"I knew that if I joined the Corps and got a uniform like that, I'd get the pretty girls because they would think I was something special. I wanted to become a hero, too. I also guess I was a little patriotic and loved my country."

- Clarence Hagan Vittitoe

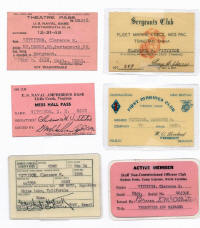

KWE Note: The following memoir is the result of a series of questions/answers transmitted between Hagan Vittitoe and Lynnita Brown on the internet during the months of July/August 2004. The photographs are courtesy of Hagan.

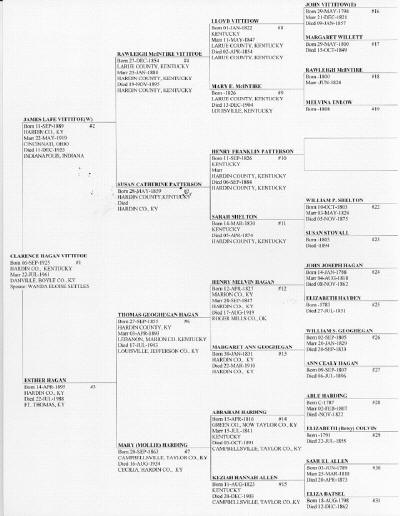

I was born Francis Hagan Vittitoe on September 6, 1925 in Cecilia, Hardin County, Kentucky, the third son of James Lafe and Esther Hagan Vittitoe. That is, I thought my name was Francis until I got my birth certificate in order to join the Marine Corps. At that time, I found out that my real name was Clarence Hagan Vittitoe. I have never been called either Francis or Clarence. When I was born, it seems my brother Lloyd Allen could not pronounce Hagan, so he called me Hagie. Therefore, all during my childhood, I was called by that nickname.

At the time of my birth, both of my parents worked at the Indiana State Hospital in Richmond, Indiana. There was no cash money to be made in or around Hardin County (or in Kentucky, for that matter), so they had to go to Indiana to make a living. My mother was a Practical Nurse. I'm not sure what Dad did, but I believe he was some kind of male nurse. I'm not sure just when they started working there, but it was before they were married--a few years before World War I (about 1915), I think. There were several people from Hardin County that went to work at the hospital. There was no money to be had in Hardin County at the time. The pay at Indiana State Hospital, although low, was better than nothing.

Although my parents lived in Indiana, Mom went home to Kentucky to have her children. My brothers were James Albert Vittitoe, born March 15, 1920 and Lloyd Allen Vittitoe, born August 25, 1923. Both of them were also born in Cecilia. While my parents worked in the hospital, my brothers lived with "Papaw" and "Mamaw" (our grandfather Thomas Geoghegan Hagan and grandmother, Mary (Mollie) Harding Hagan). After my birth, Jimmy and Lloyd Allen still stayed with Papaw and Mamaw, and I went with Mom and Dad to Indiana.

I remember very little of my early life, but have been told that I boarded with several different families for the next few years while living in Indiana. When I was about five years old, we went back to Kentucky, and all three of us boys went to live with an Aunt and Uncle. They were not really our Aunt and Uncle, but distant relatives of Dad's named Yates. I got some of our Vittitoe family information from Ina Yates Atcher. They lived around Rineyville or Vine Grove in Hardin County. I'm not sure just how long we stayed with them.

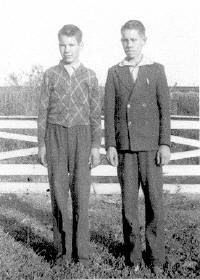

At the height of the Depression, I think around June of 1932, my two brothers and I were admitted to the "Kentucky Baptist Children's Home" in Glendale, Kentucky. This Home is now called "Glen Dale" and the name has been changed to "Kentucky Baptist Home for Children." There were about 100 boys and 100 girls living in the Home at the time, ages about one month to eighteen years of age. Our Dad was an invalid (due to epilepsy), and had been admitted to a hospital in New Castle, Indiana. Mom couldn't take care of us three children, so we were sent to the Baptist home. Jimmy was about twelve years old. Lloyd Allen was eight. I was six years old at the time.

At the height of the Depression, I think around June of 1932, my two brothers and I were admitted to the "Kentucky Baptist Children's Home" in Glendale, Kentucky. This Home is now called "Glen Dale" and the name has been changed to "Kentucky Baptist Home for Children." There were about 100 boys and 100 girls living in the Home at the time, ages about one month to eighteen years of age. Our Dad was an invalid (due to epilepsy), and had been admitted to a hospital in New Castle, Indiana. Mom couldn't take care of us three children, so we were sent to the Baptist home. Jimmy was about twelve years old. Lloyd Allen was eight. I was six years old at the time.

I don't remember too much about life at the Home. At the time, I didn't think it was too happy. But looking back, it was a pretty happy childhood. We had electric lights, central heat, indoor plumbing, and plenty of good wholesome food (beans, blackberries, bread and milk). This was more than most Southern Baptist children living in Kentucky could say at the time. This was during the Depression years of the 1930s.

Jimmy stayed there for about four years, and when he left the Home, he stayed with Mr. John Gardner, teacher and basketball coach at Glendale High School. (Boys had to leave after they turned 16 years of age. Girls could stay until they turned 18.) He played basketball for Glendale the next four years until the spring of 1940, when he graduated. Lloyd Allen and I stayed at the Home until about June 1941. At that time, Lloyd Allen got a job with Reynolds Jackson, a former resident of the Home, in Dover, Delaware. I went to live with Mom in Newport, Kentucky.

While a resident of the Home, I attended grade school at Glendale Consolidated High School in Glendale, Hardin County, Kentucky, but never actually went to high school. I was not a good student, and when I left the Home, I was in the 8th grade. I was not involved in any organized sports or the Boy Scouts while I was living at the Home.

When I went to live with Mom in Newport, I had to start the eighth grade over. I went to 4th Street School in Newport for only about eight months, starting in September of 1941 and leaving about April of 1942. I did not finish eighth grade, but left in mid-term. I later got the equivalent to a high school degree through the G.E.D., and got an associate degree from college after returning from the Korean War.

My older brother James joined the Marine Corps in March of 1941 before World War II started. He became a pilot in the South Pacific. He wrote a story about his experiences in World War II, and I have submitted it to the Korean War Educator in his honor. Click HERE to read his story. James stayed in the Corps until he retired in 1962 as a Captain. He died on July 25, 1994, in California. All three of us--Jimmy, Lloyd, and I, served in the Marine Corps while World War II was in progress.

After leaving school, I went to work for Western Union as a messenger. I worked in Cincinnati, Ohio at the Sycamore Street Office until about June of 1942. Then I went to work for Postal Telegraph as a messenger. I'm not sure why I changed companies, as I remember the pay was the same (0.30 per hour). Perhaps it was the uniform. Postal Telegraph did have a sharp uniform.

My other brother Lloyd served in the Marine Corps from August of 1942 until 1946. He was on Guadalcanal with the Second Division in 1942, got malaria, and was sent back to the States, then later returned to the Pacific and joined with the First Division to fight on Pelileiu and Okinawa. He went into North China with the First Division after the war. He stayed there until the spring of 1946, when he returned to the States. He became an over-the-road truck driver, retired about 1985, I think. He presently (2004) works on the Boone County Golf Course in Florence, Kentucky.

I joined the U.S. Marine Corps on September 10, 1942. I'm not really sure anymore why I joined, but I think it was because of my brother Jimmy. Jimmy has always been my hero – someone I've admired and looked up to all my life. Older brother, high school basketball star, Marine Corps officer, fighter pilot, and to top it off always got the prettiest girls. What's not to admire? He had joined the year before and came home in his "Dress Blue" uniform. I had also seen several movies with Marines in Dress Blues, and they showed that the Marines always got the pretty girl. I knew that if I joined the Corps and got a uniform like that, I'd get the pretty girls because they would think I was something special. I knew that if I had a uniform like that, I'd have to beat off the girls. (It would take me six years to get a uniform of Dress Blue.) I wanted to become a hero, too. I also guess I was a little patriotic and loved my country.

Mom was a little worried because she already had two sons in the Corps, but I begged her to let me join, so she finally signed the enlistment papers. My Father was still living, but I had not seen him since about 1934. I really never knew him, although he did not die until December 11, 1953. I was seventeen year olds when I enlisted. My buddy Richard Buchanan joined the Marine Corps at the same time I did. We were both 17 years old and wanted to get in before the war was over. About twenty of us boots who had joined the Corps were on the train. It took us to Parris Island, South Carolina.

