nice man. There were a couple of other prominent movie stars whose names I don't remember.

Camp Del Mar is the base across 0101 that was on the beach. That's where our barracks were, but our tank park was out at Las Pulgas Canyon. There were tractor trailer bus-type things that took us to the tank park every morning for training and working on the tanks. The battle scenes were filmed on the beach right near our barracks, so we were down there every day watching them. They had the tanks standing by for whatever they wanted us to do. It was really nice duty and the rest of the company envied us.

My parents were proud of me and they watched the movie. There was one scene in the original movie that was cut out--I guess because of the length or something. The scene was of John Wayne critiquing five of us tankers who were standing in a circle. I was there wearing a jacket that said Zalinski on it because I had spilled oil or something on mine. At one time I had pictures of me with John Wayne, but every time one of my old girlfriends saw a picture of me with John they asked if they could have the picture. Like a dummy I gave it to them. I think they wanted it for John Wayne, not for me.

When the film came out they had a big premiere at Oceanside. There was a big party down in Hollywood for all the Marines that had participated in the filming. It was a nice get-together with a lot of starlets. It was summer, so we wore our khakis. That's when those of us in the Marine Corps still wore full khaki uniform, even the tie and our overseas hat. Our clothes were cotton and all starched and ironed. We had free time after hours, but we usually didn't have enough money to do much. When we went on liberty or when we sent our clothes to the laundry they came back like a board. We had to get our foot in the khakis and work our way down through it to open the legs because there was so much starch in it. We didn't dare sit down before an inspection. When we went on liberty and were out carousing all night, the next morning we looked like hell. So we took those khakis to the tailor to get them steam-pressed and all that starch came back again.

After the movie was completed the Marine Corps received four Pershing tanks. It was the M26 tank (M4 A3E 8). I think they got five of them on the east coast. At Camp Lejeune they had four. We had four on the west coast and for some reason I was put in the M26 towards the end. That was a new tank that had never seen any real action in World War II. It was produced during the end of World War II and the army had it. I knew one fellow that was on one of them in Europe towards the end of the war, but he had never seen any action. I guess they had them in mothballs while we were still using the old Shermans. The flame thrower tank that I trained on was a Sherman. The nomenclature for the Pershing was an M26. There were different technical things on the tanks. They were different in suspension. Some only had a 75mm gun, some had the 105, and some had the long 75 that could shoot a flat trajectory shot.

With the old Sherman tanks we put them in fourth gear, flew down the hill and kicked up mud. We kind of babied those tanks stateside because we had a lot of breakdowns. Once we got over that hill we ran the hell out of them and they seemed to run better. There was a lieutenant who had just come out of tank school in Fort Knox and he was supposed to be the expert. He wanted us to do everything by the book.

After we got the M26's we did a lot of training and firing on them. The range at Camp Pendleton had a flat trajectory and there was concern that shells might bounce off or skip beyond their range and accidentally do damage in one of those small towns outside of Camp Pendleton. Because of that concern and because we were kind of experimenting with our new M26's, we went down on the beach at San Onofre near San Clemente to fire 90mm shells over the ocean. The Coast Guard cleared a two or three mile field so we could fire rounds and then they took the velocity down. When we fired the gun there was a BOOM. It was phenomenal to watch the round go. We got a report back, "Cease fire!" The shells were going too far. They went out to where some private yachts were in the water near San Clementi island, so we had to cease fire. The gun on the M26 was terrific.

We had a platoon master sergeant named William Koontz. Almost everything I learned about the M26 I learned from ol' Willy, who was another Marine Corps legend. He was a holder of the Navy Cross from World War II. Willy later became a warrant officer and finished his 35-year Marine Corps career. He was just a real fatherly type. He always wore his head shaved or had it real short on the sides. He was a big, heavy man and sometimes we wondered how the heck he got in the turret in the tank. Although I already knew about tanks, this was a whole new tank, gun and everything. That man was a storyteller. We learned so much from him by just listening. When we went out to have a night field party we had a big bon fire and, like a bunch of Boy Scouts, we really just listened to him tell sea stories. We knew that most of them were true.

Willy Koontz told us things that a book couldn't tell us. The ground in California is hollow and the least little bit of rain could wash out certain spots. The water just stayed there. One particular time after a rain we had to drive our tanks down in a creek bed. Our tank was the first to go down and the tank got stuck in the mud. Koontz came over and said, "Wait. I'll show you something we did in World War II when something like this happened to our tank." He got a log, took the side fenders off the tank, and tied the log onto it. Another tank was in the front trying to pull us out while our tank was pushed from behind. We finally got it out by walking it out that way. Years later the editor of the Tanker Association newsletter had a picture of a tank without side fenders and asked me about it. I told him that it was my tank and I explained what had happened. He said that he had been trying to figure the picture out forever.

