"At times this interview has been difficult for me. I have for all these years repressed the images in my mind of most of the horrific injuries that we in surgery worked on."

- Tony Ybarra

Tony Ybarra was a Navy corpsman during the Korean War, assigned first to the USS Haven hospital ship, and then the USS Consolation hospital ship. The following memoir is the final result of a series of questions/answers that were exchanged between Lynnita Brown of the KWE and Tony Ybarra in the year 2002.

My full name is Tony Ybarra. I was born on December 5, 1929, in Monterey, California. My parents were Cirilo and Herminia Delgadillo Ybarra, who emigrated from Mexico in 1925. My father's first job in the United States was as groundskeeper at the Pebble Beach golf course in Monterey. My mother worked in the various fish canneries in Monterey.

When we moved to San Jose toward the end of World War II, my father worked as a laborer in the housing construction industry. My mother worked in the fruit canneries. There were four children in our family. I had one sister who was older than me, and a brother and sister who were younger. We attended grade school in Monterey and high school in San Jose. During the school year I worked for the Western Union delivering telegrams. During the summer months I worked in the orchards picking fruit. In my junior year I finally got a job in a fruit cannery that paid much better. In the cannery I held several jobs, with the longest in the empty can department. I drove a lift truck, unloading pallets of empty cans and loading pallets of full cans onto trucks.

I was a Cub Scout in Monterey, and a Boy Scout in San Jose, but I was not too active because of my jobs. I attended all the meetings, but did not go on the camping trips, with one exception. I got to go to Yosemite for a week. I wanted to transfer from the Boy Scouts to the Sea Scout branch, but the only active unit was located in San Francisco. It was too far to travel, so I decided to join the San Jose Naval Reserve Unit at the age of 17.

World War II was going on while I was growing up. No one in my family was in the war, but we certainly followed the news about World War II. We were a coastal town, and we had heard rumors about miniature Japanese submarines that had been spotted along the California coast. We were scared to death about the possibility of being attacked since we were not that far from Pearl Harbor. We saved aluminum, string, and fat for the war effort. We bought war stamps. We donated to the USO. We also had air raid drills on a regular basis, as well as blackouts. We had room darkening drapes on all the windows.

I graduated from San Jose High in June of 1948. After graduating from high school, I continued working in the California Canners and Growers cannery. I also enrolled at Menlo Junior College in Menlo Park, which is a about halfway between San Jose and San Francisco. I completed two years of Junior college with an AA degree in 1950. I worked in the cannery that summer and decided to enlist in the regular Navy.

The Korean War broke out in June of 1950. I followed the news about the war because I was in the Naval Reserve. The possibility of our unit being activated was on all of our minds. We had heard that our reserve unit was about to be activated, but we had no idea how soon. It could be right in the middle of the school semester. I read articles about the war in the newspaper to keep abreast of what was happening in Korea.

I would have liked to join the Air Force, but I was told that basic training was in Texas. It got really HOT in Texas. Navy boot camp was in San Diego, California. I preferred California to Texas. Besides, I had a girl friend (Billie Genevive Mercurio) who was living in Los Angeles. I had met her in June of 1949 in Long Beach, California. Every year, our reserve unit had a one-week session aboard a destroyer. We sailed from San Francisco to southern California, and had gunnery practice at one of the small islands. I was a gunner's mate apprentice—one of five crew members on the five-inch cannon. One day we got liberty in Long Beach. I met my future wife at the Pike, which was an Oceanside boardwalk. I spent the day with her and then accompanied her home on the bus. I got her address, too. The ship sailed on to Catalina Island, a resort, the following day. When we returned to San Francisco at the end of our weekly training cruise, Billie and I began writing letters to each other on a regular basis.

I would have liked to join the Air Force, but I was told that basic training was in Texas. It got really HOT in Texas. Navy boot camp was in San Diego, California. I preferred California to Texas. Besides, I had a girl friend (Billie Genevive Mercurio) who was living in Los Angeles. I had met her in June of 1949 in Long Beach, California. Every year, our reserve unit had a one-week session aboard a destroyer. We sailed from San Francisco to southern California, and had gunnery practice at one of the small islands. I was a gunner's mate apprentice—one of five crew members on the five-inch cannon. One day we got liberty in Long Beach. I met my future wife at the Pike, which was an Oceanside boardwalk. I spent the day with her and then accompanied her home on the bus. I got her address, too. The ship sailed on to Catalina Island, a resort, the following day. When we returned to San Francisco at the end of our weekly training cruise, Billie and I began writing letters to each other on a regular basis.

My decision to join the Navy did not prevent our seeing each other. Both she and my parents respected my decision to enlist in the regular Navy, which I did on October 28, 1950. I had no friends who joined at the same time I did, but there were others from the Santa Clara County area who joined at the same time I did. We were sent to San Diego by train. I already knew what to expect in boot camp. While in the Naval Reserve I had signed up for a two-week training session at the same base.

We arrived in San Diego in the evening. The naval base in San Diego was a very flat area near the ocean. We got to see a lot of ships. The weather during October and November was very pleasant. There were no insects or other pests. We were transported to the base by a Navy bus, and then were temporarily housed in an unused barracks. The following morning we were issued our Navy clothing. We boxed our civilian clothes for shipment to our families, and then we were marched to breakfast. After breakfast we were introduced to our company commander, First Class Petty Officer E.C. Molyneux (not a World War II veteran). He asked if anyone had previous military experience, and several of us had. He assigned a recruit with ROTC experience as Junior company commander. Three others and I were made squad leaders.

Boot camp was eight weeks long. We started by learning to march. We marched everywhere. The classroom training was mainly naval history, etiquette, identifying types of ships, as well as flags. We were also shown documentaries on naval history up to World War II, as well as educational films on naval etiquette and venereal disease prevention. The World War II documentaries stuck in my mind. I have always been interested in historical events, as well as reading novels based on actual historical events. Our non-classroom training included parade marching, fire fighting, damage control, semaphore signaling, target practice with the M-1 rifle, rope knots, and ship navigation. I'm sure there were others that I don't now recall. The only proficiency test that we had before training was in swimming. We had to individually tread water for thirty minutes, and swim the length of the pool.

We were never awakened in the middle of the night. Our DI was a mild-mannered individual who never used corporal punishment. I appreciated our DI beginning with the first week of boot camp, just for the fact that he was able to take eighty raw recruits (all white because there was no big push for integration at that time) and train them as a military unit. I was never personally disciplined, but I did see others who were. Once, a few recruits decided to get in the chow line on their own. They were caught. Their punishment was to clean an empty barracks from top to bottom that same evening. I remember only one other incident in which a recruit was disciplined. He did not shower on a regular basis and wore dirty underwear. The DI ordered three in his squad to take him into the showers, bathe him, clothes and all. I don't remember having any troublemakers in our company. I remember only one recruit who didn't make it out of boot camp. His name was Herbert Carlos. He became ill, was hospitalized, and never returned to our company.