We left Cincinnati in the morning of September 10 and arrived in Atlanta that evening. We spent the night in the Atlanta train station and I remember thinking at the time that General Sherman must have just left only a few days ago because the train station looked like a shed after Cincinnati Union Station. The next day, we took the train to Savannah, Georgia, then north to Yemassee, South Carolina. From there, the train backed up to Beaufort, South Carolina. In Beaufort, we boarded cattle trucks to be taken into paradise (Parris Island). As we entered, everyone (by the thousands) yelled to us that, "You'll be sorry"--even boots that had only been there a couple of days.

That first day, we received a lot of instructions. There was the issuance of gear, arrangements made for quarters, and a change in appearance. We were assigned to platoons and drill instructors. I was in Platoon Number 740, and my senior DI was Platoon Sgt. J.W. Hiott, who was later killed on Okinawa. My junior DIs were Pvt. T.K. McNerney, Jr. and C.C. Curtis. I never heard of either of them after I left boot camp. The senior DI was never around. He left it up to the Juniors to take care of us, and they did. It is the junior DIs whom I remember.

I don't recall how long boot camp was--it seemed like years. We learned in a hurry to obey anything and everything our DI told us to do. The DIs told us when to get up, when to eat, when to brush our teeth, when to go to the head, when and how to clean the barracks. Lights were on or off, depending on the mood of the DIs. This was war time, and there was no question about who was the boss. DIs made no mistakes, no errors. Their word was law and final. There was no one to appeal to. If the DI said it was wrong--it was wrong. Strict? Yes!

This was before the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). The UCMJ includes the rules and laws that Marines are governed by today. When I was a boot, the Marine Corps and Navy had the "Rocks and Shoals." Punishment was given out when a DI thought it was necessary--usually a hit across the pith helmet with a swagger stick. But that didn't happen often. It wasn't necessary--we obeyed him without question. There were no troublemakers--they would not have lasted through boot camp. For the most part, we came from a generation that obeyed orders. Remember, too, there was a war on. DIs did what they thought was necessary to turn us into Marines. They did a very good job of turning a bunch of boots into proud Marines--no easy job, I can assure you.

On sandy and hot Parris Island, we had no free time in boot camp. Instead, we had classroom and hands-on training. Our classroom was usually sitting in the sun while our DI sat in the shade and lectured us. Classrooms were anywhere the DIs decided we needed a lecture. They were usually held at odd hours and uncomfortable places.

We had to memorize the "Marine Corps Hymn" and our "Ten General Orders", as well as our own serial number and the serial number of our rifle. I still remember bits and pieces of the ten general orders, although I can't quote them in order now if asked to do so... (1) Stand my post in a military manner, keeping always on the alert and observing everything that takes place, sight or hearing...something like that. But most of all, we had to remember which was our right foot and which was our left foot. This was very important throughout life in the Corps.

There were 61 boots in my platoon. Richard Buchanan and I were in the same platoon, but after boot camp, I never saw Richard again and have no idea what happened to him. For the most part, we were all young and in good health. We had all came out of the depression era, and were in good physical health, so the calisthenics and hiking for twenty miles was not a great problem for us.

Food was good and plentiful, but if you took it, you had better eat it. For the most part, we were all poor people who hadn't been eating too well before boot camp. If anyone complained about the food, I'm sure the DI didn't hear him.

We all attended church services. I can remember when I was asked, "What religion are you?" I said that I was "Southern Baptist." I was told I had to be either Jewish, Catholic, or Protestant. Given those choices, I chose Protestant without really knowing what a Protestant was. I ended up with a "P" on my dog tags.

One of the most important aspects of boot camp was weapons training. We fired the rifle in late October at the rifle range in New River, North Carolina, which later became known as Camp Lejeune. We were required to "qualify" on the rifle in one of three categories: expert, sharpshooter, or marksman. Fear of the DI made you one of them. I believe in boot camp I was a sharpshooter. I know that all in our platoon qualified.

When it was time for graduation, I was as proud as anyone could be. Before we graduated, we couldn't wear the emblem of the Corps. Now we were real Marines. I think there was a certain pride just knowing you went through Marine Boot Camp and survived. It felt good and proud, and it still feels that way today. At the time, I was too young to appreciate just how much I owed to the Corps.

I did not go home after boot camp. Instead, I joined the First Barrage Balloon Squadron at Court House Bay at New River. They were already preparing to ship out. We stayed there only a few weeks, and then the squadron was transferred to Camp Elliott, California, just north of San Diego. We traveled there by troop train in late November. (This is when I started to understand just how large this country is.) We boarded the Dutch ship Boomfontain (sp?) to set sail on December 3, 1942 for the South Pacific.

The ship was a former Dutch Luxury Liner with a crew of Dutch and a few American sailors. I'm sure that the ship never carried that many people when it was a Luxury Liner and, yes, it was crowded. The passengers were all Marines, but I have no idea how many there were on the ship. The cargo was Marines with their equipment.

About all I remember about the trip was how boring it was. This was my first trip by ship. The largest ship that I had been on up to that time was the Island Queen on the Ohio River. I did not get sea sick, but a few Marines did for a short time only, and soon bounced back. There was no entertainment on the trip--this was a troop ship, not a pleasure cruise. There was no training. We just stayed out of the way of the sailors.

I remember the ceremony crossing the Equator. It seemed like a big deal at the time. As we crossed it, we were invited to kiss King Neptune's Belly (a fat Dutchmen's greasy belly), and be initiated into the mysteries of the deep. I'm not sure if I became a "shellback" or a "polliwog" or perhaps was one of these before the ceremony and became the other after this ceremony. After the ceremony, we became "old salts."

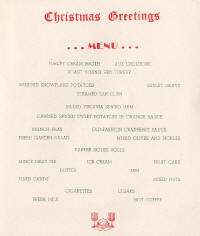

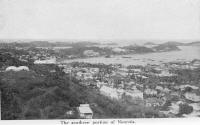

The trip took about twenty days. We arrived in Noumea, New Caledonia, on December 23, 1942, in time for Christmas. The island was located approximately 750 miles north-northeast of Brisbane, Australia, and about 1000 miles north-northwest of Auckland, New Zealand. It was very important to the Navy during the early days of the war. This was a French Island that had been used as a leper colony. In World War II, Noumea was an important naval base for the American fleet to replenish supplies and make small repairs.

The job of the 1st Barrage Balloon Squadron was to help protect the Noumea harbor. I don't remember my specific job, but I do remember that the squadron had twelve balloons and there were approximately eight to ten Marines to each balloons, I believe. They were set up around the harbor. Barrage balloons were large, egg-shaped windbags, filled with lighter than air helium. They were released to go up into the air about 500 to 800 feet (I'm guessing the distance). Each balloon had a wire about the size of a #2 pencil attached to it which stretched between the balloon and the ground. With 12 such balloons sent up around a harbor, a dive-bomber might not be able to get in to bomb the ships. If he got in, he wouldn't be able to get out again without running into one of the wires. Theory was that if we had balloons around the harbor, the Japanese pilots wouldn't try to dive-bomb the ships in the harbor. (You may remember that London was protected during the 1940-41 blitz by barrage balloons.) Only a few months after we got there, the Marine Corps felt that there was no longer a need for the balloons, and disbanded the squadron. The Japanese didn't have planes that could reach the harbor.

I stayed with the First Barrage Balloon Squadron until the summer of 1943, when I was transferred to the Guard Company, First Base Depot, also located on Noumea. My guard duties were to protect warehouses, fuel, ammunition, and all other supplies that Marines needed. I was with First Base Depot for about four months until the fall of 1943, when I was then transferred to Headquarters Company, First Marine Supply Depot. There, I had the same duties, but at a different location on the island.

The natives on New Caledonia were a mixture of several different island people. The Aborigines resembled the natives in a Tarzan movie. Others were Javanese from Java. The Javanese chewed beetle nuts and their teeth and gums were black. The French were the ones who ran the lemonade stands and the shops. So far as I could tell, they were all snobs. They were not very friendly, but I think that this attitude is ingrained in the French. The Aborigines lived out in the jungle and the Javanese mostly lived in town and worked for the French, who treated them only slightly better than they did the Americans.