Shortly after the movie detail ended we got a new platoon leader. He was a baby-faced lieutenant who had been through World War II and had all of his ribbons (including the Navy Cross) on his uniform, but he looked as young as I did. He was one of the nicest lieutenants you would ever want to know. Quite a few of us had taken the test to make corporal. We had a formation in uniform one day and the names of the ones who had made corporal were called. Mine wasn't called and I wondered, "What in the heck did I do?" Before the lieutenant dismissed the formation he gave the corporal certificates out. In the service we were usually known by our last name unless our name was really close to somebody else's name. The lieutenant said, "Venlos, I want to see you in my office when this formation is over." I thought, "Holy Christ. What the hell did I do?" I knocked on the door of his office and when he told me to come in I stood at attention and said, "PFC Venlos reporting as the lieutenant requested." He held up a paper and said, "This is your corporal warrant. When you go to the PX and get a haircut you'll get this warrant." He was on me for getting a haircut because I was just never one of those that always shaved or got a haircut. So I went to the PX, got a haircut, and I guess made corporal for getting it. Ha ha.

The Pershing tanks in our platoon were constantly breaking down due to overheating, broken fan belts and things like that. The other tankers in the two platoons that still had the Sherman tanks used to pass us up and laugh. When we went out firing and we broke down, someone had to come out and retrieve our tank or tow it or fix something on it. There was always something going wrong. We found out later that the problem was we weren't running them enough. That was because of budget cuts. I think the same thing happened when the new Abrams tanks first came out. When they came out of Detroit they had passed all the tests, but once they got them in the field they were constantly breaking down due to filters and that sort of thing. Everyone had a lot of faith in the old Sherman tanks, so when the Korean War broke out nobody wanted to be out in the M26's.

My buddy Harold Waldoch used to pull liberty in Oceanside. It was close to the base and it was cheap. He and I used to go down there when we couldn't even afford to sit at the bar. There was a little ice cream cafe place there, and during the winter months we would go down to the bar. It was cold and nobody was swimming, but we just used to drink coffee and ice cream there. It was real Boston coffee, so we got cup after cup of it. We used to play the pinball machine that was there since we didn't have a heck of a lot of money. We were making something like $75 or $80 per month. Back in those days we got paid in cash on payday.

Waldoch wasn't in my outfit, but because our names began with "V" and "W", we were always one of the last ones to get paid. We were also the last ones to go on liberty. Being last in line for a payout, Harold and I used to either go down to Oceanside or go up to Los Angeles to see his cousins or uncle. Even without money we tried to pick up girls. Harold did meet a pretty redheaded girl and he got pretty serious about her. He didn't know that she really didn't want to get serious. She had a friend--kind of a blonde floozy, and they fixed me up with her. I was never much of a guy that could talk to women, so I never had that BS line. My wife will deny this, but I was always kind of bashful.

I was in Pendleton and we were still in training when the Korean War broke out. I immediately looked Korea up because of my interest in geography. In town we heard stories about the main side 5th Marines training. We weren't with the 5th Marines--our tank platoon was at Camp Del Mar. We were separate from them and not in the same barracks with them, but we sometimes trained with them doing tank problems with tank infantry.

I almost welcomed the Korean War because peacetime was so boring. There was constant drilling because most of the other Marines had not been in the Corps as long as the three years I had already served. When Harold Waldoch and I were on liberty, drinking in a bar and half in our cup, we asked ourselves why we had joined the Marine Corps in the first place. It was peacetime and we were so sick of training. Iused to make the statement that I wished a little banana war would start up someplace. Later when we were in Korea, Harold and I used to look each other up and we ran across each other quite a bit. But whenever tanks got hit or something he would worry. He was a radio operative and he worried about me. He told me, "You got what you prayed for. You're the one responsible for this damn war."

Waldoch was late meeting me in LA once, and when he arrived he said that there was a big brawl in our barracks. Infantry guys were getting so bored they started fights among themselves. They always said, "A mission Marine is a happy Marine." Waldoch said that two guys were duking it out, but he didn't know why. Fighting went on all the time among the infantry guys. Infantrymen were just a different breed of people. In town there were lots of fights among buddies. There was one platoon against another platoon in bar room brawls. In fact, they wanted to close the whole town of Oceanside down because the mayor was complaining that there were too many fights in town. General Graves Blanchard Erkstine, the commanding general of the Marine Corps at the time, said, "Yeah? Go ahead and do it and see how the town exists without the Marines." Another time they didn't want to allow the Marine dependents (kids) to go to the school in Oceanside. They weren't taxpayers in the town at that time. There was always animosity between most service towns and a big base. Most of them were there to make money off of the servicemen or the towns wouldn't be there in most cases. General Erkstine said they would have to close the town if no Marines were allowed in town.

At first we didn't pay much attention to it when the Korean War broke out, but then as it started heating up and the reports came back about the T34 tanks and how Seoul had fallen within a couple of days we thought, "What the heck's going on? Maybe we'll be called up." Everybody was kind of wishing that. Why would we wish that? It's a male thing, I think. It's to prove your manhood, I suppose. Or the adventure of it. You never think that you're the one that's not going to come back. You're invincible, especially the Marines.