We were well fed in boot camp. It wasn't restaurant prepared meals, but I enjoyed every one of them. There were other good things about life in boot camp, too. Church services were offered, so I attended Catholic mass every Sunday. No DI ever breathed down our neck at that time. Billie came down to see me during boot camp, too. I had fun the whole eight weeks. I was never sorry that I joined the Navy. The hardest thing for me at boot camp was having to stand at parade rest for up to two hours. The rest was a piece of cake.

When basic training was completed, we had a graduation ceremony, along with a military band. We marched around a huge field and passed in review in front of military dignitaries, families and friends. I, for one, was very proud that day. My family attended. I left boot camp very satisfied with my training. I don't remember going on leave after boot camp. I was transported, along with three others from my company, to the San Diego Naval Hospital for hospital corpsman training.

I had not planned to request hospital corpsman training. I actually requested aerial photography training. I had had an interest in photography since junior high, belonging to several photography clubs while I was in school. I enjoyed taking photographs, and I had my own darkroom at home. But the Navy interviewer informed me that that particular school was no longer available. He said that my best bet would be hospital corps school for the following two main reasons: There was a need for hospital corpsmen due to the Korean War, and he noticed by my records that I had taken courses in high school and junior college that were considered pre-med. I had taken anatomy and physiology, chemistry, biology, and physics. I agreed to follow his recommendation with some hesitation. The hospital corps school was located at the San Diego Naval Hospital. I was not exactly elated with the assignment, but under the circumstances, I felt the interviewer knew best.

The duration of the school was nine weeks. In the classroom we studied anatomy and physiology, materia medica (drugs used in medicine), basic patient care (for illnesses and wounds), first aid methods, sterile technique, and hospital administration. In the labs we practiced sterile technique, IV transfusions, injections, drawing blood, taking blood pressures, administering medication, making hospital beds, and patient care. We also practiced applying plaster casts. I don't remember the names of any of the instructors. They all seemed to be very qualified in their subject area. I felt the training was comparatively easy for me. I knew of no one who did not complete the training.

I graduated from corps school on March 8, 1951. Since I was one of those who scored in the upper fourth in the class, I had the choice of selecting any naval hospital in the U.S. for my internship. I chose the Naval hospital in Oakland, California, since it was only 35 miles from my home. I fully expected to be assigned to a ward where incoming Korean wounded were cared for and treated.

To my complete surprise and dismay, I was assigned to the newborn baby nursery. I requested an assignment to a ward, but it was denied. My job was to bathe, comb, administer vitamin K shots, dress, feed, and care for the new arrivals. When the need arose I was also to assist in the delivery room. I learned to thoroughly enjoy taking care of all those babies. We had up to thirty at one time.

Billie would come to visit me every opportunity she had, and when I got liberty from my duties, I went home to San Jose. On some occasions I could get a free flight to the Naval air station in Mountain View (Moffet Field), where I hitched a ride to Los Angeles to visit Billie. On one of those trips I proposed to her and presented her with an engagement ring.

I had independent duty at least once a week for four hours after my regular full day in the nursery. I was assigned to care for a terminally ill adult. I took his or her vital signs, checked for bed sores, and performed general nursing care. I did not feel that I was going to be prepared to care for the sick and wounded from Korea if I continued in the nursery. I never did have combat corps school or field medical training.

I really had no plans to request for duty in Korea. I got to the point where I was perfectly happy working in the nursery. But my friend who worked in the premature nursery informed me one day that there was a posting in the office that I would be interested in. He knew I had a girlfriend in Los Angeles. He told me that corpsmen were needed aboard a navy ship in the Long Beach area. I jumped at the chance to sign up, because the ship would be permanently stationed at Long Beach. I would get to be with my girlfriend on a regular basis—so I thought. There was no such ship. What my friend and I signed up for was duty in Korea. I received my orders for duty in Korea around the end of July 1951.

Billie knew that I had inadvertently signed up for Korean duty. I phoned her to tell her that I was being shipped out to Korea in two weeks. She caught the Greyhound bus to San Jose, and stayed with my parents. That's when we decided to get married. We drove up to Oakland Naval Hospital and got tested. After that, we got the marriage license and then got married by a justice of the peace in Oakland on August 9, 1951. We did not tell our families.

My wife went home to Los Angeles and I reported for duty on the aircraft carrier Windham Bay on the 19th of August. I saw my wife when the ship went to Long Beach to pick up aircraft to be transported to Japan. No one was to get liberty, but I spoke to the Chaplain and he got me an overnight liberty. I did not see my wife until a year later, when the USS Consolation rotated back to the U.S. We stayed with her relatives. We had a very small religious wedding at the Mother of Sorrows Catholic church, but we did not set up housekeeping until I was discharged from the Navy in August of 1954. She lived with her girlfriends until she got a job in the mail department of the California Lutheran Hospital in downtown Los Angeles. She rented an apartment as soon as she had the necessary rent money.

Billie has added to my memoir with the following recollections of her own about that time in our lives:

"I had just graduated from high school, expecting to get married. I was making plans when Tony phoned me to tell me he had his orders to ship out to Korea. I could not believe it at first. Then I knew he was serious.

We had ten days. I was living in Los Angeles, but went to San Jose from Los Angeles to stay with his parents. We decided we would get married and not tell anyone until he returned. We drove to Oakland, got the required blood test at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital, and got the marriage license. We went into a courtroom where court was in session. It was going on for a long time. The judge looked at us and said, "If you people want to be married today, come on back to my chambers. He performed the ceremony with his secretary as witness. Actually, it was a very beautiful ceremony--the one I really held in my heart. We did have a church wedding one year later. We never did tell the folks about the first one.

I was able to get a job right away. I was so lucky to have found a job. It was at the California Hospital at 1414 S. Hope Street in Los Angeles. The staff of doctors and employees took me in like family. They were my support system. They counted the days with me. We turned a page in the calendar each month. We had the pages numbered how many days until his return. It was a very long time. I thought it would never pass. I wrote to him every day; sometimes two or three times a day. Every day when I got home to my little apartment I would check the mail box.

When he came home after being discharged from the Navy, we read some of the letters we had written to each other. We decided to burn them in the back yard incinerator. It was a HOT fire. Now our sons wish we had saved those letters. That's how we got through it--letters and knowing we would be back together."