The natives on New Caledonia were a mixture of several different island people. The Aborigines resembled the natives in a Tarzan movie. Others were Javanese from Java. The Javanese chewed beetle nuts and their teeth and gums were black. The French were the ones who ran the lemonade stands and the shops. So far as I could tell, they were all snobs. They were not very friendly, but I think that this attitude is ingrained in the French. The Aborigines lived out in the jungle and the Javanese mostly lived in town and worked for the French, who treated them only slightly better than they did the Americans.

I didn't travel the island. For the most part, the Marines stuck together and just wandered around Noumea. A few Marines and Sailors "mingled" with the French, but only a few. A few Marines and Sailors spoke French and got along well with them. Almost everyone on the island spoke some English.

I didn't travel the island. For the most part, the Marines stuck together and just wandered around Noumea. A few Marines and Sailors "mingled" with the French, but only a few. A few Marines and Sailors spoke French and got along well with them. Almost everyone on the island spoke some English.

There must have been a million service men on the island, and if the fleet was in, that would be two million (with a b). It's hard to explain and hard for someone to understand who wasn't there. The Marine Corps kept us pretty busy, so we didn't think about liberty too much. There was a whorehouse called the "Pink House" that was quite famous throughout the South Pacific. At any one time, you could see a line of Marines and Sailors about a half-mile long waiting to get in (don't ask).

I don't remember there being many soldiers on the island. Mostly Marines were stationed there, and where you find Marines, you will also find sailors. When the fleet was in, the Sailors outnumbered the Marines. They always had more money to spend because they had been out to sea and didn't have any place to spend their money. There were some Soldiers, but I have no idea what outfits. I do remember that there was a Cavalry outfit and they had horses, but I don't know anything else about them. Marines didn't associate with Soldiers (integration hasn't gone that far).

I don't remember there being many soldiers on the island. Mostly Marines were stationed there, and where you find Marines, you will also find sailors. When the fleet was in, the Sailors outnumbered the Marines. They always had more money to spend because they had been out to sea and didn't have any place to spend their money. There were some Soldiers, but I have no idea what outfits. I do remember that there was a Cavalry outfit and they had horses, but I don't know anything else about them. Marines didn't associate with Soldiers (integration hasn't gone that far).

I stayed on Noumea from December 23, 1942 until about March 1944, living in an eight-man tent that we shared with the mosquitoes. During that time, USO shows came and went. I didn't see one, and Joe E. Brown is the only one that I remember that was there. I believe his son was a Marine who got killed on Guadalcanal. There wasn't much else to do on the island, so my strongest memories of this duty station was the boredom.

In about March of 1944, First Marine Supply Depot was transferred to Camp Catlett, Hawaii. Was I glad or sad to move from some French, mosquito-infested dump to the Paradise of Hawaii? I was glad! However, I don't believe that I did anything different after the move. On New Caledonia, the ratio of military to the islanders was about 100,000 to 1. On Hawaii, the ratio of military to the islanders was about 100,000 to 1. So you see, only the scenery changed. In Hawaii, I didn't have to sleep under a mosquito net. After over 60 years, I can't remember which I disliked the most on Noumea - the French or the mosquitoes. I would guess the mosquitoes, but only because there were more of them.

Camp Catlett, Hawaii was located about midway between Pearl City and Honolulu. I saw the devastation in Pearl Harbor of the Battleship Fleet. We had good liberty in Hawaii, but there must have been a million (with a b) soldiers, sailors, and Marines there at the time. Honolulu had photo shops, beer joints, tattoo parlors, whorehouses, and souvenir shops, but not much of anything else. Paradise it was not to the million (with a b) enlisted men on the island. It had pretty scenery, but little else. I was assigned to that duty station in Hawaii from March of 1944 to the summer of that year, when , I was transferred to Love Company, 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines, 2nd Marine Division. This was after they had returned from Tarawa.

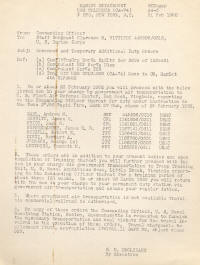

The division was fighting on Saipan when I left Hawaii by troop ship to join it. There were approximately 1,000 replacements for both the 2nd and 4th Divisions. Being new to combat, I was very apprehensive. It's always strange when you join up with an outfit that has seen fighting together. They trust each other, but not the stranger until he has been tested, and that doesn't come easy for them. It takes time. I was scared. Scared of the Japanese and also scared of the other Marines in the outfit. I really didn't know what to do, and most of all, I didn't know what not to do. So I moved very carefully. I listened very closely to the guys in the outfit and tried to do exactly what I was told. There were several of us that joined the platoon and a couple of us that joined the squad to replace those who had been killed or wounded. The squad leader took us in hand and told us what was expected of us and to obey our fire team leader. This, I can assure you, we did.

I had never had any combat training. I'd been with a guard company. So, as the new man, I got the bottom of the pecking order. I was assigned to be the Assistant Browning Automatic Rifleman (Assistant BARman). That meant that I carried ammunition for the BARman, as well as my own gear. During this time, a Marine Rifle Platoon had 42 Marines and one Navy Corpsman, and they were broken down as three squads of 13 men each. Generally there was a Sergeant as Squad Leader, and three Corporals as Fire Team Leader. A Fire Team usually had a Corporal Fire Team Leader, a rifleman, a BARman, and an Assistant BARman. They also had a platoon guide (generally a sergeant), a platoon sergeant, and a second lieutenant as platoon leader (4x3x3+1x3+1+1+1=42).

The platoon I joined was dug in and awaiting orders to go on patrol. We were in jungle terrain--there was nothing man-made around us. My Squad Leader was Corporal Shelby from Detroit, Michigan. That's about all I remember about him. My best buddy was a Marine from Oklahoma City, Oklahoma--a Marine I was going to remember the rest of my life. I've forgotten his name.

The day after I joined the platoon, we were out on patrol. We were mostly seeking lone Japanese who got separated from their units during the fight, and turned into snipers. While on patrol, we came across a small group of Japanese, perhaps as large as a squad. (At the time, I thought it was a division.) They started shooting at us, so we hit the deck and started shooting back. This went on for several minutes, although it seemed like hours. Then we got up and started moving up to where we thought they had been shooting from. We scouted around but found nothing--no dead, no wounded, nothing. However, they didn't hit any of us either, so I guess you could call it a draw. That was the first time someone was shooting at me. After the shooting stopped, I calmed down, but I never got over being scared when someone was shooting at me. We had no big organized resistance against us on Saipan. Instead, there were always small groups and snipers, so we had to always be aware of the fact that there was danger around us at all times. There were several wounded in my company who may have died of wounds later, but none were killed in battle. The number of casualties we suffered depended on the size of the group we ran into, as well as their firepower (i.e., mortars, machineguns, or rifles). Usually, they just had rifles.

The Japanese enemy on the island were a good, skilled, well-trained fighting force. Their banzi charges scared the hell out of us. I often thought that if Marines made a charge like that, we'd give them medals. When the Japanese did, we called them crazy and fanatics. We fought them sporadically, seeking out small groups of them and snipers who were hidden in the caves and jungle. I'm not sure, but I don't believe that there were any prisoners taken on Saipan. Plenty of Japanese soldiers and civilians jumped off of a cliff upon the defeat of their army, but I was not personally a witness to that.

We went out on patrol almost daily, but returned to our bivouac area each evening, rarely staying out overnight. Our mode of transportation was walking. We saw more jungle. There were few roads on the island, and those that existed were only along the coast. None of them were paved. There were trails in the jungle that were made by the Japanese who had been fortifying the island for years. There were no villages--no vehicles--no inhabitants, at least none that the Marines I was with saw. There was a village called Garapan, but I never saw it until much later. The only vehicles I saw belonged to the Marines. I saw no civilians. This was not a big country--only a small island.

There were three American divisions on the island--the 2nd Marine Division, 4th Marine Division, and the 29th Army Division. This amounted to well over 50,000 Americans. As a private, I had no idea what the American objective was on Saipan. I didn't even know the objective of our squad. I didn't even know what was going on anywhere except in a radius of about 50 feet around me. We did as we were told and the officers made the assignments. I'm sure the objective was accomplished, whatever it was. For me, the most difficult aspect of being on Saipan was being shot at.

A couple of weeks after I joined my company and Saipan was secured, we made a landing on Tinian Island. Tinian is the island that the Enola Gay later flew from to drop the first Atomic bomb on Japan. When it was dropped, it ended World War II. The island had a flat plain on which to build a large air base for the big bombers. At the time, it was the closet air base to Japan. It was only a few miles from Saipan, and only took a couple of hours to get there from Saipan via landing craft.