Most of the guys pulled liberty in civilian clothes. One particular day I was walking on the beach down in Oceanside. This was a week or five days or something after the Korean War started. They announced over the loudspeaker PA system on the beach, "All Marines report back to your units immediately." All of a sudden a cheer went up. Everybody started evacuating the beach. It was almost emptied. Everybody was so glad that we were finally getting to do something. We thought it was another little banana war, but it was more than that.

We immediately started packing company equipment, ammunition and everything in big crates. We had to train other platoons to operate the M26s because a lot of them had never driven one until a couple of days before we loaded them on trains. A tank is a tank, but there was some difference to the driver in feeling the weight. The M26 was more maneuverable on hills than a Sherman. In a Sherman tank a driver could come off of a hill in fifth (high) gear. Let it fly and the tank was down. But with the Pershing M26, the highest gear to come down a hill was third gear. It was supposed to be put down in reverse and eased down. While I was in training earlier, I was grounded for thirty days because I had driven my tank down in third gear instead of putting it in low. At that time I was assistant police sarge for Dent, an Asiatic character. We were kind of close.

I remember going to main side and putting the tanks on flat train cars. I think there were 25 tanks, so we were two or three days doing this.Everybody was excited, but it was hot and we worked our butts off. I remember the day that we secured all the tanks. They loaded us on tractor trailer buses and drove us down through Oceanside. I remember a lot of people along the road cheering us and saying, "Come back." It was really heart-warming the way the people sent us off. It was like that almost all the way down to San Diego. We were on old Highway 101. It wasn't a super highway like it is now. We had to go through Del Mar and all those little towns.

When we got to San Diego we offloaded our Pershing tanks onto a landing ship dock (LSD). There were two tanks abreast of each other on the LSD. Two were in front of us. A landing ship tank (LST) is a ship that they could unload or load and go out to sea. The name of our LST was the Fort Marion. They flooded the inside of the well deck to make it lower so they could float smaller boats like landing craft mediums (LCMs) into it. Those usually held a couple of tanks. They were in the bow of the ship and could be driven off by pumping out the water.

This was in July of 1950. As we were getting out of the harbor and heading out to sea, we were up on deck as a band played the Marine Corps Hymn. Suddenly a loud speaker said, "Tankers report down to the well deck." A sailor had evidently left open some kind of valve and the water came in and flooded out some of the tanks. My tank was one of them, but it didn't have any damage to it. Two other tanks were lost completely (they wouldn't start) because salt water got into their engine and wires were destroyed. They were probably rehabbed later when they got to Pusan. We lost some ammunition, too. We had loaded all new ammunition called high velocity armor piercing (HVAP). It had a shell that had never been used during World War II. We didn't know what the capacity of the shell was because we had straight-loaded it. We had no high explosive (HE) ammunition and we had no white phosphorus (WP).

We sailed in a convoy reminiscent of World War II. I remember one day I went up on deck and looked around. I saw ships all around just as far as I could see. I don't know how many ships were in the convoy. I thought there was supposed to be something like 50 or 75. Maybe it was bigger. It was exciting. I thought, "Oh boy! This is really good!" About a third or maybe half of our outfit was made up of World War II guys. They had been through war and they had elected to stay in the service because they liked it. War was part of their job.

There was gambling on the ship, but I never did gamble much. When I first got to Guam I was the new kid in the neighborhood, so I didn't say anything when all the sergeants were gambling. They had pots of $300-$400, which was a lot of money back then. Some of them were pretty good gamblers. One guy sent home $15,000 to his wife in the two years he was on Guam. He had a stack of money order receipts. On the ship to Korea the guys who had money sat there for days on end gambling during almost the three weeks it took us to sail there. They paid someone to bring them a sandwich or coffee from chow and just played cards constantly.

I did a lot of reading. None of us were smart enough to think to bring enough reading material, but at that time Mickey Spillane authored the book, My Gun is Quick. There must have been 15 to 20 guys reading it at the same time, so they would look around after reading four or five pages saying, "Who's got page so and so?" That's how the book was passed around--in pages. We also had training in the tanks and in classes and there were calisthenics. If some guy goofed off they put him on duty chipping paint like the sailors did. I never had to do it, but I saw other Marines who were stuck doing that.

We brought the high velocity ammunition on our ship because it was fast to load and we had to get it over to Korea. Once we got there we offloaded that ammo and then loaded a mixture of what ammo we would need. We were supposed to stop off in Japan and reload everything to get it ready for an amphibious landing, but things in Korea were so bad at that time we never did get to Japan.

The day before we landed in Korea was August 1, 1950. I went up on the deck early that morning just after chow to have a cigarette. It was a beautiful, beautiful day. We were going through the southern Japanese islands and they were all green and beautiful. The air was even green. I rubbed my eyes because I thought I had green glasses on. Everything was calm. The author Joseph Wambaugh later wrote a book titled, The Blue Knight. He mentioned an old phenomena called a green mist. I guess they experience it once or twice in California. It is supposed to be an omen that if you ever experience it, nothing bad will ever happen to you. It really has come to pass for me. I still remember to this day how beautiful it was.