- Billie

After that one night with Billie, I went back onboard the Windham Bay and it headed for the Far East Command and the Korean War. On our way to Japan, we stopped in Hawaii. My friend was transferred to duty in Hawaii. His dad was a politician with influence, so he got his son assigned to duty in Hawaii. Needless to say, he was no longer my friend.

The Windham Bay was a small aircraft carrier that had been converted to an aircraft/troop transport vessel during the Second World War. From what it was converted I have no idea. My guess is that it had a crew of 860 men. As far as I knew, it was based at the Alameda Naval Air Base, and from there it ferried aircraft to Japan from San Diego.

I was assigned a bunk in the enlisted men's quarters. It was the bottom one closest to the deck. There were four bunks in each tier, and about two hundred men in each quarter. The carrier had everything a small city would have: a library, movie theater, store, gift shop, ice cream parlor, barbershop, sickbay, and, of course, a huge mess hall. I explored the ship, going everywhere I was allowed. I checked out the flight deck, hangar deck, engine room, and every space fore and aft, including the anchor compartment.

The aircraft that were picked up in San Diego were single engine propeller driven, with wings that could be folded up during the trip. They were stored both in the hangar deck as well as on the flight deck. I don't know how many there were, but there seemed to be at least one hundred.

It was the first time that I had been on a large ship. I already had my sea legs, however, and never experienced seasickness. Actually, often during the year, our reserve unit had spent weekends on a destroyer. We would sail under the Golden Gate Bridge, sometimes under pretty rough weather with very choppy sea. We did not hit any rough weather on the way to Japan. It was smooth sailing. It took about fourteen days to get to Yokosuka, Japan. I watched a movie every night on the hangar deck, ate ice cream, checked out several books from the library, ate ice cream, practiced on the punching bag, read every day, and ate ice cream while I read.

The books were mostly about historical events and novels based on history. When we crossed the International Date Line, there were no ceremonies, but each one of us who had not been across before were given a certificate proclaiming that we were now officially Shell Backs. Four days out of Hawaii, I was reading one of my books in the hangar deck, propped up against the bulkhead, when a Chief Petty Officer spotted me. He asked me what my duties were. I told him that I was a passenger, and had not been assigned any duties. He said that he had something for me to do. As it turned out, my duty was to check out every aircraft in the hangar, twice a day, to make sure each and every one was properly secured. After checking every airplane, which took no more than an hour, I would sit in a cockpit and enjoy reading. I did that every day until we arrived at Yokosuka. I did a lot of reading. Nothing eventful happened on the trip.

I had never been to an Asian country before I got to Japan. The first Japanese nationals I saw were the dock workers. They were much shorter than those of us on the ship. They looked even tinier from the aircraft carrier's flight deck as they scurried about securing our ship to the pier. When I got off the carrier, I was met by a member of the Shore Patrol (SP). He transported me by jeep to the train station. He handed me my orders and tickets for the train and ferry, instructing me not to get off of the train until it got to Sasebo. The Sasebo train station was directly across the ferry terminal.

On the train I observed the Japanese passengers. I knew no Japanese and I heard no English, so we did not communicate. The thing that impressed me is that they all seemed so polite, speaking quietly. The women covered their mouth when speaking. The children were exceptionally well behaved. There was no screaming, yelling, or running. We stopped at a station where some Americans boarded the train. It was very obvious that they had been drinking. They were very loud and demonstrative, and they were extremely rude. I was embarrassed to see such rudeness. I saw a lot of the country on the train ride. We passed mostly small villages and what I think were rice fields. We arrived at Sasebo the following day in the evening. I could see the ferry from the train station.

I boarded the Japanese ferry, the Kongo Maru, for an overnight trip to Pusan, Korea. The sea between Sasebo and Pusan is named the Straits of Tsushima. I was the only American sailor aboard. The compartment in which we slept was wall to wall mat. The five other passengers and I slept on the mat-covered floor with a single blanket and a small pillow provided by a crew member. We arrived in Pusan early the following morning. The USS Haven, with its white body, three red crosses, and a green stripe between the three crosses, was tied up at a pier. Its top deck was also painted white with at least one cross.

Pusan was a city teeming with human life. There were literally thousands of people wandering the streets. Most seemed in need of a bath and clean clothes. I found out that most of them were refugees who had escaped the war further north.

I reported for duty aboard the USS Haven, and was immediately assigned to the surgery department as a surgeon's assistant, even though I had no training or previous experience. As far as I can remember, all the corpsmen lived in one compartment. I knew no crew members, nor do I ever remember seeing the ship's captain. The mess hall compartment was large, and it accommodated all the enlisted men. The officers and chiefs had their own dining areas. I was impressed with how clean all areas of the ship were kept. We could accommodate up to 800 patients. I never knew how many wards there were aboard. I know that the wards were above the surgery department.

When I first arrived aboard the Haven, casualties were being received. The operations went around the clock until the last and least serious were taken care of. I certainly didn't think that anything about the ship was inadequate. The surgeons were top notch, and the nurses and corpsmen were very dedicated. The ship operated just like a stateside hospital, with all the necessary facilities. There were about a hundred and twenty corpsmen or more. We had every department any hospital would have. I have no idea how many doctors and nurses were aboard. In surgery we had an average of six surgeons, four anesthesiologists, one female nurse, and up to six corpsmen. When I first went aboard the Haven, the department was shorthanded. The corpsmen I remember were Donald Bowles from Washington State, Ted Wilkin from Colorado, Don Baker from Pennsylvania, and T.J. Wilkes from Georgia.

On one occasion, I was able to have a few hours leave off the ship and meet the family of a fellow student who I had met at Menlo College. He told me that his family lived in Inchon. I found his family by going to an elementary school and inquiring about the Choi family. I didn't expect to find them, but it was my good fortune that the school had a teacher of English who told me that William Choi's sister attended that very school. Choi's sister was excused to take me to meet her family. The father spoke English very well. He was happy to know that his son had made my acquaintance. I also got to get off the ship for a few hours on shore leave when we went back to Japan to take our patients to the Naval Hospital. While there I visited Tokyo, taking the train from Yokosuka. Four of us, all corpsmen, went on R&R for one week to a military run hotel at the base of Mount Fuji. We four occupied one room. We walked up to the base of Mount Fuju. We had no desire to go any further. We rented a row boat and spent a couple hours at a nearby lake. The service by the hotel personnel was excellent. Our waiter remembered everything we ordered and who ordered what without writing it down. All of it was provided without charge.