We had only a squad of Marines and their equipment on the craft, landing on Tinian around noon. I carried my M-1 rifle with full belt and a couple of bandoliers of ammunition for myself, as well as additional ammunition for the BARman, and a shelter half. Our 12th Marines, which was the artillery regiment of the 2nd Marine Division, had fired their guns at the island for weeks across the bay before we landed. I believe every capital ship the Navy had was bombarding the island. The Marine Air Group had also strafed the island, bombing any structure standing. It is doubtful if all this firepower killed any Japanese. Instead, it only made fox holes for them. It takes the infantry to win the battle.

Resistance, as I recall, was light according to those who had made the landings on Tarawa and Saipan. This was my first landing, so I had nothing to compare it to. The number of enemy was low because they had used their main force on Saipan. They were well-disciplined troops, but I'm sure their morale was very low because they had witnessed the devastation of Saipan.

I have very limited remembrance of the action while there. I remember the noise and being scared and shooting in the direction of the enemy. If you want to know whether I hit anyone that I shot at, I'll have to say I don't know. People were killed, but if I killed them or someone else in the platoon did, we'll never know. As for those in my squad, we had a few WIA's in the squad, but none killed. I have no idea who they were or just how they were wounded. We took no prisoners, and no Marines were taken prisoner.

I can't really describe my experiences in the first 24 hours of being on Tinian. The enemy was close. They shot -- we shot. We moved forward -- they moved backward. We dug in for the night, laid down our MLR, and then prayed the Japanese would get a good night's sleep. We walked, ran, or crawled to each new location, fighting all the way. We didn't see any village or civilians as we moved. We considered everyone in front of us as the enemy. Unlike Saipan, where all the large organized fighting units of enemy troops were gone by the time I joined the company, on Tinian there were well-organized and disciplined fighting units. The battle against them lasted only about 10 to 12 days. Of all the battles in the Pacific, this was probably the easiest island for the Marines to win. I can think of nothing that the Marines thought was difficult in meeting their objective on the island.

After about two weeks, we went back to Saipan into bivouac. We set up tents and started training for the next battle. We were in training for four months, and knew that it wouldn't be long before the next landing. We didn't know where it would be, but we knew that it would be a lot closer to Japan, and that it would be a hard one.

There would be no more battles for me to fight in World War II, however. In December of 1944, word was passed down to me that my overseas time was up. I had been overseas for 24 months, and at that time any Marine who had been overseas for that length of time was sent home. I was very glad to go, too. I don't remember the name of the ship that took me back to the States, but it was the slowest the Navy owned at the time. It arrived at Treasure Island Naval Base in San Francisco Bay on January 4, 1945.

From San Francisco we (there must have been about 1,000 of us) were routed to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, by troop train. In San Diego, we were given physicals and issued new uniforms. We were all given 30 days furlough and caught the train from San Diego east. This was not a troop train per se, but most all of the passengers were Marines in uniform. No one in the military at that time was allowed to wear civilian clothes. At St. Louis, we split up and most went north to Chicago. The rest went on east to Cincinnati and Pittsburg. Mom met me at Union Station in Cincinnati and took me to her apartment in Newport, Kentucky.

I'd been gone two and one-half years. Most all of the guys I'd known before I enlisted were now in uniform and away from home. I remember that I was treated great by everyone. I was in the Marine Corps green uniform, just back from two years in the South Pacific, with a PFC chevron and a 2nd Division patch on my sleeve. I wore one ribbon (Asiatic Pacific with star) on my chest. I felt proud, and I remember that everyone treated me great.

While I was in San Diego, I had been given orders to report to Post Troops, Parris Island, South Carolina. After my furlough was up, I took the train to Parris Island, South Carolina. This time I traveled alone. It was the same route I had taken a couple of years before, but the reception at Parris Island was a little different. I reported to Post Troops in February 1945. This was a kind of miscellaneous outfit that performed any kind of duty that had to be done. Mostly I worked at the water purification plant.

Parris Island is about forty miles north of Savannah, Georgia, and about 70 miles south of Charleston, South Carolina. Both were good liberty ports. Depending on the time we had and the transportation available, we would make trips to these two ports. At Beaufort, which is just outside the gate at Parris Island, there were always too many Marines (thousands) in every bar and restaurant. That kind of competition you wanted to do without if at all possible.

I was working at the water purification plant when the Atomic Bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. I can remember what a relief it was that it was dropped. I had been back in the States about nine months, and was about ready to be returned to the Pacific for the invasion of Japan. A group of us went to Savannah, Georgia, to celebrate VJ Day. It was a blast. The whole city was in a festive mood, and we celebrated for several days, I believe. Then, with the war over, I took my discharge (October 20, 1945) on points, and went home. I was in the US Marine Corps Reserve at the time.

It didn't take me long to realize that I had better get back in the Corps where I could get three meals a day and have a place to sleep. There were too many other people getting out of the service and looking for work who had a far better education than I. So, I reenlisted on December 28, 1945, and was sent to the Marine Detachment, Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island.

This was good duty, with about 40-50 Marines stationed there. We did guard and orderly duty for the senior officers at the college. I stayed there until about April or May of 1946, when I was transferred to Camp Pendleton, California, to join a replacement draft being sent to Tientsin, China.

I arrived in Tientsin, China, in June of 1946, where I joined Charlie Company, First Battalion, First Marines, First Marine Division. It was the same platoon that my brother Lloyd Allen had left only a month before. A few of the men who had known him helped me fit in with the platoon.

This was mostly guard duty, but more importantly, it was a way of letting our presence be known to the Chinese communists. With U.S. Marines there, they weren't about to attack the city. We patrolled the roads around our area and kept the road open between Tientsin and Peking. This one-lane gravel road was the main route between two of the largest cities in China. Sometimes we also rode the train between Tientsin and Chinwangtao, checking the bridges. We guarded warehouses that mostly contained the Marine supplies., wherever they may be located.

I only got to Peking once, and that was for three weeks. We fired the rifle range there, and stayed at the Italian Legation Building. There wasn't much difference between Tientsin and Peking. Both were beautiful old cities that smelled the same. The people were also the same.

We had plenty of liberty in China. I was able to see the Great Wall of China, which was a highlight of my stay there, as well as a few of their temples. Other than that, once you have seen a city in China, you have seen them all. I'm afraid I wasn't much of a tourist. At the time, I could have told you about most of the bars in town, however.

We moved around every once in a while, although I am not sure why. When I first got there, we were billeted in the "British Compound", and after a few months, at the "French Arsenal." Then later we were at the "Japanese Girls School." Our Company Commander was Captain Meeks. Our platoon leader was Lieutenant Smith. Smith was a long distance runner (he ran around the arsenal every morning). Our platoon sergeant was Gunny Sergeant Shipp.

The area in and around Tientsin was flat as a billiards table. The principal mode of transportation was by sulair (spelled phonetically), which was a two-wheeled buggy, seating two, pulled by a man on a bicycle. Later in Tsingtao, the mode of travel was by rickshaw, which was the same kind of vehicle, but pulled by a man generally running or walking. Tsingtao is in a hilly area, and the vehicle could not be pulled by bicycle.

The Division left Tientsin and moved to Tsingtao, China, in about May of 1947. At this point, I was given a 30-day leave. The only other time I got furlough was when I returned from the Pacific. In China, I had over 60 days leave on the books and was told that I had to take 30 days. The only thing I remember about this furlough was attending the wedding of Les Phillips and Bea Griffin with my Mom in Lebanon, Kentucky. Nothing else eventful happened. I returned to China around the middle of July. The trip both ways was by a MATS airplane. It was my first airplane ride.

I stayed in Tsingtao until the following summer, when I left China to return to the States. During my tour of duty in China, we ran into communist units several times while on patrol, but they backed off. There were no fire fights with them. I'm sure they were under strict orders not to fight us.

I liked China as a duty station. What was not to enjoy? We had a houseboy that took care of everything but our weapons. If I remember right, there were four of us sergeants living in a large room together. We ate in the Sergeant's mess and belonged to the Sergeant's Club. Our duties were light. We had liberty almost every night and every weekend. This was living high on the hog. I enjoyed it so much that I would have stayed longer if allowed to do so, but two years was the limit for us to stay there.

Upon my return from China, I was stationed at the Naval Ammunition Depot (Shumaker) in Camden, Arkansas. Even the train dispatcher had a hard time finding Shumaker. It is located just a few miles east of Camden, Arkansas, in Ouachita County. I arrived there in June and my enlistment was up in December. Generally, the duties there included guarding and patrolling a large ammunition depot, plus manning the main gate. I didn't actually patrol or stand the main gate watch. I was a Sergeant and was Sergeant of the Guard.

I was on a three-year hitch at the time. I remained at Shumaker until my enlistment was up, and then I took my discharge and went home to Mom's. At the time, I thought I wanted to leave Arkansas. On January 7, 1949, I reenlisted. The Corps always tried to station us where we requested if they could. I tried for small stations when I could. Small stations located away from large Marine Corps camps as a rule had better liberty, and it helped cut down on competition. No Marine Barracks is far away from good liberty. I was single and considered myself a "lady's man" (kind of like John Paine, the movie star), so why take chances. This was peacetime, remember. Small stations were good duty, but you seldom could stay there for any length of time. There was always someone else who wanted the small station, too. The Corps as a rule stationed you at least two years, but not more than three, at any one unit. As for me, I tried to stay out of the Fleet Marine Force (FMF) when possible--away from the crowd.

At the beginning of this enlistment, I was sent to Marine Barracks, U.S. Naval Disciplinary Barracks, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, as a guard. For years, this had been the Naval Prison and was still referred to as such by Marine and Navy personnel. There were two Marine Barracks at Portsmouth. Marine Barracks at the Navy Submarine Base stood the main gate watch and patrolled the base. We guarded the prisoners and the gate leading into our barracks. The base was not actually located in New Hampshire. Instead, it was located in Kittery, Maine.

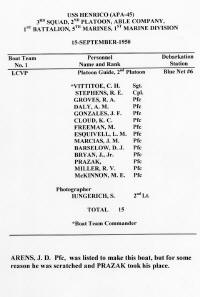

I stayed at the Prison until the spring of 1949 - about April - when I was transferred to the U.S. Naval Ammunition Depot in McAllister, Oklahoma. The Depot still exists today, but under the name McAlester Army Ammunition Plant. This was really good duty, but again you couldn't stay at a small station for very long. I was at McAllister until the following spring when I was transferred to the Fleet Marine Force (FMF). Then, about May/April, I was transferred to the 2nd Platoon, Able Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division, Camp Pendleton, California. As I remember, we only had 30-35 men in the platoon. Generally, a few of these were on leave, TAD, or in sick bay. This was better duty than I had expected. We were out charging over the hills daily, fighting aggressors, climbing mock-ups, and climbing down cargo nets almost daily. However, we had most every night off and every weekend, Camp Pendleton is located about half-way between two of the best liberty cities in the States.

Why did I rejoin? After you've been in the Corps for a few years, you never join an outfit anymore as a stranger. There is always someone you know well or someone who knows someone you've known well. It becomes a way of life. And I enjoyed being a Marine. With the exception of Sea Duty (which I didn't like), I never had what I would term "bad duty." Of course, I didn't like being shot at, but you had to take what was issued and move on. If I had it to do over, I'd ship over again.

I got to Pendleton in March and the Korean War broke out in June while I was involved in infantry duties. I knew nothing about Korea, and I didn't want to go to war, but if the Marines went, I wanted to go with them. I followed the war news by radio and newspaper, and, like MacArthur, I thought that it would be over in a hurry.

Marines with far better memories and writing skills have written all about the Korean War. They remember who, what, when, where, and why. I remember very little of what was going on during this time. From about the middle of June to the time we sailed for Korea was a time of confusion. We were receiving replacements daily. Also, some that had been TAD were returning to the company. One such was S/Sgt Charles Martin. I had been Platoon Guide since I'd joined 2nd Platoon, but when Martin returned from TAD, he being senior to me became Platoon Guide and I became squad leader of 3rd squad.

Before the war, we didn't have a 3rd squad. When the Brigade started its build-up, we had Marines come out of the woodworks. Some came from guard units all over the western United States, and even some reserve units were called up for active duty. Some hadn't been in a line company for several years, and some had the wrong MOS. These Marines may have had to take positions under Marines of lower rank than themselves. This didn't last long since all Marines are infantrymen first. By the time we arrived in Korea, they were in the position their rank called for and able to handle the position well.

I had no wife, and I had no car at the time I shipped out to Korea. My personal preparations before leaving were to pack my sea bag and ship my civilian clothes home to Mom. I called her and told her I was sending her my civilian clothes and that I was going overseas. At the time, we thought we were going to Japan for more training, but I think that Mom was a little worried.

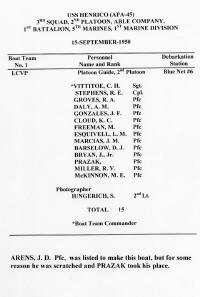

I'm not sure of the exact date we left for Korea. It was in the middle of July. We were aboard the USS Henrico. I have no idea how many troops it could hold, but it was a crowded troop transport filled with the men of the 1st Marine Provisional Brigade and their equipment. Only Navy and Marine personnel were onboard, and the cargo was our equipment. Our Commandant, General Clifton B. Cates, was at dock side to bid us God speed. This was the first time I had seen a Commandant or a four-star Marine General. I think he was talking to me personally when he said, "Clean up that mess in Korea soon or I'll find out why." He never had to go to Korea.

My sea bag never got to Korea, either. It was supposed to join me in Japan, I believe. But since we didn't go to Japan, I never saw it again. I've always enjoyed blaming the Navy for this mix-up. My sea bag had all of my uniforms in it, but nothing of value that couldn't be replaced easily. I've always traveled light.

The Henrico was an older ship that had been used in the Spanish American War around the turn of the century. Shortly after leaving the port, we had to go into Oakland for repairs. As a Sergeant, I had no idea what repairs were needed. The Marines aboard claimed it was because there was a movie showing Bert Lancaster that the Captain wanted to see, but this might be stretching it just a little. I believe we were in Oakland for about 24 hours or so. I don't remember if we caught up with the other ships in the convoy, but we all arrived in Pusan about the same time.

There wasn't much to do on the trip over. We saw a few movies on the fantail. We did calisthenics when we could find space topside--most anything rather than lay around all day. We had no duties, but Lieutenant Johnston and Gunny Lawson held several lectures on various subjects. I think it was more to have something to do than to impart something of use. No one knew much about Korea, and I believe most of the lectures given were guess work. They were about climate, terrain and the varmints we might run across. We knew almost nothing about the North Korean Army. Lieutenant Johnston had not been in World War II, but he was a very smart officer and could have given an interesting lecture on almost any subject. Gunny Lawson had been in several battles during World War II, and tried to explain what he could about an armed enemy-any armed enemy. I don't believe anyone can explain the horrors and fears of war. You have to live it to understand it.

I was soon to discover that the training I received in basic and advanced training in the Marine Corps would serve me well in Korea. We had been running over the hills and through the fields, up mock-ups and down cargo nets and attacking aggressors in a small village at Camp Pendleton all spring and summer. Only a few weeks before the war broke out, we had been on amphibious maneuvers off the coast of Southern California. (I don't remember the name of the ship.) We were onboard ship for approximately a week and climbed off into an AmTrac vehicle. These were tracked vehicles with large engines on each side. The troop compartment heated to a high degree. After climbing in, we had to rendezvous with the other vehicles in our wave for about an hour (seemed like years). However, the bad part was when we started into the beach. They closed hatch and the inside of the craft became like a dark oven. One of two guys got sick and the aroma just about did all of us in before we hit the beach. We were glad to hit the beach and start up towards California Highway 101. The claim at the time was that it was more dangerous crossing the highway than the enemy would have been on a defended beach. (This claim may not be true.)

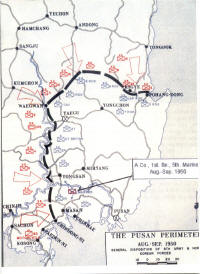

The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, the only trained infantry unit in the so-called Pusan Perimeter, landed in Pusan, Korea, about noon on August 1st, I believe. My first impression of the country was that it smelled just like China and it looked a lot like China. We got off the ship, where we were met by a Korean band that played the Marine Corps hymn off key. We then boarded a train that took us west. It was kind of like the passenger trains you see in the old western movies, and the seating was about the same. It was steam-powered, but I believe that it was narrower than our trains in the USA. It was preferable to walking, although not much faster. I have no idea how far we traveled before we disembarked and started walking. I also have no idea how far we hiked, but it wasn't too far. Then we spread out and dug in for the night.