We had elective surgeries on the hospital ship. There were hemorrhoidectomies, nerve repair, appendectomies, and at least one mastectomy, among other minor corrective surgeries. I did not have specific hours of duty. We were to be available twenty-four hours a day. We usually knew in advance when we would be receiving casualties. My first job was assigned to me by the department head nurse. When she found out that I had no previous surgical room experience, she assigned me to washing instruments. As the instruments were brought to me in the back room directly from the operating rooms, I washed each and every instrument with green antiseptic liquid soap. I used a small bristled brush to clean them. I was to try to memorize each instrument's name by looking at a chart the nurse had posted on the bulkhead. After thoroughly washing each instrument, I repacked them as a kit, and sterilized the kit in an autoclave for no less than half an hour.

As mentioned earlier, prior to arriving at Pusan, I hadn't had any experience with patients who were victims of war. Back in the States, when I was working at Oak Knoll Hospital, I had the opportunity to visit with patients who had been casualties. The patients at Oak Knoll were all on their way to recovery. It was a far different story in the hospital ship. They were new casualties who needed immediate attention or they could die. When I first was pressed into assisting an orthopedic surgeon with an amputation of a patient's right arm at the elbow, I explained to the surgeon that I had no experience. He answered that it didn't matter, since all he wanted me to do was to hold on to the arm so that when he completed the amputation it would not fall to the floor. I initially gagged and almost vomited. The surgeon was very understanding, and advised me to breath through my mouth. He had a calming effect on me. I wrapped up the end of the patient's severed arm and carried it down to the morgue. That was my introduction to surgical procedures. I don't remember the name of the doctor whom I assisted in the amputation, nor do I remember the name of any of the doctors I assisted. Maybe I could if someone who happened to work in the same department would jog my memory. It is very difficult after 50 years to remember specific names or dates.

I continued working with that doctor until I learned the instruments and procedures to his satisfaction. It seemed like weeks, but I believe I only worked with him for about one week. That was actually a long time since we worked on quite a few cases during that week. I did not feel adequately trained when I first assisted in surgery, but confidence came with time and experience. At first, I did not know the instrument the surgeon needed as he proceeded in the operation. He would put out his hand while he held his concentration on the surgery site. I was supposed to anticipate his need and hand him the appropriate instrument.

The head nurse, who was a trained operating room nurse, helped me by advising before, during, and after each operation. I began to feel that I knew what to do. As I gained more experience, I knew when to hand him clamps to stop the bleeding, suction as needed, scalpel and various other instruments. In every operation there were specific steps or procedures from the beginning to the closure of the wound. I had to know the type of sutures that would be needed to close the wounds. I had to count all the instruments at the end of the operation, and inform the surgeon that all of them were accounted for. The surgeons relied on the corpsman to know what was needed as the operation progressed, so that he would not need to look on my tray and pick up any instrument. If the corpsman handed him the wrong instrument, the surgeon put that instrument down and put out his hand again.

When I finally felt very sure of myself in orthopedic surgery, the nurse assigned me to abdominal and chest surgery operating room. Finally, she assigned me to neurosurgery, where we operated on head and spinal injuries. When I was transferred from one surgery to another, she explained the reason for it and I accepted it willingly. She told me that I was the newest corpsman in surgery, and I would be the last to be transferred off the ship. She wanted me to be well-trained when the time came that the others would leave and I would remain. There were some surgeons who refused to work with a corpsman who was not properly trained. I was lucky never to be rejected by any surgeon. I did prefer the orthopedic surgeon because of his demeanor. Nothing seemed to shake him up. The neurosurgeons, on the other hand, were very temperamental.

At about this point, we got word that the USS Haven was due to rotate back to the United States, and that the USS Consolation would soon arrive to take the Haven's place in the Pusan harbor I was elated because my wife and I had been married just ten days before I was shipped out to Korea. I wanted to go home to be with her. As it turned out, the Haven left Korea when the Consolation arrived. From what I understood, the medical personnel aboard the Haven had already served their tour of duty, which was around nine months. They were all due to rotate back to stateside. I had only one month's duty on the Haven (although it seemed like an eternity), so I was transferred to the Consolation.

I discovered that I was not the only one transferred from the Haven to the Consolation. There were at least ten other corpsmen, one of which was Ted Wilkin. He told me that the group was in Yokosuka, Japan, on the Haven when they got the word. They took the train ride to Sasebo and then the ferry back to Pusan. I was transferred while both ships were along side in Pusan.

My first month aboard a hospital ship had been a busy one, and the months that followed on the Consolation proved to be equally so. During times of heavy influx of patients, I felt I was well-prepared to handle the pressures and needs at hand. I had excellent training aboard the Haven, thanks to the nurse who helped train me and the surgeons who had patience with me. Unfortunately, I don't remember any of their names.

I was transferred to the Consolation on October 16, 1951, and I spent the next two years aboard her, primarily in surgery. I assisted in all surgery rooms as needed. As the surgeon's assistant, I prepped the patients, set up the instrument table with all necessary instruments, and when the operation began, handed the correct instrument to the surgeon. After the operation, I cleaned and prepared the room for the next patient. Sometimes we had very little time to clean up between those incoming patients.

The only difference between the Consolation and the Haven was that the Consolation had a helicopter pad on its top deck and the Haven didn't. It had a red cross on the helicopter landing platform. The ship was lit up at night so we wouldn't be mistaken for a war ship. The main mast was lit up like a red cross. I don't know the length or width of the hospital ship. I can only say that it was bigger than a destroyer.

Shortly after it arrived in the Pusan harbor, the Consolation sailed on to Inchon. As I understood it, the Allies had retaken the city of Seoul and the war was now further north, so the Consolation was ordered to Inchon Harbor, which was just south of the capital. It would take a lot less time to receive casualties at Inchon than if the Consolation was anchored further south at Pusan. It was around November that the move was made to Inchon. I never did meet with William Choi again. I tried contacting his sponsors, who once lived near San Jose, but was unable to locate them.

We knew in advance that we would be receiving casualties because the field headquarters sent a message to our radio room. Our radioman then relayed the message to the officer of the deck. He informed our chief of surgery. Those of us in surgery were then notified to be prepared to receive casualties.

Casualties were brought to the Consolation by helicopter and landing craft. As casualties arrived by whichever transport, a doctor would be on deck to check each patient. He then directed the corpsmen to take the patient to the necessary department. Most of them went directly to surgery. A few less serious ones went to X-ray or some other department. In two of the photos in the slide show in my memoir, you can see the doctor talking to the pilot or waiting for the corpsmen to carry the patients to him. There were many times that we had high influx of casualties during my tour of duty aboard the ship. Most of them were because an offensive battle by one side or the other. The Consolation was in Korea during the major battles. I was aboard during four of them. Besides these major battles, there were many other smaller in number attacks by both sides. As far as I was concerned, every time we received a high influx of casualties, I considered it to be a "major battle." And it happened too often.