My platoon leader was Lieutenant Johnston, a very ambitious Marine. He had every intentions of becoming the Commandant of the Marine Corps someday. I believe he would have made it if he had not been killed in Korea. He had all of the qualities necessary for such a high position. As I mentioned before, he had not been in World War II, but he knew everything about it that could be gained from books. He was an avid reader of the Corps' history. Physically, he was about 5'9" and weighed in at about 120 pounds soaking wet, but he was a big Marine. Gunny Lawson (a Staff NCO) had been a drill instructor and had also been in a couple of battles in World War II. These two men complemented each other. In reading this, you have to keep in mind that officers and staff non-commissioned officers did not fraternize with the lower ranks. They were our leaders, and the best thing I could say about them is that we trusted them to lead us.

That first day, they led us west of Pusan on the Masan Road. We saw plenty of Koreans along the way, and we assumed they were on our side. It was still daylight when we dug in for the night. Lt. Johnston and Gunny Lawson were able to place us where we had a good field of fire if it became necessary during the night to fire at the enemy. We were told that there was no enemy in our vicinity, but that we were to stay alert. This was our first night in enemy territory and everyone was on edge. We were tense and nervous, including some of us who had seen action before. We were at a 50 percent watch--that is, one slept while one stood guard. After nightfall, tree stumps turned into the enemy and bushes took on the look of men. It only took one man to fire a rifle in this atmosphere and several others followed. Lieutenant Johnston and Gunny Lawson told us to stand down and tried to calm everyone. All calmed down, but I think everyone was glad when morning arrived. So ended our first night. After that, I believe everyone felt calmer. The fear stayed, but it was under control after that first night. When going into combat, you are always apprehensive because you realize what is involved. We were scared, but we were able to handle it. As the weeks went by, we realized that you can only get used to the noise of combat. You can never get used to someone shooting at you. I saw my first dead enemy, as well as my first dead Korean War Marine, just a few days after landing. I didn't know the Marine. Seeing them dead did not affect me, although it was always bad to see a dead Marine - Semper Fi.

Our first objective upon arriving in Korea, I believe, was along the Masan road. Next was Chindong-ni, then Kosong, and then Sachon. Lieutenant Johnston was an officer and gentleman of the old school, but his vocabulary was taxed when he used the military map he carried. This was a map drawn by a Japanese engineer, and according to him, was all guesswork rather than exact measurements. The coordinates were so fouled up, Johnston was careful to call mortar fire well in advance of where he wanted it, and then bring it back to where it was needed.

The battle along the southern road to Sachon was continuous, so no particular battle stands out in my mind. When we were withdrawn from there, we trucked to the railroad. We rode the train for a while, then boarded trucks for a while, and finally hiked for a while. Then we arrived at the Maryang River (at least, I think that was the name of it). We had a bath and went swimming. It was very hot, and the high temperatures had a great effect on the troops of the Brigade. We withstood the heat in t-shirt and shorts, dungaree blouse and trousers, canvas leggings, socks, field shoes, and helmet with camouflage cover. It was hot and humid, and we were always thirsty. Several had heat prostration and had to be cared for until they were cooled down and able to continue effectively. I don't know how you can train for either the heat or the thirst. You just have to live with it and do the best you can. Odd as it may seem, it helps to know that those with you are suffering along with you and take pride in the fact that if they can do it, you can do it better. At least the swim in the river was welcome relief from the heat.

The next day, we engaged in the first battle of No-name Ridge, also known as Obong-ni Ridge, Red Slash Hill, and a lot of other names that are unprintable. The hill was located just east of the Naktong River close to Miryang. It had a slash in the ground (not man-made and about 25 to 30 feet in places) that looked like red clay and went down the hill. We didn't pay a lot of attention to it; we just saw it and someone called it a red slash and others picked up on the name. The hill was situated in the northwest area of the Pusan Perimeter. If I remember right, there were three high peaks on it. The slash divided two of them. Able Company had the hill on the left of the slash and Baker Company had the one on the right. The third was higher, but some further distance closer to the river and a little higher. It was no problem for 2nd Battalion to take it after we had the first two.

Obong-ni Ridge had originally been held by Army troops, but they lost it when they couldn't hold it. The Army units we came into contact with in the perimeter were useless as combat troops. They knew it and the Marines knew it. They had been Constabulary and Parade units in Japan, and had little or no combat training at all. They had officers who had no training with combat units, therefore, the army didn't know what it was doing. Without good leaders, no military unit is able to function against a well-trained enemy. Their morale was nil and the ones I observed were dispirited and useless as a fighting unit. If you want to scare a Marine unit of any size, just tell them, "Your flank is covered by the Army."

The objective at Red Slash Hill was to push the North Koreans back across the Naktong River and turn the hill back over to the Army to hold. We couldn't allow the North Koreans to hold it or even cross the Naktong River, because it would open the way for them to move into Pusan and push us out of Korea. The 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines tried the morning of the 17th to take the hill, but was repulsed. Then, the 1st Battalion tried that afternoon. This one battle (which lasted more than one day) cost us almost half of our platoon, including Gunny Lawson. Gunny Lawson was hit on the 18th. Prior to that, S/Sgt. Charles Martin had been wounded on the 15th on the road to Sachon. When he was hit, I became platoon guide.

We started up the hill (Red Slash Hill) in the late afternoon. The North Koreans were on top of the hill, trying to keep us from getting there. While this was going on, the Koreans tried to flank us with four unprotected T-34 tanks. The tanks were taken care of by the recoilless rifles and bazookas. Only a few Marines were able to make it to the top, so we weren't able to hold it because the rest of us couldn't make it. Darkness was falling fast. So, we dug in on the slope of the hill and prepared for the counter-attack that we were sure would be coming. We were armed with M-1 rifles. Our weapons worked well and we had plenty of ammunition and grenades to meet the enemy attack.

That night, the gooks hit us hard. At about 0200, they attacked us with whistles, bugles, and lots of automatic gunfire. They screamed and hollered, with machineguns firing on full automatic. They knew where we were tied in with Baker Company because they had watched us the evening before as we dug in. They ran right through us, managing to drive a wedge between Able and Baker Companies. They split second platoon in the process. The battle raged for a couple of hours. Their intentions were to drive between the two companies, but they were a little off. With the help of flares from our 60mm mortar section, we were able to see enough to keep them from completely overrunning us and keep control of the area. We shot some North Koreans who were only inches away from us. We felt it was easier to shoot them than fight them hand-to-hand, if at all possible.

We were never pushed off the hill once we started up. We were only pushed back to a lower position on the slope. We were also split where the North Koreans rushed through. My foxhole was on the right side of 2nd platoon, where Able Company was tied in with Baker Company. When the North Koreans attacked, I drifted on right into Captain Fenton's Baker Company's area. I had lost my helmet and ammunition belt along the way, although I still had a bandolier of ammunition around my neck. Otherwise, I was fine. A few of us then just joined up with Baker Company until things got straightened out and we were able to rejoin Able Company. Baker Company had been on a little higher ground than Able Company and were not pushed back. They held their position.

The loss of men and firepower affected us, but we had the use of air power, artillery and also of heavy mortars (81mm) from Weapons Company to help us. As it became daylight, we were able to fight back without shooting each other. Because it was still summer, sun up came early. As soon as we were able to see what was going on, we started pushing the North Koreans back. On the morning of August 18, we pushed the North Koreans over the top of the hill, down the other side, and across the river. It is difficult to say how long it took. During the heat of battle, time is not measured in hours.

When the sun came out, we could see that there were bodies all around--those of Marines, as well as gooks. Among the dead was 2nd Lt. Thomas H. Johnston, platoon leader of 2nd' Platoon, Able Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines. He was the platoon leader when I reported in to Able Company in California. He had trained us all during the spring and summer. We had just finished amphibious maneuvers off the coast of Southern California when the war in Korea started. He was a casualty of the battle for Obong-ni. Lt. Johnston was one of the finest and most ambitious officers I ever knew in the Corps. I don't want to imply that he was my friend--he wasn't. Sergeants were not friends with their platoon leaders in the Corps. He was the leader of 2nd platoon, and as such, he was respected and obeyed. He was killed the evening of August 17, 1950, on Obong-ni Ridge charging up the hill to push the North Koreans off. I admired and respected him for what he was--my platoon leader. He was awarded the Silver Star (posthumously).