During the high influx of casualties, we operated on casualties up to four days straight. We handled all types of wounds. The most serious were operated on first. During the winter we had terrible frost bite casualties (feet and hands). Most of the injuries were caused by shrapnel in the brain, thorax, and abdominal areas. We had injuries in the extremities caused by land mines or hand grenades. We also had several patients who were treated for something other than war-related wounds. One that I remember was a high-ranking officer who had fallen and had a ruptured bladder. We repaired it.

Once we had a fully-armed Turkish soldier show up at our ship. We had no idea what was wrong with him. No one spoke his language. He stayed with us for a week. The lab ran a series of tests on him, and could not find any physical or medical problems. We all think he was ready for a short vacation and he took the opportunity to stay with us in a safe and clean environment. We heard that the Turks were ferocious fighters, and often used their swords in close hand to hand combat.

We cared for each and every one of our patients, but we also had some "special" ones, too. Most of us took particular interest in the Korean children patients. We tried extra hard to make their stay a pleasant one. Some of the children we took care of had spinal meningitis. There was not much we could do for them. A celebrity patient who was discharged from the hospital ship was the baseball player Ted Williams. When he was admitted as a patient, many of us went up to see him.

There were so many casualties, it is difficult for me to just remember "a few." The list would go on and on. So many of them still are in my memory. Some had horrific injuries so life-threatening that I felt they would never recover from them. I remember the patient who lost both arms and legs right at the torso. When I went to see him in the ward, he begged me to end his life. I also remember the patient who lost the top of his cranium. His brain was still intact, but he only lived a week. I remember the doctor who was hit by the helicopter blade as he approached to check on a casualty. I can understand why some medical personnel developed some emotional problems with regard to the patients. It goes without saying that we did have a number of medical personnel who developed emotional difficulties. One corpsman in our compartment attempted to hang himself with a belt from the top bunk. A couple of us were able to get him down before he succeeded. He ended up in the psychiatric ward. Others I heard about actually sought psychiatric help.

The surgeons took heroic measures to save the patients, such as administering epinephrine and massaging the heart. It was hard for me to lose a patient who was seriously injured. I, for one, would think, "Here's someone's son, husband, or father who has been seriously injured, and probably will never be the same again. I not only felt badly for the patient, but I also felt badly for his family. Still, my job assignment was satisfying for me. I felt that I was doing a very important job, and as well as I could, I knew that I had helped with the saving of lives. My worst memory of serving on the Consolation was when we operated on casualties who had no chance of survival. We continued working on them until there was absolutely no hope.

The one thing that occurred which has personally haunted me all these years was when one of the corpsmen in our department volunteered for front line Marine Corps duty. He was back aboard our ship within a week as a casualty. It was an emotionally devastating experience for me to see one of ours in the condition he was in. I did not participate in his surgery, but as far as I know, he survived his injuries. His name was Bowes and we kept repeating his name as we were treating him. He lost his left eye and several fingers in his left hand, and he had shrapnel all over his body. He was not aware of his injuries at the time because he was unconscious and barely alive. After his operation, I could not bear going to see him in the ward.

I never did go exploring on either the Haven or the Consolation, but they were very similar in layout. I don't know how many wards the ships had, but the two hospital ships each handled approximately 900 patients at a time. There were at least two full decks of wards, probably more to be able to handle that many patients. I believe there were six levels, but I am just guessing about that. I am not sure. I know that on the level where surgery was located, there was also a lab, optical services, dental, X-ray, physical therapy, and other such medical departments. In surgery, we had three operating rooms--one for orthopedic, another for thoracic and abdominal surgery, and the third for neurosurgery. Each room had the instruments necessary for each particular surgery. But, when necessity arose, any of the rooms could be used for whatever surgery was being performed.

The living quarters for enlisted personnel were aft and three or four decks down. All the living quarters where I slept were for corpsmen, I think. The area for both female and male officers was on the forward part of the ship, but I am not sure on which deck. I know it was the officers' living quarters because we were not allowed beyond that point. There was a lobby-like compartment in which there were doors that led to the officers' quarters. The living quarters for the corpsmen aboard the hospital ship were no different from aboard any other Navy ship I had been on, except that our compartment was painted white instead of gray as on other ships. I was not aware of any problems from male/female personnel aboard.

Although we were on call 24 hours a day, on days of light duty, I had a certain amount of leisure time. When we had no patients to operate on, I had enough free time to sightsee in and around Inchon. I got to see a lot of the city. I took my Argus C-3 camera and took photos of the Korean people, the boats (San Pans), and buildings. The Consolation also went to the port of Sokcho-Ri near the 38th parallel, and I took some pictures there.

During moments of limited leisure aboard ship, first and foremost I used the time to write to my wife. I studied the corpsman's manual and surgical manuals that the nurse assigned for me to study. During good weather, when I was required to stay aboard the ship, I went to the top deck to get some sun. Because we spent most of our time down below, most of us got pretty pale.

During one of my times off, I walked past a room that a crew hand was cleaning. Because the door was open, I accidentally discovered that the Consolation had a darkroom. That happened toward the end of 1952 or early 1953. The crew hand allowed me to inspect the room while he was cleaning it, but not after he was finished. I discovered that there was lots of photographic equipment aboard the ship, but I was never allowed personal access to it. Near the end of my tour of duty on the Consolation I was ready for a transfer out of surgery, so I requested a transfer to be the official ship's photographer. I sincerely thought that the ship could use a photographer. Also, at that point in time we received a number of newly-trained surgeon's assistants. In my opinion we were overstaffed. That's the reason why I felt I was ready for a change.

I felt that my request must have been misunderstood or completely ignored, because I was transferred to the X-ray department as an X-ray technician. The radiologist explained that this was as close as I would get to photography. I made the best of it and took the new assignment in stride. My job was to take X-rays of all parts of the body as requested by the doctors. I was trained by the head tech, who explained to me that X-ray was not much different than taking photographs. The same principle was involved. We had to be aware of the different densities of the body parts and adjust exposure accordingly. I also developed the film myself. The X-ray department had three rooms and a portable X-ray machine that could be taken to any ward as needed.