When it was possible to do so without too much danger, we (with help from some South Korean civilians) removed the body of Lieutenant Johnston, as well as those of our other dead, from the battle scene. Our Corpsmen also tended to the wounded, moving them to an aid station in the rear regardless. By the time the fighting was over, we had lost about half our platoon in the two-day battle, but we ultimately gained our objective. We stood, kneeled, and from the prone position fired at the gooks trying to cross the Naktong River. It was a shoot-out. We had excellent artillery, tank, and air support, too. Collectively, Marine power sent the North Koreans into retreat. While we fired at them, they tried to escape by wading across the Naktong. The enemy troops we were fighting were mostly young, good fighters, but they were ill-equipped. Where Marines always spread out, the North Koreans wanted to cling together. They had more automatic weapons than we did, and tried to spray an area. Marines had a different tactic, shooting at specific targets if possible.

Good leadership is the most important thing while fighting a war. Our loss of Lieutenant Johnston the afternoon before, and Gunny Lawson that night, obviously had a bad effect on the platoon. Although he wasn't able to do so until the 18th, our company commander, Capt. John Stevens, knowing we were in trouble, sent Lt. Frank Muetzel to us to replace Lt. Johnston. He also sent Gunny Sergeant Jessie Johnson to replace Gunny Lawson from the Weapons Platoon. Those of us who had been training in Camp Pendleton with the company before the war started knew both of them well, so there was no loss of trust in our leadership.

The Marines took Obong-ni on the 18th of August, and turned it back over to the Army. They were unable to hold it so the Marines had to go back and take it again. I'm not sure of the time element here, but I think we had to go back about the first of September. The Marines were not happy to have to go back to fight for the hill a second time. We had little respect for the army or its leadership.

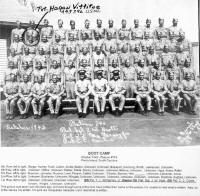

When we were pulled off of the battle line, we were sent back to Pusan about 3 September. We stayed at the "Bean Patch" near Pusan (I don't know why it was called that; I didn't see any beans), took another bath, and had our picture taken. We all thought that we were pretty tough Marines about that time. The pictures were taken by an Official Marine Corps Photographer. We also laid around in a warehouse waiting to receive new Marines to replace our dead and wounded. Those of us who had been around from the beginning were more mature and better fighters by now. Our officers could call in closer air cover and mortar fire. Both mortars and aircrafts had become more effected and better at their job by now as well. Obviously, if you survive a tough battle, you're more hardened and better prepared for the fighting ahead. We dazzled the new guys with our exploits (pilots aren't the only ones that can do that, you know). We told sea stories and bragged a little. I got my picture taken on September 6, 1950--my 25th birthday. We wrote letters and received mail. Also, we got a third Company in the Battalion.

After a few days wait, we boarded the USS Henrico about 7 September 1950. I remember that there was a rumor that Margaret Higgins was aboard, but if she was, I didn't see her.

My time in Korea was limited, as you will discover upon reading my memoir further. I want to stop here long enough to note that I have know a few of whom I believe were outstanding Marines, and they certainly don't need an endorsement from me. I served with five of them while in Korea:

We boarded the USS Henrico at Pusan on the morning of September 8th and arrived off the coast at Inchon the afternoon of the 14th (this is all guess work). We stayed onboard the ship and watched the fireworks as the ships in the outer harbor shelled, and the planes strafed, the beach area. On the trip to Inchon, we had been briefed that we would need to climb ladders to get out of our boat and over the sea wall. There were two ladders in each LCVP. But since no one had ever experienced this before, we were breaking new ground in amphibious warfare. We knew where our debarkation station was located and the location of the cargo net we were to use to get to our landing craft.

Inchon harbor was filled with all kinds of ships--every kind the Navy owns. I'm not sure it wasn't all the ships the Navy owned. I have no idea how many there were, and couldn't even guess. All I know is that there were a whole bunch. There was also Marine and Navy aircraft. There could have been Air Force as well, but I wouldn't know. I didn't pay attention to the aircraft other than watching them strafe and bomb the area. I don't remember now, but I'm sure it was noisy. I don't think they killed any North Koreans, but they did make them duck into their foxholes and trenches and keep their heads down.

On the evening of September 15, 1950, we landed at Inchon. We laid off quite a way from the beach on the Henrico, then climbed down a cargo net into an LCVP, boarding our landing craft with plenty of time to rendezvous with the boats in our wave. Our platoon was in the second wave. I'm not sure, but I believe we circled around in our rendezvous area for about an hour before heading into the seaway. The timing was important because of the mud flats. We had to land when the tide was at its highest so our landing crafts wouldn't scrape the mud bottom of the bay and stall us before we reached the seawall.

As we landed on Red Beach, it was getting dark fast. We were met with small arms fire, rifle, machinegun and mortar fire from the enemy. My platoon leader, Lieutenant Muetzel, moved fast toward our objective with the first and second squads just as soon as he landed. Any time you're out of touch with your platoon leader, you have a problem. By the time we (third squad) landed, he had already moved inland and it was up to us to find and join up with him. I climbed the ladder and went over the seawall, and then moved forward shooting at anything in front of me that I thought was a Korean. I tried to join up with Muetzel, but I didn't get very far. I was shot by a sniper after going only about 100-200 yards inland. Cpl. Ray Stephens took over the squad when I was hit and joined up with Lieutenant Muetzel a little later.

I got what was referred to as a "million dollar wound." That is, it was not bad enough to do permanent damage, but it was bad enough to get me the hell out of Dodge and sent home. The bullet went through the middle finger of my left hand, breaking the bone. It then went through my rifle stock and into the palm of my hand, breaking the same bone again in my hand. In the process, it sent splinters from the rifle stock into my palm, making it look worse than it really was. At the time I was hit, I knew I had been hit, but I didn't know the extent of the wound. I felt no immediate pain. I called the Corpsman, and he treated me as best he could. When he started working on me, that's when I began to feel pain. The Corpsman took out the splinters he could see, gave me a shot of morphine, and sent me back to an LST sitting on the mud flats in the seawall area that was the Battalion Aid Station. I walked there myself. By this time, it was fully dark. I stayed at the Aid Station until the tide came in the next day and we were able to go out to a hospital ship in the outer harbor. I was operated on there, and then transferred to a troop ship that was returning to Japan. I left the Korean War behind me, remembering it as an experience in which I was scared, hot, thirsty, tired and satisfied--not necessarily in that order all the time.

I went to the Naval Hospital in Yokohama, Japan, for a couple of weeks, and then was flown back to the States. (I don't remember if Hawaii was a state at the time or not.) Meanwhile, Mom got a telegram telling her that I had been wounded. She worried about how badly, but I was able to write to her and assure her that it was not serious and I would be home soon.

At the Naval Hospital in Hawaii, Lt. Gn. Lamuel Shepherd, Jr., Commanding General, FMF, PAC pinned the Purple Heart on my pajamas. Then we were flown on to California and I was admitted to the Naval Hospital at Mare Island, Vallejo, California, in early December 1950. I'm not sure of the exact date, but a little before Christmas I was transferred to the Naval Hospital, Great Lakes Naval Base just north of Chicago, Illinois. This was a little closer to home. I was there until about March 1951 (they were in no rush to release you from the hospital in those days), when I was released ready to return to full duty.

From the time I was operated on until about a week before I was discharged from the hospital, I had a cast on my arm and wires through my middle finger. The hospitals were full of Korean War wounded--all young, healthy men who, if not wounded too badly, wanted to go on liberty or to the slop-shoot. After getting back to the States, I had liberty almost every night--sometimes in a crowd and sometimes alone.

Did I have regrets at having to leave the other members of my squad behind? At the time, I could have given a more definitive answer to that question. Now, I just don't know. I've heard about men who were in the Vietnam War, telling how they volunteered for a second and third tour in Vietnam, and I've wondered -- why? What was their MOS? Were they in typewriter repair of some such rear echelon outfit? Did they ever hear a shot fired the first time they were there? Did they really expect to be stationed in the same outfit they had left and meet the same men they had left behind? In a combat unit, if you are gone only a few weeks, the men you left behind are now wounded or killed and have been replaced by others. When you return to your unit, you will be a stranger. Marines go where they are ordered -- they never volunteer for anything.

After I was sent back to the States, I also did not attempt to look up any family members of members of my company who had been killed in Korea while I was there. What could you say? There would have been nothing to gain, and sob stories are no help.