Within a short time I felt I was as good in X-ray technique as the rest of the technicians, with the exception of the master technician who taught me the ropes. It was easy, enjoyable, and a lot more pleasant than the operating room. I did not have to worry about sterile technique, but I did have to worry about overexposure to X-rays. We wore badges which monitored when we were getting overexposed. The badges we wore were a one inch by one inch pin with a film that measured exposure. The radiologist periodically asked us for the badge so he could check it. I was never told that I had been overexposed, nor had anyone else that I can recall. An added plus to this new assignment was that I got to use the room that was used for developing the X-ray films as my personal darkroom. I developed rolls of black and white film in the dark room using the same chemicals that we used for X-ray film. We had a discarded enlarger and a contact printer.

Politicians and other important people visited the Haven while I was aboard, and so did reporters. I don't remember the names of any of them. I was interviewed by one of those reporters about our work aboard the ship, but I never did see a published article of my interview with the reporter. At Pusan, the ship was tied to the pier. In Inchon we were anchored about five miles away from the Inchon bay. Four other fellow sailors and I visited the capital of South Korea on one occasion. We took an army bus to the capitol. We visited both the Emperor and Empress's palace grounds, as well as the capitol and the train station built by the Japanese during the first World War. Every place was nearly deserted. No one at any time tried to stop us or question us. We came across some armed Army patrols who were surprised to see sailors that far inland. Of course, I took photos of Seoul.

Our ship was not supposed to be in harm's way, however, we did have an enemy plane fly over our ship on more than one occasion. The pilot was clearly visual.

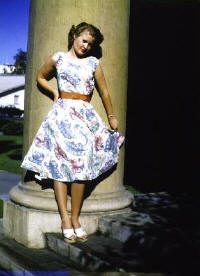

During my time on the hospital ship, I was receiving mail almost on a daily basis, primarily from my wife. Besides writing to me, she sent me goodies such as cookies, beef sticks, and candy. She also sent recordings of her voice. One of her distant cousins was in the recording business, so he helped her record messages from home. She just talked to me. She told me how much she missed me, that she loved me, and that she could hardly wait until the ship returned to the United States. Her cousin The distant cousin's voice preceded her voice by introducing himself and explaining how the recording was made. On one occasion my wife also sent me a stuffed rabbit, which I took to the Catholic nun's orphanage and gave to one of the orphans. I never did ask for anything in particular. Other than via mail and the records of her voice that she sent me, I had no other contact with my wife, either aboard the Haven or the Consolation. She sent a picture of herself which I taped to my locker door. Her photo helped me get through all those months aboard the hospital ships.

I spent all the year's holidays aboard the Consolation. Except for the religious services, there were no celebrations of any kind with one exception--a special menu that day. The cook and baker prepared what I considered to be excellent meals in keeping with the holiday. Our baker especially baked delicious cinnamon rolls. I couldn't get enough of them. In the X-ray department, we had a skeleton that we used to pinpoint areas that we needed to locate for X-ray purposes. At Christmas, we decorated up the skeleton like a Christmas tree.

Occasionally, entertainers performed on the Consolation to break the daily routine. Debbie Reynolds and her troupe came aboard, but I only watched a small portion of it since I had duty that day. I could not stay to see it all. We also had Korean groups wearing colorful costumes perform for us. I became very close friends with T.J. Wilkes who was a dental assistant on the Consolation. He was easy to communicate with and we seemed to have the same interests. I just recently found out that he has died.

The best memory I have of serving on the USS Consolation was when we got a chance to visit Tokyo and other important cities in Japan. The hardest thing for me was having a patient die, when the surgeons tried heroic efforts to save him.

While I was aboard the Haven I did not have the opportunity to meet any medical personnel on any other ship. But when I was transferred to the Consolation and we went to Inchon, there was another hospital ship there already. The ship was a converted yacht from Denmark, and it was called the Jutlandia. It had carpeting throughout and mahogany paneled walls. It accommodated about half as many patients as the Consolation. The patients' beds in the wards were built so that the beds stayed stationary even in rough waters. All the crew and medical personnel were civilians.

I went aboard as soon as I was able, stating that I wanted to meet the medical personnel. But actually, the true reason for going aboard was to have the excellent hot chocolate and Danish pastries. I did meet the Danish staff, but I also met two American Navy corpsmen who were assigned to the ship. What nice duty, I thought. They got to go to Denmark when the ship went back.

We all knew that the Consolation was to return stateside around nine months after it arrived in Korea. Either the Haven or the Repose was to replace us. I never did see either one arrive. We just left Inchon, sailed to Japan, and unloaded our patients at Yokosuka's Naval hospital. I am not sure if we kept any patients aboard on our return back to California. It took about two weeks to get back after leaving Japan.

My wife did not know when or where the ship would arrive, and I had no way of communicating with her except by letter. My letters usually took about two weeks to get to her. We arrived in San Diego and I hitchhiked to Los Angeles. The driver took me right to my wife's front door. Billie then took a vacation from work when I got home. I am not sure about the time frame, but our time together was very short. I was to return to the ship within four weeks or less.

The Consolation then went back to Korea, stopping in Hawaii for two days. When we got back to Inchon, there was no other hospital ship there except for the Jutlandia. I knew I was there for at least another nine months. I was still aboard the Consolation when a truce was declared. We were all very elated. We heard that the prisoners of war would be exchanged at Panmunjom, near the demilitarized zone. I am not sure of the date, but I do know that it was getting near to the end of my enlistment.

I missed my wife immensely, and I knew that we would not be receiving any more casualties, so in 1953 I made a formal written request for a transfer to any west coast naval base. I had served two tours of duty in Korea. The reason I gave for my transfer request was that I planned to continue with my college education and I needed the time stateside to complete all the necessary paperwork and the leg work that went with the preparation of being accepted to the college of my choice. I had about four or five months before my discharge. My request was approved. I was to wait until the troop ship Marine Serpent arrived in Inchon. I informed all the people still in the X-ray department that I was going home soon. On the last day aboard the hospital ship, I packed my sea bag, said my goodbyes, and boarded the Marine Serpent headed back to Seattle, Washington. I forgot a ton of exposed film and slides which I kept in a slot in the back of my locker, but I was glad to leave, primarily because I would get to see my wife again sooner than I thought.

I was transferred from the Consolation on July 30, 1953. I was the only one from the Consolation aboard the Marine Serpent, so I didn't know anybody on that ship. I had over five months left in my enlistment. When I left the Consolation I was a third class petty officer. Aboard the Marine Serpent, I took the test for second class petty officer and passed it.

The Marine Serpent was manned by a civilian crew, with the exception of the sick bay. We had a Navy doctor and three hospital corpsmen. I soon found out that I had been assigned to the Marine Serpent, rather than to a west coast Naval base. My wife had already quit her job at the hospital in Los Angeles and had moved to San Jose. She stayed at my parents' home, thinking I would be assigned to a base near my hometown.

On the way to Seattle, we came across some very rough weather. I thought the ship was going to split in half. It was even worse at night. I strapped myself to my bunk and was prepared to make a dash to the upper decks and to a life boat if it became necessary. Fortunately, we made it through the rough weather, which lasted for a couple of days. With no stopovers, we still made it to Seattle in about two weeks.

When we arrived in Seattle, we were told that we had a one week layover, and that we would be going to San Diego after that week to pick up Marines to transport them to Inchon, Korea. One of the corpsmen aboard the Marine Serpent had his car on base in Seattle, and he wanted to drive to Los Angeles. He offered me a ride to San Jose if I would drive to San Jose while he slept. I took him up on it. We left in the evening, arriving in San Jose early the next morning. My wife was surprised to see me, and we enjoyed our week together. I planned to take a Navy flight from Moffet Naval Air station back to a base near Seattle, but instead I ended up having to take a Greyhound bus back to the base.

We left for San Diego, picked up three thousand Marines, and headed back to Inchon, Korea. When we crossed the International Date Line, ceremonies were held. I took lots of photos. The Marines were pretty rough on the new inductees. The trip back to Korea was also rough sailing. We had a lot of seasick Marines. The Marines traveled with full battle gear, and as a result, we had one bayonet stabbing. The doctor was not a surgeon, and I was the only experienced operation technician, but we were able to patch him up and he survived. The other Marine spent the rest of the trip in the brig. When we arrived in Inchon harbor, there was the Consolation. We unloaded the Marines on to floating platforms, and then onto LSTs. The LSTs took them ashore.

I made two trips on the Marine Serpent. The first trip we transported Marines to Inchon. The second trip we transported Army troops to Pusan. On the trip back from Korea, we had only one patient--an army captain who came down ill and was admitted to sick bay. He had contracted a disease while stationed in Korea, so I spent long hours caring for him. He died before we got back to the United States. Only after his body had been taken off the ship did I wish I had written down his name and address. I felt that I would have liked to talk to his family about his last days. He talked to me about his family and his hopes for the future. I really don't know if I would have been able to talk to any of his family, though. I probably would not have used the proper words.

When we returned to Seattle, I requested my overdue thirty-day leave. It was approved. My wife quit her job as a library clerk in San Jose. She took the Greyhound bus to Seattle, and we rented an apartment for those thirty days. My wife was planning to stay in Seattle since it was my ship's home base. We visited all the places of interest while there. At the end of my thirty day leave, I reported back to the base. The Marine Serpent had already left for another trip to Korea, so I was reassigned to another troop ship, the USS Buckner.

The Buckner was a larger ship which transported not only troops, but dependents of overseas military personnel, as well as some dignitaries. It was more like a cruise ship. I really enjoyed being on it. The only thing lacking was a swimming pool. Its home port was San Francisco. In sick bay we had three corpsmen, one nurse and a doctor. I was the ranking corpsman, so I was in charge of sick call and typing up all the medical reports. For the first time I did not have to stand in line for my meals. We were served and we ordered from a menu. The staff had their own movie room with the latest releases. We picked up passengers in San Francisco and Pearl Harbor and transported them to Yokohama, Japan. My wife would meet the ship when we came in to San Francisco. I made only two round trips on the Buckner. On one of those return trips, I was met by two recruiters who made me a deal they thought I couldn't pass up. They wanted me to reenlist for one thousand dollars, and I would be sent to New York for specialized training so that I could serve aboard a submarine. I would be the MEDIC on the boat. I refused their offer.

In August of 1954, I was transferred to Treasure Island naval base for early discharge on August 23, 1954. With three hundred dollars in cash, I was finally out of the Navy. I took the Greyhound bus to San Jose, and resumed married life with Billie, who had already gotten a job as a nursing assistant at the San Jose hospital. I was home barely a week when I went to the fruit cannery where I had worked when I joined the Navy and asked to be rehired. I got on the very same day, doing the very same work I had done previously. We lived with my parents for about a month, when we were able to rent an entire upper flat next to my parents' home.

I decided to stay at the cannery until the end of the season and then request a permanent job with the company in the company warehouse. I talked to a couple of high school friends who were year-round employees. They encouraged me to apply for permanent employment. I was turned down because I had no seasonal seniority. I was laid off at the end of September. I immediately applied for a job at County Hospital. I was hired the very first week as an orderly. I worked in the men's terminal cancer ward. It was unpleasant work because somebody died almost every week. After a couple of months, I asked for a transfer to ER. I got my transfer, but it was not much better there. I decided to continue my schooling the following semester, which would be in September of 1955. I spoke to a couple of ex-Navy corpsmen who had opened their own rehabilitation center after working at the county hospital for a couple of years. I was encouraged.

I applied for admission to the University of California at Berkeley, and I was accepted. While at Cal, I got a job in the campus hospital. My wife got a job with Blue Cross Insurance in Oakland. We lived in the student housing while I continued my formal education. I graduated with a B.A. in liberal arts. After my final year at Cal, I had planned to transfer to San Francisco School of Medicine for my final training as a physical therapist. The nurse at the campus hospital made a suggestion. Violet Auger, the head of the campus hospital, suggested I look into teaching. She advised me to talk to the Dean of Education. She was aware that my wife and I were expecting our first child. We would need a steady income soon rather than later. The Dean advised me to try teaching for one year. If I did not like it, I could go back to training as a physical therapist. I earned my teaching credential through San Jose State College, and the Dean placed me in a rural school.

The school was located about a hundred miles north of San Francisco. I was employed to teach a 7th and 8th grade combined class, teaching all classes except music and art. The students were the children of farmers, Pomo Indians, and migrant workers. I was helped by a teacher supervisor who dropped in to observe me and give me helpful pointers. Right before the second school year began, the high school discovered that I spoke Spanish. No foreign language was offered at the high school at that time. My supervisor made arrangements with my principal for me to teach one class of Spanish at the high school. He wanted his brightest students to qualify for admission to a university, and a foreign language was a requirement. During the summer break I attended the University of Guadalajara in Mexico in order to qualify for the Spanish credential. The following year, I applied for a teaching position in San Jose. I was hired at my first interview as a Spanish teacher.

The name of the school in which I was offered employment was named Castro Junior High. The principal was Frank Lovoi. In one of my first Spanish classes, I discovered that one of my students had been born at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital. She was born during the months I was stationed there. During "back to school night", I spoke to her mother. She said she had a photo of her baby (Dana Mcafee) and the corpsman who took care of her. The corpsman was me. I had the exact same photo. What a small world! I did two more years of post graduate work in education, and remained a schoolteacher for 32 years, retiring in 1990. After I retired, I substituted for five more years.