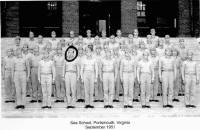

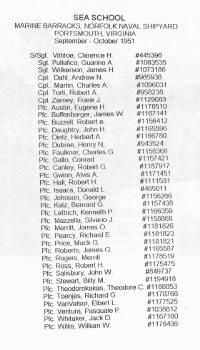

After my release from the hospital, I was transferred to the Naval Ammunitions Depot in Camden, Arkansas, again. The warrant for my promotion caught up with me just as I got back to the States while I was in the hospital in Mare Island, Vallejo, California. I was now a Staff Sergeant. At Camden, I stood Sergeant-of-the-Guard watch. This was good duty, but you could never stay at a small station for very long. The Navy closed the depot at Camden about August or September of 1951, turning it over to a civilian company. I was transferred to Sea School, Portsmouth, Virginia, studying there during September and October of 1951. The course was four to six weeks duration.

The instructors at Sea School were permanent Navy personnel stationed at the school. They mostly taught us the meaning of bells, pipes and whistles, and who received which honors and what those honors were to be. Although Marines use Navy terms in their speech, this was kind of a refresher course on terms such as deck, overhead, ladder, bulkhead, stern or aft, and forecastle. Little things like that mean so much to the Navy. (I am convinced that the real reason for Sea School is simply to irritate Marines.) Most of our studies were done in a classroom setting.

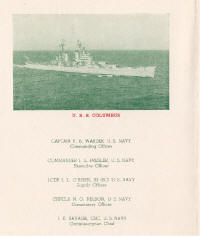

After graduating from Sea School, I was transferred to Marine Detachment, USS Columbus (CA-74). All the time I was with the ship, we were going up and down the eastern seaboard or in Boston Harbor. I liked staying in harbor best. I didn't like sea duty. Guard and ceremonial duty was not what you would call fun. Actually, I usually enjoyed guard and ceremonial duty out in the parade ground, but not in the confines of a ship. Example: "When the Commanding Officer of a ship leaves or returns to the vessel under his command he shall be attended at the side by the officer who, in his absence, succeeds to the command; and if of or above the grade of lieutenant commander the guard of the day shall be paraded in his honor if he leaves or returns officially. The full guard and band is paraded for flag officers officially coming aboard or leaving a naval ship or station. The guard of the day only is paraded for a captain, commander, or lieutenant commander (unit commander, chief of staff, or commanding officer) officially coming aboard or leaving a naval ship or station." Just little things like this.... I would not have minded guard and ceremonial duty, so long as it was not aboard ship.

On the Columbus, I was the Gunnery Sergeant with almost nothing to do. I shined brass buttons and shoes. The detachment also manned two "3 inch 50" gun mounts. I believe that means the diameter is three inches and they are 90 inches long, but I'm not sure. The guns were fired and aimed by radar control. I just sat there and pulled the trigger. Planes were too fast for human control. Besides the boredom of having little to do onboard, how could you impress the girls if you were at sea all the time? ,Besides, (1) I hated the sea. (2) I was never too fond of sailors. (3) The Navy serves beans for breakfast. Yack!

Several of us had been on troop transport, but only the 1st Sergeant, M/Sgt Fluhardy, had previous sea duty. He had been on a battleship during the 1920s. I went to our Detachment CO, Captain Wickham, and explained that I wanted to be transferred off the ship. I'm not sure if Captain Wickham felt sorry for me, or just wanted to get rid of me, but I really appreciated him approving my transfer. He transferred me to 8th Marines, 2nd Marine Division in Camp Lejeune, NC, in April 1952.

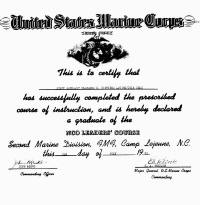

I then attended NCO Infantry Leadership School. This was the summer of 1952 during the months of June and July. I believe the class was six weeks long. I was qualified to attend because of my S/Sgt rank and my MOS 0316. I had been a Private in World War II, a Corporal in North China, and a Sergeant in Korea, but you could always learn something new and different in the Corps. It was always good to learn how to do your job better and to keep up with new ideas. Infantry Leadership School mostly taught NCOs to call in supporting units--air support, artillery support, and mortar support (both 81s and 60mm) and how to use them more efficiently and effectively. Some of the night classes on map reading and compass work I could have done without. Those hikes were over some of the worst terrain to be found on the base.

In the summer of 1953, I reenlisted with the understanding that the Corps would send me to Supply School, Camp Lejeune, NC. I wanted to try to get into some Marine Corps school where I could learn something that would be useful in civilian life. I was getting at the age that I started looking forward to the time I would retire from the Corps. I needed some training besides infantry training. This request was granted.

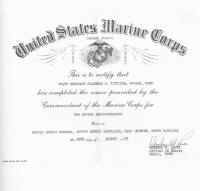

In Supply School, I learned basic typing, bookkeeping, and the use of office machines. After about four months, I graduated from Supply School and my MOS was changed from 0316 to 3000. I was then transferred to Marine Barracks, Naval Ordnance Test Station, China Lake, California, where I became supply sergeant for the detachment.

I was at China Lake until the spring of 1955, when I went to sickbay for a check-up due to a cough. They gave me an x-ray and thought I may have pneumonia. They flew me down to the Naval Hospital, San Diego, for tests. There, they discovered that I had tuberculosis. The Marine Corps placed me on a Temporary Disability Retirement status. This was to last for five years and then I would be reevaluated and returned to active duty or retired. After five years there was little chance that I would be returned to active duty and everyone knew it. But that was standard procedure.

When I was diagnosed with the disease, I had mixed feelings. Everyone of my generation had heard about "TB Sanitariums" and what horrible places they were. Almost every county in the country had a sanitarium. After talking to the Doctors there at San Diego and getting a better understanding of the disease, it became less of a concern. I was given medication for the tuberculosis, but the main treatment for it at that time was bed rest.

In late September or early October 1955, I was transferred from the Naval Hospital in San Diego to the Fleet Reserve. I was sent to the Veterans Administration Hospital, Dayton, Ohio. The treatment, as it was explained to me at the time, was to stay in the hospital and do as the doctors asked, or bounce in and out of the hospital for the rest of my life. I stayed in the Veterans Hospital until I was released in August 1957 (two years in pajamas).

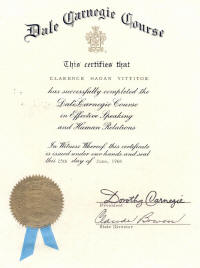

While at the VA Hospital, I studied and with the help of one of the doctors was able to get a GED from Chaminade High School, Dayton, Ohio. Upon release from the hospital, I moved to Los Angeles, California. giving my brother Jimmy's address in Santa Anna as my home address, and with the help of the GI Bill, I enrolled in Los Angeles City College and took business courses. One of the nurses at the hospital had recommended that college and I liked what she told me. I had an apartment at 803 N. Vermont Street just across the street from the college.

I found some of my fellow students to be less mature than I was, but many were not. Just after World War II, veterans by the thousands had returned to college campuses. Most of the instructors could still remember this. As for the students, they were for the most part about ten to twelve years younger than I was at the time.

I graduated from Los Angeles City College with an Associate in Arts degree in May 1959. I stayed in California until about November 1959, when I decided to move back to Mom's in Newport, Kentucky. The people in California, and in Los Angeles in particular, were a transient people. Even those who had lived there for years moved every year or so. I wanted stability in my life; hence, I decided to return to Kentucky.

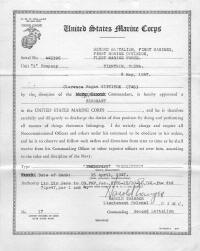

On 30 June 1960, I was discharged from the Marine Corps. It wasn't my decision to retire from the Corps. The Marine Corps retired me. Naval service at that time would not keep personnel with TB because of the close quarters aboard ships. There is no cure for TB. It is only arrested.

Soon after my return to Kentucky, I took Mom to the funeral of Uncle Henry Griffin, in Campbellsville, Kentucky. He was not actually my uncle, but we called him that. His wife, Kizzie Campbell Griffin, was Mom's first cousin. I was in the funeral home when Henry Griffin's daughter introduced me to her friend, Miss Wanda Eloise Settles. I had prayed for a long time that I would be able to meet a lady that would become my wife. Wanda was beautiful, about my age, single, and a Christian. Who could ask for anything more?

I didn't really have any trouble adjusting to civilian life after leaving the Marine Corps. I was in the hospital for a couple of years after leaving active duty and then in school for a couple of years, so there wasn't much of an adjustment to be made. I've always adjusted to my surroundings pretty well.