The name of the school in which I was offered employment was named Castro Junior High. The principal was Frank Lovoi. In one of my first Spanish classes, I discovered that one of my students had been born at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital. She was born during the months I was stationed there. During "back to school night", I spoke to her mother. She said she had a photo of her baby (Dana Mcafee) and the corpsman who took care of her. The corpsman was me. I had the exact same photo. What a small world! I did two more years of post graduate work in education, and remained a schoolteacher for 32 years, retiring in 1990. After I retired, I substituted for five more years.

My wife and I had three boys. My Navy training came in handy when our first son was born. Billie came down with a severe case of the Asian flu a few days after his birth. I took over his complete care until Billie got better. David, who was 42 in October (2002) and is pictured at right, is our eldest son. Our next boy Edward died at age 15. He came down with a fatal illness the last day of school before summer vacation, and died the first week of September. My wife and I, as well as our remaining two sons, were emotionally devastated. We had emotional support from the staffs of both my school and the school he was attending. We were thankful for all the support we got from everyone. Our youngest son was born on my birthday. We named him Anthony. He was 37 last December (2002).

Now both fully retired, my wife and I go on vacations, mostly in the United States.

While going to college and for many years thereafter, I did not have occasion to discuss my experiences in Korea, so I really do not know if the other students' outlook on life was any different from mine at the time. At Cal I was in the upper division, and I associated mainly with graduate studies students. Their main concern was completing whatever project they were on. My concern was to get my degree and get a job.

I know that going to Korea did change me. Life became very precious to me, and I did not take any unnecessary risks. I found out how short life can be. I changed my mind about going to war without a just cause. In my opinion, the United States and the rest of the countries involved in the war were justified in preventing North Korea from invading South Korea. The South Koreans greatly appreciated our help and demonstrated it on our revisit to Korea. I understand that Truman did not want to expand the war beyond the 38th parallel. Since he was the Commander-in-Chief, his orders had to be obeyed. The Korean conflict was not a declared war, but a police action. I understand that the United Nations was attempting to get North Korea to the bargaining table from the onset of the war. That was finally accomplished with the treaty at Panmunjom, but after thousands of lives had been lost.

While I was working for my teaching credential, one of our professors predicted the next war that the United States was going to be involved in would be in a country named Vietnam. The US was already spending huge amounts of money in that country several years before the war. Again, what was accomplished there?

I revisited Korea when the Korean War Veterans Association offered a revisit trip to American Korean War veterans. My wife and I took the trip and we were treated royally. We received the best accommodations with meal buffets, as well as visits to Seoul, military installations, and war memorials. I was impressed with how modern the country now was. The traffic was just as bad as ours. I showed my slides to a Korean army general who was interested in seeing them. He said that it was before his time, and that they no longer had villages, but modern cities instead.

The good I see coming out of the Korean War is that, with our help, South Korea is now an economically prospering country. As I understand it, North Korea is not. Even though I think we should not have troops stationed there, I can appreciate the fact that our troops act as a deterrent to any further military action by the North. But we were warned that it could happen at any time.

The Korean War carries the nickname, "The Forgotten War" because very few people even knew where Korea was. Again, it was not a declared war, but a police action. As far as most people knew, we sent military advisors to aid South Korea in their war against the communist North Korea. At least two of my family members did not even know that I was in Korea.

If some student someday finds a copy of this interview for use in a term paper, I hope they will understand that my time in the Korean War was an invaluable experience. I matured very fast. I learned how precious human life is. My heart went out to the innumerable casualties we cared for aboard ship. I agree that World War II veterans are treated with more respect and appreciation than Korean War veterans for the simple reason that that war was in defense of an attack on our soil. There was a lot of patriotism on the part of most Americans when that happened. The Korean War, however, was not a declared war, but a police action. This country had not been attacked. I personally feel that those who enlisted in the services did not do it out of patriotism. When I went to the Marine Corps base early in my enlistment, what I heard from the new recruits was that, "We are going to Korea to kick ass." That is the same thing that I am hearing from some youngsters these days about going to Iraq.

I was never resentful that I was sent to Korea. I felt that I had been, in a small way, of some help in that war. As I have written previously, having served as a Navy corpsman made me more aware of how precious life is. After the Navy, when I worked in the emergency room of the county hospital and we received some DOA teenagers, I felt it even more. The teenagers had been drinking and driving when they were involved in a head-on accident. My thoughts were, "What a waste of precious life. They had a whole life ahead of them." They killed themselves with the decision they made to drink and drive.

For all these years I wondered whether the ship was having any reunions. I searched the newspapers and the American Legion magazine, but never found anything--not until my older son was visiting us once. I happened to mention to him about my search for a Consolation reunion. He got on the computer and within minutes he found that the Consolation had already had eight reunions. Just that past month they had held one on the Queen Mary at Long Beach. He got me the address of the reunion contact. I was disappointed to say the least that I had just missed the reunion. He contacted the committee chairman and found out that the next reunion would be in Minnesota in two years. My wife and I planned to go to that reunion but were unable to go because of a conflict. I talked to the Consolation reunion chairman to let him know I had a number of slides and photos.

I attended my first Consolation reunion in 2004 in Virginia Beach. I was pleased to meet one of the corpsmen with whom I worked in the X-ray department. It was his first reunion, also. His name is Donald Baker. He did not remember me until I showed him a photo of us on the main deck catching some sun rays. I also had another photo of him in the dark room, processing some X-ray films. I asked him about the corpsman who had volunteered for the fleet marine force and had come back as a casualty, but he did not remember his name either. The radiologist with whom we worked was Dr. Gleason. My son David made some 8x10 enlargements from my slides to show those in attendance. My photos were a big hit. They were especially of interest to the main speaker at our reunion, Jan K. Herman. He has written several books on Navy medical history and is the editor of a navy medical publication. I also got to talk to other corpsmen whose photos I had taken, and I met the person who replaced me when I left the ship. The next reunion will be in Las Vegas in 2006, and I plan to attend.

At times this interview has been difficult for me. I have for all these years repressed the images in my mind of most of the horrific injuries that we in surgery worked on. I felt so glad that I was safe and sound aboard a clean ship, and not exposed to the conditions that our troops had to contend with. I felt guilt, at times, that I had no desire to volunteer for Marine Corps duty when the request for platoon corpsmen was received.

I'm very thankful to Lynnita Brown for helping me share my experiences. It has given me a sense of closure. I will carry those images and feelings for the rest of my life.